By Law Teacher

7.1 Trespass to the Person, Land and Goods – Introduction

Welcome to the first lesson of the seventh topic in this module guide – Trespass to the Person, Land and Goods! The torts of trespass are distinct from negligence in that they involve deliberate, intentional actions. This old body of law intersects with the criminal law and more modern statutory reforms, and so a proper understanding of how it persists today is crucial.

At the end of this section, you should be comfortable in understanding the torts of trespass to the person, to land and to goods. You will appreciate the defences that may be available to defendants in this regard, and, in understanding and utilising the body of case law relevant here, be able to apply the rules to a range of factual scenarios.

The section begins by discussing the various torts relating to trespass of the person. These include battery, assault, false imprisonment, indirect trespass from Wilkinson v Downton, and harassment. For each tort, the requisite elements are discussed and demonstrated, and a discussion of possible defences is conducted. The section then moves on to discuss trespass to land, defining the four elements of the tort and further rules and particularities surrounding this tort, before again a discussion of available defences is provided. Finally, the trespass to goods is discussed, with the elements and defences explored within the applicable case law.

Goals for this section:

- To understand the law relating to trespass.

Objectives for this section:

- To appreciate and be able to apply the rules relating to battery, assault, false imprisonment, indirect trespass and harassment.

- To be able to deal with the law surround the trespass to land.

- To be able to apply the law to factual scenarios relating to the trespass to goods.

- To understand what available defences there are for torts of trespass.

7.2 Trespass to the Person, Land and Goods Lecture

Trespass to the Person

Tort law has developed its own framework for claims against defendants who have acted to infringe personal rights. This includes the torts of battery, assault, false imprisonment and harassment.

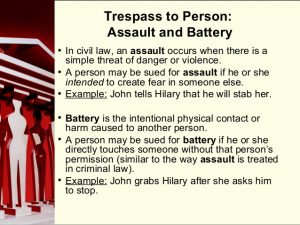

Battery

Battery simply involves the intentional and direct application of force to another person (either to their body or via their clothing). It is essential to note that it does not require injury or objective harm – an individual has a straightforward right to not be physically touched or moved by another person.

- The key feature of battery is intention – else every busy street would result in a litany of cases. The intention requirement be seen operating in Letang v Cooper [1965] 1 QB 232.

- Direct application of force is also a requirement of battery. This requirement should not be taken literally – a defendant can use a tool to inflict battery.

Indirect contact can still fulfil the ‘direct application’ requirement, Pursell v Horn [1838] 112 ER 966. Contact by a third party can also fulfil this requirement, given that the contract is instigated by the defendant. The key example here is Scott v Shepherd [1773] 96 ER 525.

The criminal law concept of transferred malice means that a defendant who intends direct contact with one party but instead hits another will be held liable for the contact with the ‘wrong’ victim. This can be seen in Livingstone v Ministry of Defence [1984] NI 356.

Whilst injury is generally not a prerequisite, the courts will distinguish between hostile and unhostile contact. As per Cole v Turner [1704] 6 Mod Rep 149, the “least touching in anger is a battery.” Whilst hostility is usually accompanied by a lack of consent on the part of the victim, non-consent will not always indicate hostile intent, F v West Berkshire Health Authority [1989] 2 AC 1.

Assault

Not to be confused with the everyday meaning of assault (as in attack), assault in criminal and tort law refers to situations in which an individual “causes another person to apprehend the infliction of immediate, unlawful force on his person”, as per Collins v Wilcock [1984] 1 WLR 1172. It often goes hand-in-hand with battery.

- Assault does not solely involve physical indications of violence – it is now the case that words and threats can constitute assault, as long as they fulfil the relevant criteria. Since assault is based around communication, even silence can constitute an assault. The issues of both words as assault and silence as assault appear in R v Ireland [1998] AC 147.

- Intention is a necessary component of assault. Thus, somebody who unwittingly acts in a way which causes another to apprehend an attack will not be liable – else someone walking down the street towards a baseball game holding a bat might find themselves in significant trouble.

- The fear of the victim must be reasonable. This reasonableness will be judged based on the facts which are available to the victim at the time of the assault, rather than the objective reality of the situation. This principle can be seen at work in R v St George [1840] 9 C&P 483.

It is a requirement of assault that the apprehended danger be of an immediate nature, Mbasogo v Logo Ltd (No. 1) [2005] EWHC 2034. Since assault is a matter of what the victim believes can happen in the immediate future, a threat the victim knows the defendant cannot carry out will not constitute assault, Thomas v National Union of Mineworkers [1986] Ch 20.

