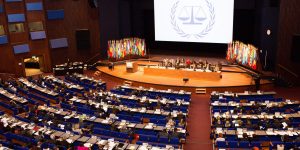

The Assembly of States Parties (“the Assembly”) is the Court’s management oversight and legislative body and is composed of representatives of the States which have ratified or acceded to the Rome Statute.

In accordance with article 112 of the Rome Statute, the Assembly of States Parties meets at the seat of Court in The Hague or at the United Nations Headquarters in New York once a year and, when circumstances so require, may hold special sessions.

Each State Party has one representative in the Assembly who may be accompanied by alternatives and advisers. The Rome Statute further provides that each State Party has one vote, although every effort shall be made to reach decisions by consensus. States that are not party to the Rome Statute may take part in the work of the Assembly as observers, without the right to vote. The President, the Prosecutor and the Registrar or their representatives may also participate, as appropriate, in the meetings of the Assembly.

In accordance with article 112 of the Rome Statute, the Assembly is tasked with providing management oversight to the Presidency, the Prosecutor and the Registrar regarding administration of the Court. In addition, the Assembly adopts the Rules of Procedure and Evidence and the Elements of Crime.

At its annual sessions, the Assembly considers a number of issues, including the budget of the Court, the status of contributions and the audit reports. In addition, the Assembly considers the reports on the activities of the Bureau, the Court and the Board of Directors of the Trust Fund for Victims.

The Assembly is further tasked with election of, inter alia, the Judges, the Prosecutor and Deputy Prosecutors. The Assembly may also decide, by secret ballot, on the removal from office of a Judge, the Prosecutor or Deputy Prosecutors.

Structure

In June 2010, two amendments to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court were adopted by the Review Conference in Kampala, Uganda. The first amendment criminalizes the use of certain kinds of weapons in non-international conflicts whose use was already forbidden in international conflicts. It has been ratified by nine states parties and is in force in two of them. The second amendment specifies the crime of aggression. It has been ratified by seven states parties and is in force in one of them. However, per the language of the amendment, the Court will only have jurisdiction over the crime of aggression after two additional conditions are met:

(1) The amendment has entered into force for 30 states parties and

(2) On a date after 1 January 2017, the Assembly of States Parties has voted in favour of allowing the Court to have jurisdiction. The ICC is governed by an Assembly of States Parties. The Court consists of four main organs: the Presidency, the Judicial Divisions, the Office of the Prosecutor, and the Registry.

State parties

As of May 2013, 122 states are states parties to the Statute of the Court, including all of South America, nearly all of Europe, most of Oceania and roughly half the countries in Africa. A further 31 countries, including Russia, have signed but not ratified the Rome Statute. The law of treaties obliges these states to refrain from “acts which would defeat the object and purpose” of the treaty until they declare they do not intend to become a party to the treaty. Three of these states—Israel, Sudan and the United States—have informed the UN Secretary General that they no longer intend to become states parties and, as such, have no legal obligations arising from their former representatives’ signature of the Statute. 41 United Nations member states have neither signed nor ratified or acceded to the Rome Statute; some of them, including China and India, are critical of the Court. On 21 January 2009, the Palestinian National Authority formally accepted the jurisdiction of the Court. On 3 April 2012, the ICC Prosecutor declared himself unable to determine that Palestine is a “state” for the purposes of the Rome Statute and referred such decision to the United Nations. On 29 November 2012, the United Nations General Assembly voted in favour of recognizing Palestine as a non-member observer state.

Assembly of States Parties

The Court’s management oversight and legislative body, the Assembly of States Parties, consists of one representative from each state party. Each state party has one vote and “every effort” has to be made to reach decisions by consensus. If consensus cannot be reached, decisions are made by vote.[57] The Assembly is presided over by a president and two vice-presidents, who are elected by the members to three-year terms.

The Assembly meets in full session once a year in New York or The Hague, and may also hold special sessions where circumstances require. Sessions are open to observer states and non-governmental organizations.

The Assembly elects the judges and prosecutors, decides the Court’s budget, adopts important texts (such as the Rules of Procedure and Evidence, and provides management oversight to the other organs of the Court. Article 46 of the Rome Statute allows the Assembly to remove from office a judge or prosecutor who “is found to have committed serious misconduct or a serious breach of his or her duties” or “is unable to exercise the functions required by this Statute”.

The states parties cannot interfere with the judicial functions of the Court. Disputes concerning individual cases are settled by the Judicial Divisions.

In 2010, Kampala, Uganda hosted the Assembly’s Rome Statute Review Conference. In 2011, New York hosted the Assembly’s Rome Statute Review Conference.

