DEATH PENALTY: CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is a government-sanctioned practice whereby a person is killed by the state as a punishment for a crime. The sentence that someone be punished in such a manner is referred to as a death sentence, whereas the act of carrying out the sentence is known as an execution. Crimes that are punishable by death are known as capital crimes or capital offences, and they commonly include offences such as murder, mass murder, terrorism, treason, espionage, offenses against the State, such as attempting to overthrow government, piracy, drug trafficking, war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, but may include a wide range of offences depending on a country. Etymologically, the term capital (lit. “of the head”, derived via the Latin capitalis from caput, “head”) in this context alluded to execution by beheading.

Fifty-six countries retain capital punishment, 106 countries have completely abolished it de jure for all crimes, eight have abolished it for ordinary crimes (while maintaining it for special circumstances such as war crimes), and 28 are abolitionist in practice.

Capital punishment is a matter of active controversy in several countries and states, and positions can vary within a single political ideology or cultural region. In the European Union, Article 2 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union prohibits the use of capital punishment. The Council of Europe, which has 47 member states, has sought to abolish the use of the death penalty by its members absolutely, through Protocol 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights. However, this only affects those member states which have signed and ratified it, and they do not include Armenia, Russia, and Azerbaijan.

The United Nations General Assembly has adopted, in 2007, 2008, 2010, 2012 and 2014,non-binding resolutions calling for a global moratorium on executions, with a view to eventual abolition. Although most nations have abolished capital punishment, over 60% of the world’s population live in countries where the death penalty is retained, such as China, India, the United States, Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Iran, among all mostly Islamic countries, as is maintained in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Sri Lanka.China is believed to execute more people than all other countries combined.

According to a number of sources capital punishment, which is sometimes used interchangeably with the death penalty, is defined as the legal authorized killing of another as punishment for a crime.

This scope was widely employed in case matters such as murder and treason but not limited to. In the United States the federal government and roughly three-fourths of the states retain the use of capital punishment. States such as Connecticut, Maryland, and New Mexico have abolished the practice all together before this issue became a national issuer. Thirty two states have laws on the books legalizing capital punishment. Capital punishment in the 21 century is a subject that should be revisited and revised. Sense it foundation to recent years, much debate has stirred regarding the validity under the law, the effects on our society and the morally of capital punishment.

Those that are pro-capital punishment/ death penalty make the argument that it is vital and necessary in today’s world, stating claims that it is in fact an effective deterrent to criminal behavior. Those that stand against the use of capital punishment often question the constitutionality of the practice and also state the case that capital punishment is not effective and severely flawed, mostly targeting low income individuals and minorities.

Debates have gone on for years questioning the constitutional validity of capital punishment, whether or not this practice violates certain rights guaranteed by the United States Constitution, such as the 5th, 8th, as well as the 14th Amendments. Opponent’s such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) sight these rights are being violated in capital punishment cases.

The ACLU goes on to state where they stand on the issue by stating,’ The capital punishment system is discriminatory and arbitrary and inherently violated the Constitutional ban against cruel and unusual punishment.’

U.S District Judge Jed S. Rakoff of the Southern District of New York stated in his July 1, 2002 ruling United States v. Quinones that the death penalty violated the due process clause of the 5th Amendment. He states that the Federal Death Penalty Act cut off the opportunity for exoneration, denies due process and, indeed, is tantamount to foreseeable, state sponsored murder of innocent human beings. The 5th Amendment clearly speaks to due process and it can be interpreted that with newly-developed techniques. The 8th Amendment, ratified in 1791 goes on to address another violation of capital punishment, ‘Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishment inflicted.’ Opponents point to the cruel and unusual clause of the 8th Amendment, stating this as a violation to human beings.

‘Death is not only an unusually severe punishment, unusual in its pain, in its finality, and in its enormity, but it serves no penal purpose more effectively than a less severe punishment,’ William J. Brennan, JD Justice of the United States Supreme Court July 2, 1976 dissenting opinion in Gregg v. Georgia. It was July 2, 1976 that the United States Supreme Court reaffirmed in Gregg v. Georgia of the court’s acceptance of capital punishment here in the United States.

