By Law Teacher

4.1.1 Assault, Battery and ABH – Introduction

Welcome to the fourth topic in this module guide – Non-Fatal Offences Against the Person! Non-Fatal Offences Against the Person encompass a range of offences where a person is caused some harm, but the harm does not result in death. There is a gradient scale of offences based on the level of harm caused to the victim and the level of intent demonstrated by the defendant. Each of these offences has their own actus reus and mens rea and are accompanied by charging guidelines as to the type of injuries they encompass. All of these elements must be considered when looking at a possible offence.

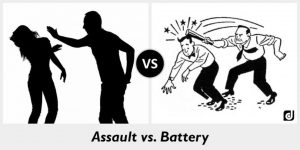

An assault occurs where someone intentionally or recklessly causes another person to apprehend (or fear) immediate unlawful violence. A battery occurs where a person intentionally or recklessly applies unlawful force. In legal terms, crimes will often involve an element of both assault and battery and the two are charged together as a common assault. Assault Occasioning Actual Bodily Harm (ABH) occurs where a person commits any hurt calculated to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim; such hurt need not be permanent, but must be more than transient and trifling. These offences are charged under section 39 Criminal Justice Act 1988 (common assault), and section 47 Offences against the Person Act 1861 (ABH) respectively.

Goals for this section:

- To understand the actus reus and mens rea components of assault, battery and assault occasioning actual bodily harm.

- To appreciate the charging and sentencing guidelines for each of the offences mentioned above.

Objectives for this section:

- To be able to identify the type and level of harm encompassed by assault, battery and assault occasioning actual bodily harm, which can be ascertained by referring to case studies in this field.

- To be able to analyse and evaluate the nuances of all the non-fatal offences, as required in an examination.

4.1.2 Assault, Battery and ABH Lecture

1.0 Common Assault

Common Assault is a common law offence and is not set out under any statue but charged under s.39 Criminal Justice Act 1988. It is used to refer to the individual offences of both assault and battery.

In legal terms, crimes will often involve an element of both assault and battery and the two are charged together as a common assault. For the purposes of exams however you will need to understand the constituent elements of and differentiate between both assault and battery.

1.1 Assault

As eluded to above the word assault is used interchangeably to refer to crimes of assault and battery, which are properly known as a common assault. In the present context the word assault refers to what is properly known as a technical assault. These are assaults where no physical contact occurs.

1.1.2 Actus Reus

The actus reus of assault is causing a person to apprehend the immediate application of unlawful force.

This can be broken down into two key parts:

- The defendant causes victim to apprehend the use of force against them, and;

- The victim apprehends that use of force will be immediate

(i) The defendant causes the victim to apprehend force.

The actus reus is established through the causing of the apprehension of force and there does not need to be any application of actual force on the victim.

It does not matter whether the actual application of force was even possible, as long as the apprehension is caused. To illustrate this, consider the following example. The defendant points an unloaded gun at a stranger in a street. There is no way he could shoot them even if that was his intention but the stranger will be unaware of this so will fear the application of force. Now consider that the defendant and his friend are shooting enthusiasts and are in a gun shop looking at unloaded display models. If the defendant picked up a gun and turned and pointed it at his friend and shouted ‘hands up or I’ll shoot’ the defendant’s friend will know that this is an empty threat and will not be caused to apprehend a use of force, thus no assault will occur.

R v Constanza [1997] Crim LR 576 states that words alone can cause the victim to apprehend harm and thus constitute an assault. For example, “I’m going to hit you” does not need to be accompanied by any action for an assault to occur. The ruling in R v Ireland [1997] 3 WLR 534 takes this further and states that silence can amount an assault. In this case the defendant made a series of silent phone calls to his victim causing them to fear immediate force and leading them to suffer severe psychological damage as a result of his on-going calls.

Just as words can cause an assault they can also prevent a potential assault from occurring. This point is demonstrated nicely in the case of Tuberville v Savage [1669] EWHC KB J25.

Just as words can negate an assault, the context and tone of such words can too negate an assault. In cases where menacing words were clearly intended as a joke and were taken as such there can be no assault. This is illustrated by the recent case of Chambers v DPP [2012] EWHC 2157 where the defendant took to Twitter to threaten blow up an airport after a delayed flight! It was clear to all that taken in context, despite the menacing nature of the words they were clearly a joke, thus no apprehension of force was caused.