Defences to Assault and Battery

- Those with lawful authority will be protected from being held liable of either assault or battery. Thus, under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 the police can use reasonable force in order to arrest somebody (amongst other activities). Similarly, medical professionals can use reasonable force within certain situations specified by the Mental Health Act 1983.

It is important to note that people with lawful authority do not have the authority to do as they will – they still have to act reasonably. This can be seen in Collins v Wilcock [1984] 3 All ER 374.

- As can be seen in Collins, an individual can use reasonable force in self-defence. The force must be proportionate to the threat – since the purpose of the force is to repel to threat, it must be no more substantive than is necessary to do that, Revill v Newbury [1996] 2 WLR 239.

- Parents still have a right to use physical force to chastise a child. This right has important limits, however. The level of force inflicted must be proportional to the child’s behaviour (and has, in any case, an upper limit), and if the child does not understand the purpose of the punishment, the defence will fail, A v UK [1998] 2 FLR 959.

- If interference with another (i.e. battery) will protect them from a greater evil, or is otherwise necessary, then this will form a valid defence against battery. This is the essence of the ‘pushing someone from the path of a car’ discussed in F v West Berkshire Health Authority above.

- As with other torts, consent and contributory negligence form an absolute and partial defence respectively, to the torts of assault and battery.

False Imprisonment

False imprisonment is restraint without lawful authorisation. As long as the circumstances of false imprisonment exist, the victim does not need to even be aware that they are being falsely imprisoned before a case can be brought. This can be seen in Murray v Ministry of Defence [1988] 1 WLR 692.

The key element of false imprisonment is that it must involve a total loss of freedom – it will not arise in situations where the victim is merely prevented from proceeding in a particular direction. This can be seen in Bird v Jones [1845] 7 QB 742.

Defences to False Imprisonment:

- If the claimant is being detained on the basis that they need to meet a reasonable condition, then this will form a defence to a claim of false imprisonment. This can be seen in Robinson v Balmain New Ferry Co. Ltd [1910] AC 295.

Assuming the surrounding circumstances are reasonable, a claimant who has to wait a reasonable period of time for ‘release’ will not be considered as being falsely imprisoned. This can be seen in Herd v Weardale Steel, Coal and Coke Co Ltd. [1915] AC 67.

- Lawful Authority is a defence. The police have a reasonable right to restrain individuals in particular circumstances. However, if these circumstances are not in place, then cases can be brought against them for false imprisonment.

Mental health professionals also have a similar ability. It is also possible to lawfully detain an individual if they have a particular contagious disease, as per the Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984.

- As noted above, individuals can explicitly or impliedly consent to temporary imprisonment of some kind, as in Robinson. It is also feasible that an individual might contribute to their own detention – someone who pretends to shoplift and is then kept for longer than necessary by a security guard, for example, will reasonably be regarded as having contributed to the situation.

Wilkinson v Downton and Indirect Trespass

Although largely subsumed by the torts of negligence and harassment, the case of Wilkinson v Downton [1897] 2 QB 57 provides an action based on the infliction of indirect harm on another.This is essentially the tort of communicating information designed and intended to harm the well-being of an individual.

The elements of liability were more recently laid out in Wong v Parkside NHS Trust [2001] EWCA Civ 1721. The court identified three elements of the tort – actual harm in the form of physical or psychiatric injury, there must be intention, and the conduct must be of such a degree and such a nature that it was intended to cause harm. It was this third ground that Wong failed to meet.

It has only been successfully employed twice in Janvier v Sweeney [1919] 2 KB 216 and Khorasandjian v Bush [1993] QB 727. Nevertheless, Wilkinson remains good law, despite its function being overtaken by legislation.

Harassment

Thanks to the Harassment Act 1997, the tort of harassment now has a statutory definition. Its three elements are mentioned in s.1 of the act: “a course of conduct that the defendant knows or ought to know amounts to harassment of another.”

- Course of Conduct – As per s.7(3), this refers to conduct on two or more occasions – so one off instances are not covered. Conduct includes speech, as per s.7(4).

- That Amounts to Harassment – As per s.7(2) harassment is that which causes alarm or distress in the victim. Notably, this is subjective on the part of the victim.

- The Defendant Knows (Or Ought to Know) That It Amounts to Harassment – Examples include a campaign of threats against the employees and business partners of an medical animal research laboratory, in Daiichi v Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty [2004] 1 WLR 1503, workplace bullying in Majrowski v Guy’s and St. Thomas’s NHS Trust [2006] 2 WLR 125 (which recognised vicarious liability for the tort) and aggressively intrusive police questioning, in KD v Chief Constable of Hampshire [2005] EWHC 2550.

