A trust is created by a settlor, who transfers title to some or all of his or her property to a trustee, who then holds title to that property in trust for the benefit of the beneficiaries. The trust is governed by the terms under which it was created.

A trust is a three-party fiduciary relationship in which the first party, the trustor or settlor, transfers (“settles”) a property (often but not necessarily a sum of money) upon the second party (the trustee) for the benefit of the third party, the beneficiary.

A testamentary trust is created by a will and arises after the death of the settlor. An inter vivos trust is created during the settlor’s lifetime by a trust instrument. A trust may be revocable or irrevocable; in the United States, a trust is presumed to be irrevocable unless the instrument or will creating it states it is revocable, except in California, Oklahoma and Texas, in which trusts are presumed to be revocable until the instrument or will creating them states they are irrevocable. An irrevocable trust can be “broken” (revoked) only by a judicial proceeding.

Trusts and similar relationships have existed since Roman times.

The trustee is the legal owner of the property in trust, as fiduciary for the beneficiary or beneficiaries who is/are the equitable owner(s) of the trust property. Trustees thus have a fiduciary duty to manage the trust to the benefit of the equitable owners. They must provide a regular accounting of trust income and expenditures. Trustees may be compensated and be reimbursed their expenses. A court of competent jurisdiction can remove a trustee who breaches his/her fiduciary duty. Some breaches of fiduciary duty can be charged and tried as criminal offences in a court of law.

A trustee can be a natural person, a business entity or a public body. A trust in the United States may be subject to federal and state taxation.

A trust is created by a settlor, who transfers title to some or all of his or her property to a trustee, who then holds title to that property in trust for the benefit of the beneficiaries. The trust is governed by the terms under which it was created. In most jurisdictions, this requires a contractual trust agreement or deed. It is possible for a single individual to assume the role of more than one of these parties, and for multiple individuals to share a single role.For example, in a living trust it is common for the grantor to be both a trustee and a lifetime beneficiary while naming other contingent beneficiaries.

Trusts have existed since Roman times and have become one of the most important innovations in property law. Trust law has evolved through court rulings differently in different states, so statements in this article are generalizations; understanding the jurisdiction-specific case law involved is tricky. Some U.S. states are adapting the Uniform Trust Code to codify and harmonize their trust laws, but state-specific variations still remain.

An owner placing property into trust turns over part of his or her bundle of rights to the trustee, separating the property’s legal ownership and control from its equitable ownership and benefits. This may be done for tax reasons or to control the property and its benefits if the settlor is absent, incapacitated, or deceased. Testamentary trusts may be created in wills, defining how money and property will be handled for children or other beneficiaries.

While the trustee is given legal title to the trust property, in accepting the property title, the trustee owes a number of fiduciary duties to the beneficiaries. The primary duties owed include the duty of loyalty, the duty of prudence, the duty of impartiality. A trustee may be held to a very high standard of care in their dealings, in order to enforce their behavior. To ensure beneficiaries receive their due, trustees are subject to a number of ancillary duties in support of the primary duties, including a duties of openness and transparency; duties of recordkeeping, accounting, and disclosure. In addition, a trustee has a duty to know, understand, and abide by the terms of the trust and relevant law. The trustee may be compensated and have expenses reimbursed, but otherwise must turn over all profits from the trust properties.

There are strong restrictions regarding a trustee with conflict of interests. Courts can reverse a trustee’s actions, order profits returned, and impose other sanctions if they finds a trustee has failed in any of their duties. Such a failure is termed a breach of trust and can leave a neglectful or dishonest trustee with severe liabilities for their failures. It is highly advisable for both settlors and trustees to seek qualified legal counsel prior to entering into a trust agreement.

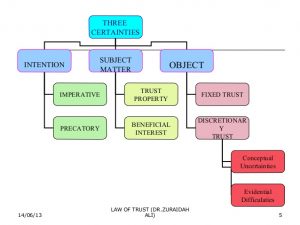

The three certainties enshrined in the law of trusts serve to guarantee that trusts are imbued with clarity and thus enforceability. It is clearly necessary to ensure that trust property can be specified with precision and dealt with precisely in accordance with the intentions of the settlor. If there is ambiguity the courts would rather allow a trust to fail than take the chance of permitting the inappropriate use of the putative settler’s property. Furthermore the certainties are an important safeguard against the risk of fraud, which is ever present in substantial property transfers.

Defining the Three Certainties

In the landmark case of Knight v Knight (1840) Lord Langdale set out the three certainties necessary to constitute a legally sound private express trust settlement and in so doing he succinctly defined the expectations the law imposes on the settlor:

- Certainty as to the settlor’s intention to establish a formal trust of property;

Generally speaking it is not necessary to create a trust in writing, and trusts do not even need to be declared orally. As a minimum pragmatism may intervene to ensure that a trust can be inferred from conduct of the settlor (although this is quite rare, especially in modern times.) That said, whether by words written or oral, or inferred by conduct, the intention of the settlor that a binding fiduciary obligation (and not just a moral wish) is to be imposed on the trustees must be clear, and unambiguous. - Certainty as to the property (subject matter) to constitute the trust;

The intended property of the trust must also be clear and unambiguous: it must be described with sufficient clarity and defined in such a way that the assets can be ascertained with certainty. If subject matter is uncertain the transaction will fail and ownership in property will not be transferred. The fact uncertainty of subject matter is fatal to a trust even though the range of property may have been averred to in the purported settlement was underlined in the case of Palmer v Simmonds (1854) where the phrase “the bulk of my residuary estate” was deemed inadequate to identify any particular portion of the property. Moreover, even where the trust property is clearly defined, the share or shares in that property to which the beneficiaries are entitled must also be clearly defined. - Certainty as to the persons (or objects) who are to benefit.