It is important to note the distinction between apprehension and fear. A victim may expect immediate force without being in fear of it; an assault will occur either way.

(ii) The victim apprehends that use of force will be immediate

It most cases this is a simple point to establish, a defendant shakes his fist, the victim fears he will be hit in a matter of seconds. However, some cases have been met with contentious rulings in relation to this issue. There is not an exact definition of what ‘immediate’ has come to mean but the following case examples provide some insight.

In Smith v Superintendent of Woking Police [1983] Crim LR 323, the defendant stood up next to the window of a ground floor flat belonging to a woman living alone. She was terrified as he just stood there staring at her through the window. At trial the defendant argued there was no assault as the force apprehended was not immediate. He was outside and could not get to her without making his way inside. The Court held that despite this, the victim was clearly afraid by the prospect of some immediate violence. It was not thus unnecessary for the prosecution to establish exactly what the victim feared would happen as a general apprehension was sufficient.

Ireland came to a similar ruling whereby silent telephone calls were held to cause apprehension of immediate force as the phone calls had placed the defendant in immediate contact with the victims and the victims were placed in immediate fear. It was not necessary for there to be any physical proximity.

The point that can seemingly be taken from the presiding case law is that, in cases where the victims have no way of knowing what might happen, immediacy is satisfied.

In the same sense that words can negate an assault, they can also negate immediacy.

1.1.3 Mens Rea

The mens rea for assault is intending the victim to cause the apprehension of unlawful force or foreseeing that the victim might be caused such apprehension. This involves an element of subjective recklessness as was confirmed in the case of Savage andParmenter [1992] 1 AC 699, meaning the defendant themselves must have realised the risk of causing an apprehension of violence.

1.1.4 Type of Harm

No harm needs to occur for a technical assault conviction.

1.2 Battery

If an assault is understood to be an apprehension of force, a battery can be explained in simplistic terms as the actual use of unlawful force.

1.2.1 Actus Reus

The actus reus of this offence is the application of unlawful force on another. This application is usually direct, thus the defendant himself physically applies the force to the victim’s body. However, this does not need to be the case and force can also be applied indirectly.

On a basic level this can involve applying force through another medium. For example, consider the case of Fagan v Metropolitan Police Commissioner[1969] 1 QB 439, where driving a car over a person’s foot was held to be a qualifying application for the purposes of battery.

On a more indirect level, this can also involve application of force to one person which causes the application to another. This point was demonstrated in Haystead v DPP [2000] 3 All ER 690 where the defendant who punched a woman holding a baby, causing her to drop the baby, was found guilty of the battery to the baby.

R v Thomas [1985] Crim LR 677 confirmed that touching a person’s clothes can be sufficient as they do not need to feel the force directly. A battery can also be committed where the behaviour was intended as affectionate, as was confirmed in R v Braham [2013] EWCA Crim 3.

1.2.2 Mens Rea

The mens rea for battery involves either intention or recklessness as to the application of force.

1.3 Charging and Sentencing

Assault and battery are summary offence. S.39 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988 sets out that the maximum sentence is six months imprisonment and/or a fine.

2.0 Assault Occasioning Actual Bodily Harm

This offence encompasses those assaults where a more serious injury is caused to the victim. Liability for the offence is constructed from liability for the lessor offence of common assault. It is a result crime and must result in actual bodily harm.

2.1 Actus Reus

The actus reus of this offence consists of two parts:

- The defendant must commit an assault.

- The assault must cause actual bodily harm.

The defendant must commit an assault.

The term assault is properly taken to mean either an assault or a battery. Therefore, the actus reus and mens rea for either of these offences must be established. No additional mens rea is required.

The assault must cause actual bodily harm.

It must be established that the defendant’s assault caused the victim to suffer actual bodily harm which is defined in R v Donovan [1934] 2 KB 498 as an injury that is more than transient or trifling. R v Miller [1954] 2 All ER 529 clarified this further stating it to be any hurt or injury calculated to interfere with the health and comfort of the victim. However, R v Chan Fook [1994] 1 WLR 689 qualified this somewhat stating that the inclusion of the word ‘actual’ indicates that the injury whilst not needing to be permanent, cannot be so trivial so as to be wholly insignificant.