Judicial Divisions

The Judicial Divisions consist of the 18 judges of the Court, organized into three chambers—the Pre-Trial Chamber, Trial Chamber and Appeals Chamber—which carry out the judicial functions of the Court. Judges are elected to the Court by the Assembly of States Parties. They serve nine-year terms and are not generally eligible for re-election. All judges must be nationals of states parties to the Rome Statute, and no two judges may be nationals of the same state. They must be “persons of high moral character, impartiality and integrity who possess the qualifications required in their respective States for appointment to the highest judicial offices”.

The Prosecutor or any person being investigated or prosecuted may request the disqualification of a judge from “any case in which his or her impartiality might reasonably be doubted on any ground”. Any request for the disqualification of a judge from a particular case is decided by an absolute majority of the other judges. A judge may be removed from office if he or she “is found to have committed serious misconduct or a serious breach of his or her duties” or is unable to exercise his or her functions. The removal of a judge requires both a two-thirds majority of the other judges and a two-thirds majority of the states parties.

Office of the Prosecutor

The Office of the Prosecutor is responsible for conducting investigations and prosecutions. It is headed by the Chief Prosecutor, who is assisted by one or more Deputy Prosecutors. The Rome Statute provides that the Office of the Prosecutor shall act independently; as such, no member of the Office may seek or act on instructions from any external source, such as states,international organisations, non-governmental organisations or individuals.

The Prosecutor may open an investigation under three circumstances:

- when a situation is referred to him or her by a state party;

- when a situation is referred to him or her by the United Nations Security Council, acting to address a threat to international peace and security;

- when the Pre-Trial Chamber authorises him or her to open an investigation on the basis of information received from other sources, such as individuals or non-governmental organizations.

Any person being investigated or prosecuted may request the disqualification of a prosecutor from any case “in which their impartiality might reasonably be doubted on any ground”. Requests for the disqualification of prosecutors are decided by the Appeals Chamber. A prosecutor may be removed from office by an absolute majority of the states parties if he or she “is found to have committed serious misconduct or a serious breach of his or her duties” or is unable to exercise his or her functions. However, critics of the Court argue that there are “insufficient checks and balances on the authority of the ICC prosecutor and judges” and “insufficient protection against politicized prosecutions or other abuses”. Henry Kissinger says the checks and balances are so weak that the prosecutor “has virtually unlimited discretion in practice”. Some efforts have been made to hold Kissinger himself responsible for perceived injustices of American foreign policy during his tenure in government.

As of 16 June 2012, the Prosecutor has been Fatou Bensouda of Gambia who had been elected as the new Prosecutor on 12 December 2011.[72] She has been elected for nine years. Her predecessor, Luis Moreno Ocampo of Argentina, had been in office from 2003 to 2012.

Registry

The Registry is responsible for the non-judicial aspects of the administration and servicing of the Court. This includes, among other things, “the administration of legal aid matters, court management, victims and witness’s matters, defense counsel, detention unit, and the traditional services provided by administrations in international organizations, such as finance, translation, building management, procurement and personnel”. The Registry is headed by the Registrar, who is elected by the judges to a five-year term. The current Registrar is Silvana Arbia, who was elected on 28 February 2008.

Headquarters, offices and detention unit

The official seat of the Court is in The Hague, Netherlands, but its proceedings may take place anywhere.

The Court is currently housed in interim premises on the eastern edge of The Hague. It intends to construct the ICC Permanent Premises in the Alexanderkazerne, to the north of The Hague. The land and financing for the new construction have been provided by the Netherlands and architects Schmidt hammer lessen have been retained to design the project.

The ICC also maintains a liaison office in New York and field offices in places where it conducts its activities. As of 18 October 2007, the Court had field offices in Kampala, Kinshasa, Bunia, Abéché and Bangui.

The ICC’s detention centre comprises twelve cells on the premises of the Scheveningen branch of the Haaglanden Penal Institution, The Hague. Suspects held by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia are held in the same prison and share some facilities, like the fitness room, but have no contact with suspects held by the ICC. The detention unit is close to the ICC’s future headquarters in the Alexanderkazerne.

As of July 2012, the detention Centre houses one person convicted by the court, Thomas Lubanga, and four suspects: Germain Katanga, Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui, Jean-Pierre Bemba and Laurent Gbagbo. Additionally, former Liberian President Charles Taylor is held there. Taylor was tried under the mandate and auspices of the Special Court for Sierra Leone, but his trial was held at the ICC’s facilities in The Hague because of political and security concerns about holding the trial in Freetown. On 26 April 2012, Taylor was convicted on eleven charges.

The ICC does not have its own witness protection program, but rather must rely on national programs to keep witnesses safe.