Beneficiaries must be identified with sufficient clarity that they can be ascertained with certainty. Trusts must also be deemed to be “administratively workable” (see Re Baden’s Deed Trusts (No.1) McPhail v. Doulton [1971] ).

The Three Certainties in Application

The three conditions stated above are cumulative and unless they are all satisfied no effective trust can come into being. If anything, as the judgment of Cotton LJ in Re Adams and the Kensington Vestry (1884) and inter alia, Re Steele’s WT (1948) confirms, the trend since Knight v Knight has in general to impose stricter requirements in terms of certainty and the proof necessary in modern times must be compelling in order to settle a trust.

Pragmatism and emotion do not always influence the court. The certainties must at least be respected so as to define the basic parameters of the trust. In Re Kolb’s WT (1962) the testator referred to “blue chip securities” – which is a term in common usage to designate large public companies considered a safe investment. However, because the term has no specific technical meaning Cross J ruled that the clause could not be delineated with sufficient precision and therefore that it could not be upheld.

That said, when one deals with trust settlement one is dealing with unique human components and circumstances and therefore a degree of pragmatism must be applied to do justice between the parties. Often judges are in the difficult situation of trying to second guess the wishes of a deceased party, and to adhere fairly to his wishes. Consistency is not always possible as Lord Justice Lindley stressed in Re Hamilton [1895] :

“You must take the will which you have to construe and see what it means, and if you come to the conclusion that no trust was intended, you say so, although previous judges have said the contrary on some wills more or less similar to the one you have to construe.”

The determining factor must always be justice on the facts, and sometimes this will mean that the law becomes wrinkled to a certain extent. This, it is submitted is unavoidable, in particular in fields involving complex human interaction such as the law of trusts.

Pragmatism is also an essential component in the field of discretionary trusts, where there may be an attempt to enforce open-ended or amorphous obligations. In Re Baden’s Deed Trusts (No.1), McPhail v Doulton (1971) the court stated that trustees of a discretionary trust were bound to embark on a reasonable survey of the field of possible beneficiaries and thereafter turn their minds to the question as to which, if any, are deserving of support. Re Manisty’s Settlement considered the question of administrative workability devised in McPhail v Doulton, which arises if a class is drawn so wide as to be impossible to manage effectively. In Manistry’s Settlement the class in question was the entire world subject to a small excepted group and the power was in fact upheld. It is submitted that this suggests that there are boundaries to pragmatic intervention where at least the intention of the settlor is clear.

Commentary: What’s wrong with a little pragmatism and emotion?

It is probably true to assert that, to some extent, pragmatism and emotion have indeed distorted the court’s ability to interpret consistently the three certainties required for the creation of a trust. This is one characteristic of the English common law system and it is not necessarily a bad thing. Lord Denning was a brilliant but controversial judge, rising to Master of the Rolls in the Court of Appeal in the latter half of the twentieth century. He delivered many judgments grounded more firmly on pragmatism and emotion than on precedent. In so doing he secured fair play between the parties in most of his rulings (see for example DHN Foods Distributors Ltd v London Borough of Tower Hamlets (1976) ), although his critics are always quick to point to the fact that his judgments introduced a degree uncertainty and unpredictability, if not confusion, into the law (Adams v Cape Industries plc (1990) ).

The trust is a creature of equity and as a consequence it is submitted that it is perhaps more appropriate to allow the interplay of emotion and pragmatism in interpreting and applying trust law than in certain other circumstances and legal contexts. The three certainties are essential conditions for the creation of a legally recognised and enforceable trust. The certainties protect the interests of the settlor and beneficiaries, inform the trustees as to the precise extent of their obligations and permit the court to exercise control over what has long been an important legal mechanism. As such consistency is important and it is argued that it is necessary to ensure that any distortions caused by considerations of pragmatism or emotion are fully justified in the circumstances and against the backdrop of the wider field of law in which they sit.

In simple terms consistency is important in the context of applying the law of the three certainties in trust creation, but so is flexibility. A system of law that strives for consistency over considerations of pragmatism and emotion – which might be better described as fair play and natural justice – is a system of law in danger of sclerosis and iniquity. It should be noted that the law in this field is not seeking to regulate the size of widgets on a conveyor belt or homogenous financial transactions, it attempts to negotiate a complex web of sensitive and personal human interaction that is unique in each and every instance. It is submitted therefore that a certain degree of distortion is a necessary and welcome characteristic of the case-based regime that defines the application of the law of trusts.

In closing it is as well to bear in mind that the law of equity which gave rise to trust law was itself born out of a frustration and dissatisfaction with the rigid and unyielding mechanism that the common law had become. Pragmatism and the natural justice derived from precedents influenced by factors that can be broadly grouped as emotional are celebrated emblems of equity and in the opinion of this commentator, long may they remain so.

Bibliography

- Paul Todd (2000) Cases and Materials on Equity and Trusts. London: Blackstone Press Ltd

- David Parker et al, Parker and Mellows: The Modern Law of Trusts, (2003) Sweet and Maxwell.

- D.J. Hayton (2004) The Law of Trusts. London: Sweet and Maxwell

- Dennis Keenan (1995) Smith and Keenan’s English Law. London: Pitman Publishing

- Paul Todd (2005) Paul Todd’s The Law of Trusts:

http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/pntodd/trusts/trusts.htm - Alastair Hudson, Understanding Equity and Trusts Law, (2004), Cavendish Publishing.

- Angela Sydenham, Equity and Trusts, (2000) Sweet and Maxwell.