U.S Supreme Court Justice Marshall also expressed his views in the Gregg v. Georgia case in which he articulated, ‘Capital punishment does not deter crime and that our society has evolved to the point that it is no longer an appropriate vehicle for expressing retribution.’ During an October 2010 interview U.S Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens remarked that his vote in the decision was regrettable, this is in fact a growing trend among many Americans today for a host of reasons. Another thing we must look into is the cost it has on our economy and the toll it has on the family.

Capital Punishment takes a toll on us all, from the smallest unit, the family, to our national government. Professor of Law & Public Health Jeffrey Fagan published an essay titled, ‘Capital Punishment: Deterrent Effects & Capital Cost.’ Professor Fagan goes on to state the cost of each execution can cost taxpayers anywhere between 2.5 to 5 million dollars, and he goes on to ask whether this money can better serve the community in another capacity, after all there are alternatives to the death penalty. Life behind bars without the possibility of parole is only one example of an alternative that could be used in place there of the death penalty.

The 52nd Governor of New York Mario Cuomo a strong advocate to abolish the death penalty addressed this issue in an October 2 2011 article title, ‘Death Penalty is dead wrong: It’s time to outlaw capital punishment in America- completely’.

Governor Cuomo of New York mentioned, ‘True life imprisonment is a more effective deterrent than capital punishment.’ He goes on to state,’ to most inmates, the thought of living a lifetime behind bars only to die in a cell, is worse than the quick, final termination of the electric chair or lethal injection.’

Another factor to keep in mind is that capital punishment trials and the appeals that are sure to follow can be somewhat lengthy and leaving taxpayers to bear the cost.

Families suffer the most in capital punishment cases, leaving kids to fill the void of a missing parent and loving mothers and fathers to cope with the fact of their child possibly facing death.

American support of capital punishment has been on the decline in recent years and this hold especially true among church goers. During 2001- 2004 a Gallop Poll titled, ‘Who Supports the Death Penalty’ revealed that those who attend religious service regularly are less likely to endorse capital punishment. March 21, 2005 a Zogby Poll revealed a third of Catholics who once supported capital punishment now oppose it, citing respect of life.

Younger Catholics are among those who least likely to support capital punishment according to the march 21, 2005 Zogby Poll.

According to Death Penalty Information (DPIC) today more than two-thirds of the world, countries and mostly all of Europe have abandoned capital punishment. Also, since 1976, at least 142 inmates have been freed row death row after evidence of their innocence emerged Lack of an effective attorney, execution methods and above all executing the innocent are all reasons why this poor public policy should be at the very least reconsidered for repeal or revised.

Historical Considerations

Capital punishment for murder, treason, arson, and rape was widely employed in ancient Greece under the laws of Draco (fl. 7th century BCE), though Plato argued that it should be used only for the incorrigible. The Romans also used it for a wide range of offenses, though citizens were exempted for a short time during the republic. It also has been sanctioned at one time or another by most of the world’s major religions. Followers of Judaism and Christianity, for example, have claimed to find justification for capital punishment in the biblical passage “Whosoever sheddeth man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed” (Genesis 9:6).

Yet capital punishment has been prescribed for many crimes not involving loss of life, including adultery and blasphemy.The ancient legal principle Lex talionis(talion)—“an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, a life for a life”—which appears in the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi, was invoked in some societies to ensure that capital punishment was not disproportionately applied.

The prevalence of capital punishment in ancient times is difficult to ascertainprecisely, but it seems likely that it was often avoided, sometimes by the alternative of banishment and sometimes by payment of compensation.

For example, it was customary during Japan’s peaceful Heian period (794–1185) for the emperor to commute every death sentence and replace it with deportationto a remote area, though executions were reinstated once civil war broke out in the mid-11th century.In Islamic law, as expressed in the Qurʾān, capital punishment is condoned.Although the Qurʾān prescribes the death penalty for several ḥadd (fixed) crimes—including robbery, adultery, and apostasy of Islam—murder is not among them. Instead, murder is treated as a civil crime and is covered by the law of qiṣās (retaliation), whereby the relatives of the victim decide whether the offender is punished with death by the authorities or made to pay diyah(wergild) as compensation.

Death was formerly the penalty for a large number of offenses in England during the 17th and 18th centuries, but it was never applied as widely as the law provided.