Ireland established that ABH can encompass psychiatric harm, however Chan Fook has clarified that this does not go as far as including distressing emotions or any state of mind which does not amount to a recognised clinical condition.

2.2 Mens Rea

No additional mens rea is required for this offence. R v Roberts [1978] Crim LR 44 confirms that the mens rea for the basic offence is sufficient.

2.3 Charging and Sentencing

The offence of assault occasioning actual bodily harm is charged under s47 of the Offences Against the Persons Act 1861 and shall be liable to imprisonment of a term not exceeding seven years.

3.0 Defences

Consent

Consent may operate as a defence to a charge of assault, battery or the causing of actual bodily harm.

Collins v Wilcock [1984] 3 All ER 374 established that all impliedly consent to some level of physical contact in day to day life. Without this it would be very difficult to have a functioning society. Consent becomes a more contentious issue in situations where more serious harm is caused as the law places limits to the level of harm an individual is entitled to consent to.

3.1 Consent can be given expressly or impliedly

Collins v Wilcock establishes that consent is automatically implied where there is jostling in busy places and other day to day activities, provided no more force was used than is reasonably necessary in the circumstances. Consent can be implied in other situations too. For example, implied consent to affectionate touching in a relationship.

3.2 Genuine Consent?

For consent to be genuine it must be given in the absence of fraud, by a person who is fully able to comprehend the nature of what they are consenting to. Children and adults who are found to lack capacity bear further consideration.

Even where the subject has capacity to consent this consent can be vitiated by fraud as to the (i) identity of the person or (ii) the nature and quality of the act.

Is the victim legally allowed to consent?

The law will only allow an individual to consent to cases that do not involve an act of violence. This is due to the fact that it is not considered to be in the public interest to allow individuals to hurt each other. Accordingly, in cases where ABH or more serious harm is intended and or caused Attorney General’s Reference No 6 of 1980 [1981] states that a person’s consent is irrelevant and cannot prevent criminal liability. The Court in Attorney General’s Reference No 6 and R v Brown [1994] 1 AC 212 provide some caveats to this, giving specific categories of scenarios where it is in the public interest to allow individuals to consent to such harm.

- Reasonable surgical interference

- Properly conducted games and sports

- Tattooing, piercing and male circumcision

- Horseplay

- Sexual Relations

4.1.3 Assault, Battery and ABH Lecture – Hands on Examples

The following scenario aims to test your knowledge of this topic and your ability to apply what you have just learned in a real life setting.

Have a look at the following passage and try to pull out the material facts and legal issues. Highlight these as you go through and jot down any key points, ideas, or relevant law that come to mind. If you’re feeling confident then once you have done this you can have a go at producing an answer.

If you’re not ready to go it alone just yet, there’s no need to panic! Answering these questions takes a lot of practice and if this is the first time you have done it then it is going to be tricky. A guideline answer is provided below, outlining the key points you would need to address. Have a look at this and try and use it to help you produce your own answer, or to check the answer you have already produced.

Tim is really passionate about football and he loves everything to do with it. At work Tim and his colleagues have a fantasy football league and this gets very competitive. A lot of the time they will discuss the league together and argue over who has the best fantasy team each week. Tim goes to work on Monday morning furious as his his team has not done very well that week. Jack infuriates Tim by bragging loudly to Josh about how many points his team scored him that week. After sometime Tim turns around and raises his fist at Jack shouting, “if you say one more thing about this I will shut you up myself”.

Jack is afraid by this and says nothing, quietly resuming work. Josh however is annoyed at Tim for threatening his friend. As he is walking past Tim’s chair he pushes the back of the chair hard causing Tim to fall forward and hit his head. Tim is shaken by the shock of the push but luckily is not seriously hurt.

After work, Tim, Jack and Josh have planned to compete in the 5-aside football league they play in. Sophie, a girl that both Tim and Josh like, is going along to watch the game. Still annoyed at Josh for pushing him, Tim is really eager to out-do Josh in front of Sophie as he knows this will upset him. In the last few moments of the game the score is 0-0 and Tim spots an opportunity to win the ball just outside the penalty box of the other team. Fired up and keen to impress, Tim flies in for the tackle but in the heat of the moment horribly mistimes it. His boot crashes into Louis’ shin and sprains Louis’ankle.

Discuss the potential liability Tim and Josh for assault, battery and ABH in relation to the above scenario.