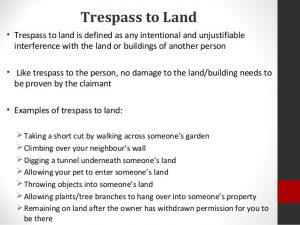

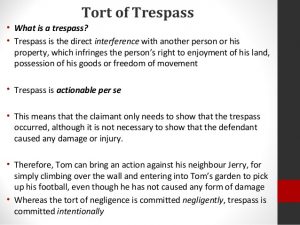

Trespass to Land

Trespass to land is the unjustified interference with the possession of land.There are four elements of the tort which need clarification: there must be direct interference, and that interference must be voluntary, but there is no need for awareness that trespassing is occurring, and there is no need for harm (it is actionable per se).

Direct Interference

There must essentially be some purposiveness to the interference with the land. This interference needn’t be particularly egregious. This can be seen in Gregory v Piper [1829] 9 B & C 591.

Voluntariness

The interference must be voluntary, as per Stone v Smith [1947] Style 65.

Awareness is not Necessary

Trespass caused by a mistake is still actionable. Similarly, someone who is mistaken as to their permission to enter onto land will still be committing a tort, as per Conway v George Wimpey & Co Ltd [1951] 2 KB 266.

No Harm Needed

Trespass to land, much like trespass to the person, is a matter of protecting rights, rather than preventing harm. Because of this, no harm need be shown before a trespass is actionable.

Further Trespass Rules

There are three particulars of trespass which bear mentioning.

- Firstly, ‘land’ should be given its proper property law definition – it includes the air above a piece of property and the soil below. There is an upper and lower height limit to this cube, however, as seen in Bernstein v Skyviews and General Ltd [1978] QB 479.

- Only those who have exclusive possession of a piece of land can sue for trespass – this means that tenants, guests, visitors or lodgers cannot.

- The rule of trespass ab initio states that where a defendant abuses their permission to enter a piece of land, then they will be treated as having trespassed from the moment they entered the land, as per The Six Carpenters Case [1572] EngR 452.

Trespass to Goods

This is an action in tort to deal with unwarranted inference with personal property – the tort of trespass to goods. This is covered in the Torts (Interference with Goods) Act 1977. The elements are largely the same as for trespass to land – direct interference with goods belonging to another.

Direct Interference

As with land, the tort is of direct interference. This essentially means an object must be physically affected – so moved or damaged. In contrast, unauthorised observation is not trespass, Malone v Metropolitan Police Commissioner [1979] Ch 344.

Awareness

As long as the defendant knows they are interfering with the object, then the fact that they did not know they were committing trespass will not form a defence.

This can be seen in Wilson v Lombank [1963] 1 WLR 1294. However, if the defendant mistakenly interferes with an object but doesn’t know that they are doing so, then this will form a defence, as in National Coal Board v JE Evans & Co (Cardiff) Ltd [1951] 2 KB 861.

It can therefore be seen that liability is strict when the trespassed object is known to the defendant, but fault based (like negligence) when they have no knowledge of it.

Harm is Not Necessary (Most of the Time)

When the interference is deliberate – then trespass is actionable per se – without damage (as per Transco Plc v United Utilities Water Plc [2005] EWHC 2784.) In contrast, if the interference is done unknowingly (so mistakenly hitting a hidden cable) then damage is necessary (as per Everitt v Martin [1953] NZLR 298.)

Possession

Trespass is a matter of interfering with possession, rather than ownership. It is thus possible for a possessor who is not an owner to bring an action for trespass, such as in the case of trustees, executors or administrators.

However, as per s.8 of the 1977 Act, a defendant can argue a defence if jus tertii (third party rights) – essentially, that a person other than the claimant has a greater right to the property, and thus that they are the proper claimant of the case. If this is the case, that third party will become a joint-claimant. This will occur rarely, however, since claimants are obliged to give full details of the nature of their ownership before the claim reaches court.

Defences to Trespass to Land and Goods

Under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, those with lawful authority can interfere with property and land within certain parameters – to execute a warrant, for example.

Consent and contributory negligence are available for trespass to land. Consent can operate within the trespass of goods, but as per s.11 of the Act, contributory negligence is not a defence where interference goods is intentional.

7.3 Trespass to the Person, Land and Goods Lecture – Hands on Examples

Question:

Kimmy owns a large country house and adjoining estate in the middle of Hampshire.