As in other countries, many offenders who committed capital crimes escaped the death penalty, either because juries or courts would not convict them or because they were pardoned, usually on condition that they agreed to banishment; some were sentenced to the lesser punishment of transportation to the then American colonies and later to Australia.Beginning in the Middle Ages, it was possible for offenders guilty of capital offenses to receive benefit of clergy, by which those who could prove that they were ordained priests (clerks in Holy Orders) as well as secular clerks who assisted in divine service (or, from 1547, a peer of the realm) were allowed to go free, though it remained within the judge’s power to sentence them to prison for up to a year, or from 1717 onward to transportation for seven years.

Because during medieval times the only proof of ordination was literacy, it became customary between the 15th and 18th centuries to allow anyone convicted of a felony to escape the death sentence by proving that he (the privilege was extended to women in 1629) could read. Until 1705, all he had to do was read (or recite) the first verse from Psalm 51 of the Bible—“Have mercy on me, O God, according to your steadfast love; according to your abundant mercy blot out my transgressions”—which came to be known as the “neck verse” (for its power to save one’s neck).

To ensure that an offender could escape death only once through benefit of clergy, he was branded on the brawn of the thumb (M for murder or T for theft).Branding was abolished in 1779, and benefit of clergy ceased in 1827.From ancient times until well into the 19th century, many societies administered exceptionally cruel forms of capital punishment.

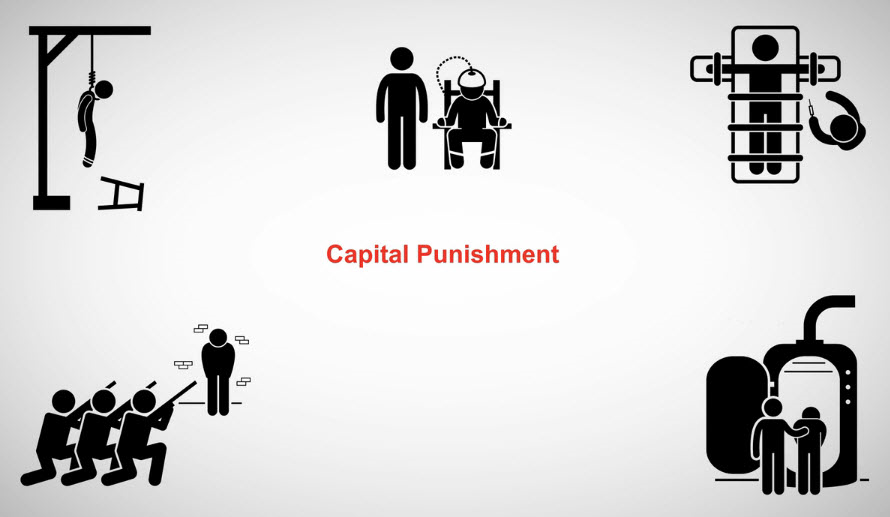

In Rome the condemned were hurled from the Tarpeian Rock (see Tarpeia); for parricide they were drowned in a sealed bag with a dog, cock, ape, and viper; and still others were executed by forced gladiatorial combat or by crucifixion. Executions in ancient China were carried out by many painful methods, such as sawing the condemned in half, flaying him while still alive, and boiling.Cruel forms of execution in Europe included “breaking” on the wheel, boiling in oil, burning at the stake, decapitation by the guillotine or an axe, hanging, drawing and quartering, and drowning. Although by the end of the 20th century many jurisdictions (e.g., nearly every U.S. state that employs the death penalty, Guatemala, the Philippines, Taiwan, and some Chinese provinces) had adopted lethal injection, offenders continued to be beheaded in Saudi Arabia and occasionally stoned to death (for adultery) in Iran and Sudan.

Other methods of execution were electrocution, gassing, and the firing squad.

Historically, executions were public events, attended by large crowds, and the mutilated bodies were often displayed until they rotted. Public executions were banned in England in 1868, though they continued to take place in parts of the United States until the 1930s. In the last half of the 20th century, there was considerable debate regarding whether executions should be broadcast on television, as has occurred in Guatemala. Since the mid-1990s public executions have taken place in some 20 countries, including Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Nigeria, though the practice has been condemned by the United Nations Human Rights Committee as “incompatible with human dignity.”