Guideline Answer

There are three issues at hand here:

(i) Tim’s threat to Jack

(ii) Josh pushing Tim

(iii) Tim tackling Louis

Once you have identified all three you need to break your answer down into subheadings and discuss each issue individually.

(i) Tim’s threat to Jack

- Consider first a possible offence of assault.

- Actus reus: Does Tim cause Jack to apprehend the application of force? Raising his fist would cause a person to apprehend an immediate application of force

- Is this apprehension of immediate force? No, similarly to Tuberville v Savage [1669] EWHC KB J25, the accompanying words “if you say one more thing” negate the assault as there is no immediacy. He will only be harmed in circumstances where he continues to speak and not right away.

- There is no application of force as Tim does not carry out his threat so there is no battery.

(ii) Josh pushing Tim

- First consider the possibility of an assault occurring. Does Josh cause Tim to apprehend the application of immediate unlawful force? A careful study of the facts shows us that he didn’t. Josh went up behind and there was no prior threat issued so Tim was not aware that the force was about to be applied. Accordingly, he was unable to apprehend the application of force so there can be no assault.

- Having established assess whether on the facts there can be a battery?

- Actus reus: Does Josh apply unlawful force to Tim?

- Applying Fagan v Metropolitan Police Commissioner [1969] 1 QB 439 and Haystead v DPP [2000] 3 All ER 690 it can be seen that the application of force can be indirect, therefore the push on the chair would suffice for the purposes of battery. The battery occurs when the chair causes Tim to fall forward and hit his head.

- Mens rea: Intention to apply force or recklessness as to whether force will be applied. It can be seen on the facts that Josh likely intended to apply the force to Tim when pushing the chair but in any case he was reckless as to whether pushing the chair would cause the application of force to Tim.

- Therefore, both elements of the offence are established and Josh will be liable for the battery on Tim.

- Possible s47 ABH liability? Actual bodily harm means an injury that is more than transient or trifling (R v Donovan [1934] 2 KB 498). R v Miller[1954] 2 All ER 529 clarified this further stating it to be any hurt or injury calculated to interfere with the health and comfort of the victim. However, R v Chan Fook [1994] 1 WLR 689 it was clarified that thiscannot be so trivial so as to be wholly insignificant. It is unlikely that contact to the head that causes no further damage would fulfil these definitions so no charge of ABH would be available in relation to Josh’s push.

(iii) Tim tackling Louis

- Assault:

- Actus reus: Did Tim cause Louis to apprehend the immediate application of force? This is likely where Louis saw Tim approaching him late and off the ball, however this is open to an interpretation of the facts and you should come to your own conclusion here.

- Mens rea: Tim was subjectively reckless as to causing the apprehension when mistiming his tackle.

- Battery:

- Actus reus: The unlawful application of force. This is satisfied as Tim’s tackle is late and off the ball and therefore outside the rules of the game.

- Mens rea: Tim is reckless as to whether force will be applied when going in for the late challenge.

- ABH:

- The battery causes Louis to break his leg which is harm of a nature that is clearly encompassed by both the Miller and Chan Fook definitions and also the CPS charging guidelines.

- There is no additional mens rea requirement for the ABH so having satisfied the actus reus and mens rea for battery and the actus reus for ABH it is likely that Tim would be liable for the ABH of Louis.

- However, if it can be found Louis consented to the harm this will negate the offence. Applying Attorney General’s Reference No 6 of 1980 [1981] where ABH or more serious harm is intended and or caused a person’s consent is irrelevant. As ABH was caused here then any consent by Louis would be prima facie invalid. However,Attorney General’s Reference No 6 of 1980 and R v Brown [1994] 1 AC 212 provide exceptions to this where it may be in the public interest to allow consent. The appropriate exception here is for the provision of properly conducted sports.

- What is properly conducted? This refers to a sport played according to recognised rules. As Tim’s tackle was late and off the ball it cannot be said to be within the rules of the game. However,R v Barnes [2004] EWCA Crim 3246states that an instinctive error, reaction or misjudgment in the heat of a game should not be classed as criminal activity. Applying this to the present facts it would appear that Tim’s conduct falls with this definition as it was a misjudged error in the heat of the game, therefore Louis’ would be held to consent to the harm and Tim will have no liability for the incident.