Her neighbour, Titus is in the process of building a stable for his collection of horses. The builders arrive and unload the bricks for the construction. They have unloaded some of the bricks past the property line, onto Kimmy’s property. This is a distant corner of the estate which Kimmy rarely ventures over to.

It emerges that Kimmy’s considerable fortune comes from the proceeds of an international drugs smuggling ring. After a protracted police investigation the police arrive to search her property and arrest Kimmy. The police arrive and begin to search the house with a valid warrant.

Kimmy is kept in the dining room of her house, and despite telling the police to get out, they refuse to leave. Two police officers are in the process of searching her house when they come across an ornate vase. One of the officers picks it up to search the inside for drugs. After he has finished searching he decides to prank the other officer. He throws the vase at him and yells ‘catch!’ The officer does not catch the vase which falls to the ground and shatters.

Kimmy hears the smashing vase and goes to see what the commotion is, the officer guarding her stops her from leaving the dining room. She asks him to move but he refuses. She asks he why she isn’t allowed to leave the dining room but he stays silent.

Kimmy is arrested an hour later. Despite Kimmy being of small statute and extremely calm, during the process of the arrest the police officer shouts ‘stop resisting!’ and kicks Kimmy in the back of her knee, leaving her with a bruise.

Kimmy wishes to bring a claim against the police for trespass onto her property (on the basis that she did not give permission for them to enter), for breaking the vase, for false imprisonment in her dining room, and for kicking her in the leg. She also wants to bring a claim against Titus for dumping the bricks onto her property. Finally, the police officer who was hit in the head with a vase wants to bring a claim against his colleague, despite not actually being injured by it.

Answer:

Kimmy’s claim for trespass against the police will likely fail. Whilst Kimmy is the legal possessor of the land, and the police have directly interfered with her rights by refusing to leave when asked, they have the defence of legal authority. Under s.8 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, a search of premises can be authorised under a warrant. Kimmy might have a claim against the officer who broke the vase under this tort. Whilst the officer has a warrant to enter the property for the purpose of searching it, he arguably goes beyond the bounds of the warrant and becomes an unauthorised visitor. Under the principle of ab initio, this would mean that particular officer will be retroactively considered as a trespasser when he stepped onto Kimmy’s land, as per The Six Carpenters Case [1572] EngR 452.

Kimmy is, however, likely to have a claim for trespass to goods for the breaking of the vase. Whilst a warrant has been given authorised a search, it does not give the police carte-blanche to do as they will with Kimmy’s property. Since he has clearly overstepped the bounds of the warrant, the tort of trespass to goods applies, as per s.1(b) of the Torts (Interference with Goods) Act 1977. There is direct interference of a physical nature, distinguishing the facts from Malone v Metropolitan Police Commissioner [1979] Ch 344. There is little question of awareness – the police officer clearly knows what he is doing, hence the joke ‘warning’ to the other officer. Kimmy is therefore entitled to damages from the police officer (which will likely be ascribed to his employer.)

Kimmy also likely has a claim for false imprisonment. Whilst the police of in the process lawfully searching her house, they do not inform her that she is being held in her dining room – this moves the situation from a lawful arrest to an unlawful detention. The facts of this case match those of Murray v Ministry of Defence [1988] 1 WLR 692. The elements of false imprisonment are here: Kimmy is effectively being held in one place, experiences a total loss of freedom (as per Bird v Jones [1845] 7 QB 742.)

The claim for battery will also likely succeed. There is an intentional application of force to another by the police officer. Intention is clear, distinguishing Letang v Cooper [1965] 1 QB 232. Following Cole v Turner [1704] 6 Mod Rep 149, there appears to be some hostility in the actions of the officer in the lack of reasonable provocation. Whilst PACE 1984 provides the police officer with powers of arrest, this does not extend to inflicting unwarranted violence, and so a defence of lawful authority will likely fail. Whilst there also potentially exists an action for assault, since the kick comes from behind it is unlikely that Kimmy has a chance to apprehend the kick before it lands, meaning that the apprehension element of assault is not present.

The claim against Titus for leaving bricks on her property will likely succeed. As per Gregory v Piper [1829] 9 B & C 591 there is a direct interference with Kimmy’s property in the form of the bricks. This is voluntary – distinguishing Stone v Smith [1947] Style 65. Whilst Titus is not aware that he is trespassing onto Kimmy’s property, this will be no obstacle to a claim, as per Conway v George Wimpey & Co Ltd [1951] 2 KB 266.