In many countries death sentences are not carried out immediately after they are imposed; there is often a long period of uncertainty for the convicted while their cases are appealed. Inmates awaiting execution live on what has been called “death row”; in the United States and Japan, some prisoners have been executed more than 15 years after their convictions. The European Union regards this phenomenon as so inhumane that, on the basis of a binding ruling by the European Court of Human Rights (1989), EU countries may extradite an offender accused of a capital crime to a country that practices capital punishment only if a guarantee is given that the death penalty will not be sought.

Arguments For And Against Capital Punishment

Capital punishment has long engendered considerable debate about both its morality and its effect on criminal behaviour. Contemporary arguments for and against capital punishment fall under three general headings: moral, utilitarian, and practical.

Moral arguments

Supporters of the death penalty believe that those who commit murder, because they have taken the life of another, have forfeited their own right to life. Furthermore, they believe, capital punishment is a just form of retribution, expressing and reinforcing the moral indignation not only of the victim’s relatives but of law-abiding citizens in general. By contrast, opponents of capital punishment, following the writings of Cesare Beccaria (in particular On Crimes and Punishments [1764]), argue that, by legitimizing the very behaviour that the law seeks to repress—killing—capital punishment is counterproductive in the moral message it conveys. Moreover, they urge, when it is used for lesser crimes, capital punishment is immoral because it is wholly disproportionate to the harm done.Abolitionists also claim that capital punishment violates the condemned person’s right to life and is fundamentally inhuman and degrading.

Although death was prescribed for crimes in many sacred religious documents and historically was practiced widely with the support of religious hierarchies, today there is no agreement among religious faiths, or among denominations or sects within them, on the morality of capital punishment. Beginning in the last half of the 20th century, increasing numbers of religious leaders—particularly within Judaism and Roman Catholicism—campaigned against it. Capital punishment was abolished by the state of Israel for all offenses except treason and crimes against humanity, and Pope John Paul II condemned it as “cruel and unnecessary.”

Utilitarian arguments

Supporters of capital punishment also claim that it has a uniquely potent deterrent effect on potentially violent offenders for whom the threat of imprisonment is not a sufficient restraint. Opponents, however, point to research that generally has demonstrated that the death penalty is not a more effective deterrent than the alternative sanction of life or long-term imprisonment.

Practical arguments

There also are disputes about whether capital punishment can be administered in a manner consistent with justice. Those who support capital punishment believe that it is possible to fashion laws and procedures that ensure that only those who are really deserving of death are executed. By contrast, opponents maintain that the historical application of capital punishment shows that any attempt to single out certain kinds of crime as deserving of death will inevitably be arbitrary and discriminatory.

They also point to other factors that they think preclude the possibility that capital punishment can be fairly applied, arguing that the poor and ethnic and religious minorities often do not have access to good legal assistance, that racial prejudice motivates predominantly white juries in capital cases to convict black and other nonwhite defendants in disproportionate numbers, and that, because errors are inevitable even in a well-run criminal justice system, some people will be executed for crimes they did not commit. Finally, they argue that, because the appeals process for death sentences is protracted, those condemned to death are often cruelly forced to endure long periods of uncertainty about their fate.

The Abolition Movement

Under the influence of the European Enlightenment, in the latter part of the 18th century there began a movement to limit the scope of capital punishment. Until that time a very wide range of offenses, including even common theft, were punishable by death—though the punishment was not always enforced, in part because juries tended to acquit defendants against the evidence in minor cases. In 1794 the U.S. state of Pennsylvania became the first jurisdiction to restrict the death penalty to first-degree murder, and in 1846 the state of Michigan abolished capital punishment for all murders and other common crimes.

In 1863 Venezuela became the first country to abolish capital punishment for all crimes, including serious offenses against the state (e.g., treason and military offenses in time of war). Portugal was the first European country to abolish the death penalty, doing so in 1867; by the early 20th century several other countries, including the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Italy, had followed suit (though it was reintroduced in Italy under the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini). By the mid-1960s some 25 countries had abolished the death penalty for murder, though only about half of them also had abolished it for offenses against the state or the military code.

For example, Britain abolished capital punishment for murder in 1965, but treason, piracy, and military crimes remained capital offenses until 1998.

During the last third of the 20th century, the number of abolitionist countries increased more than threefold. These countries, together with those that are “de facto” abolitionist—i.e., those in which capital punishment is legal but not exercised—now represent more than half the countries of the world. One reason for the significant increase in the number of abolitionist states was that the abolition movement was successful in making capital punishment an international human rights issue, whereas formerly it had been regarded as solely an internal matter for the countries concerned.In 1971 the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution that, “in order fully to guarantee the right to life, provided for in…the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” called for restricting the number of offenses for which the death penalty could be imposed, with a view toward abolishing it altogether.

This resolution was reaffirmed by the General Assembly in 1977. Optional protocols to the European Convention on Human Rights (1983) and to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1989) have been established, under which countries party to the convention and the covenant undertake not to carry out executions.The Council of Europe (1994) and the EU (1998) established as a condition of membership in their organizations the requirement that prospective member countries suspend executions and commit themselves to abolition.

This decision had a remarkable impact on the countries of central and eastern Europe, prompting several of them—e.g., the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia—to abolish capital punishment.

In the 1990s many African countries—including Angola, Djibouti, Mozambique, and Namibia—abolished capital punishment, though most African countries retained it. In South Africa, which formerly had one of the world’s highest execution rates, capital punishment was outlawed in 1995 by the ConstitutionalCourt, which declared that it was incompatible with the prohibition against cruel, inhuman, or degrading punishment and with “a human rights culture.”

Capital Punishment In The Early 21st Century

Despite the movement toward abolition, many countries have retained capital punishment, and, in fact, some have extended its scope. More than 30 countries have made the importation and possession for sale of certain drugs a capital offense. Iran, Singapore, Malaysia, and the Philippines impose a mandatory death sentence for the possession of relatively small amounts of illegal drugs. In Singapore, which has by far the highest rate of execution per capita of any country, about three-fourths of persons executed in 2000 had been sentenced for drug offenses. Some 20 countries impose the death penalty for various economic crimes, including bribery and corruption of public officials, embezzlement of public funds, currency speculation, and the theft of large sums of money.

Sexual offenses of various kinds are punishable by death in about two dozen countries, including most Islamic states.In the early 21st century there were more than 50 capital offenses in China.Despite the large number of capital offenses in some countries, in most years only about 30 countries carry out executions. In the United States, where roughly 60 percent of the states and the federal government have retained the death penalty, about two-thirds of all executions since 1976 (when new death penalty laws were affirmed by the Supreme Court) have occurred in just six states—Texas, Virginia, Florida, Missouri, Louisiana, and Oklahoma. China was believed to have executed about 1,000 people annually (no reliable statistics are published) until the first decade of the 21st century, when estimates of the number of deaths dropped sharply.

Although the number of executions worldwide varies from year to year, some countries—including Belarus, Congo (Kinshasa), Iran, Jordan, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Yemen—execute criminals regularly. Japan and India also have retained the death penalty and carry out executions from time to time.

In only a few countries does the law allow for the execution of persons who were minors (under the age of 18) at the time they committed their crime. Most such executions, which are prohibited by the Convention on the Rights of the Childand the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, have occurred in the United States, which has not ratified the convention and which ratified the covenant with reservations regarding the death penalty.

Beginning in the late 1990s, there was considerable debate about whether the death penalty should be imposed on the mentally impaired; much of the controversy concerned practices in the United States, where more than a dozen such executions took place from 1990 to 2001 despite a UN injunction against the practice in 1989.In 2002 and 2005, respectively, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the execution of the mentally impaired and those under age 18 was unconstitutional, and in 2014 it held that states could not define such mental impairment as the possession of an IQ (intelligence quotient) score of 70 or below.

The court banned the imposition of the death penalty for rape in 1977 and specifically for child rape in 2008.

In the late 1990s, following a series of cases in which persons convicted of capital crimes and awaiting execution on death row were exonerated on the basis of new evidence—including evidence based on new DNA-testing technology—some U.S. states began to consider moratoriums on the death penalty. In 2000 Illinois Gov. George Ryan ordered such a moratorium, noting that the state had executed 12 people from 1977 to 2000 but that the death sentences of 13 other people had been overturned in the same period.A number of states subsequently abolished capital punishment, including New Jersey (2007), Illinois (2011), Connecticut (2012), and Washington (2018). Further bolstering abolition efforts in the United States was California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s announcement of a moratorium on capital punishment in 2019.