By Law Teacher

9.1 Defamation, Libel, Slander and Defences – Introduction

Welcome to the first lesson of the ninth topic in this module guide – Defamation, Libel, Slander and Defences! People have an interest in their reputations. Likewise, there is a public interest in the freedom of speech. The tort of defamation attempts to strike a balance in this regard; preventing the publishing of an untrue statement which negatively affects someone’s reputation. There are different types of defamation, and defences to them, and so a comprehensive understanding here is necessary to tackle any problem question here.

At the end of this section, you should be comfortable dealing with defamation, understanding its basic definition as either libel or slander. You will understand the various elements necessary to establish a successful claim in defamation, and also whether any applicable defences could arise.

The section begins by discussing the nature of defamation and the aims of the Defamation Act 2013, a new piece of legislation which aims to consolidate the case law in this area. It discusses libel and slander in turn, and then discusses the individual elements of the tort itself. There is then a comprehensive breakdown of various defences to defamation, before the section concludes with a number of further notes about the nature of the tort.

Goals for this section:

- To be able to apply the legislation and statute pertaining to the tort of defamation to a range of potential factual scenarios.

Objectives for this section:

- To understand the basic definition of defamation and the aims behind the law governing this tort.

- To be able to state and apply the four basic requisite elements of defamation.

- To know the various defences to the tort of defamation, and whether they arise in a range of factual scenarios.

- To be able to apply these rules to a range of different problem scenarios, understanding the rules and peculiar aspects of the tort of defamation.

9.2 Defamation, Libel, Slander and Defences Lecture

Defamation is the act of publishing an untrue statement which negatively affects someone’s reputation. Taken at face value this definition is obviously far reaching. Luckily, both common and statute law has developed a framework to limit the extent of the tort of defamation.

They key authority is the Defamation Act 2013, which helps straighten out the significant body of case law which has built up over the years. The overall aim of the act was to rebalance the law towards protecting freedom of speech.

The same general definition of defamation still applies, but its elements have been slightly recast by the Act. The four primary components of defamation are:

- A defamatory statement;

- About the claimant;

- Which is published; and

- Which has caused or is likely to cause serious harm to the claimant’s reputation.

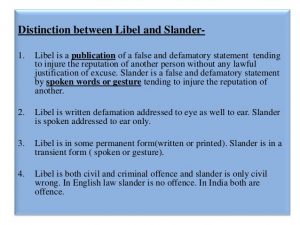

Libel and Slander

Libel and slander are simply two different types of defamation; defamation is the overarching tort, libel and slander are just two different ways of committing that tort. They both remain privy to the general principles governing the tort of defamation.

Libel

Libel refers to permanent defamatory statements, such as that which is written, broadcast, or otherwise performed; s.1 of the Defamation Act 1952; s.28 of the Cable and Broadcasting Act 1984; s.4(1) of the Theatres Act 1968.

The ‘permanence’ requirement doesn’t mean ‘forever’, but rather communication which exists for longer than the time the original message is communicated. Thus, the courts have gone as far as suggesting that skywriting can constitute libel since the writing takes time to disperse, as in Gulf Oil (GB) Ltd v Page [1987] Ch 327.

Words are not necessary; it merely must be a type of permanent communication, Monsoon v Tussauds Ltd [1934] 50 TLR.

It should be noted that libel is also a criminal offence, as well as a tort.

Slander

Slander is a defamatory statement which is non-permanent. The key example is spoken word. Gestures can also constitute slander, since they are a form of non-permanent communication.

Because non-permanent statements have a lesser effect than permanent statements, a claimant must show that they have suffered a ‘special loss’, in effect a loss which can be estimated in monetary terms. The courts however have stretched this definition to include loss of a marriage prospect, Speight v Gosnay[1891] 60 LJQB 231, and loss of consortium, Lynch v Knight [1861] 9 HLC 777.

There are two exceptions to this rule. Firstly, if it is imputed that the claimant has committed a criminal offence punishable by imprisonment, as per Gray v Jones [1939] 1 All ER 798. Secondly, if the statements are calculated to disparage the claimant in his or her profession, business or office, Foulger v Newcomb[1867] LR 2 Ex. 327. It should be noted that the statement must be based on the claimant’s calling, rather than merely being an unrelated statement which nevertheless might affect others’ perception of the claimant’s ability to undertake that calling, Jones v Jones [1916] 2 AC 481; Thompson v Bridges [1925] 273 SW 529.

Slander is not a criminal offence.

Elements of Defamation

(1) The Statement Must Be Defamatory

The definition of a defamatory statement is found in the common law. The general concept can be found through reference to a number of cases.

- The first instance of note is the definition advanced in Parmiter v Coupland [1840] 6 M&W 105 where Parker B defined it as “[a] publication, without justification or lawful excuse, which is calculated to injure the reputation of another, by exposing them to hatred, contempt or ridicule”.

- This definition can be added to that employed in Sim v Stretch [1936] 2 All ER 1237, where Lord Atkin noted that the definition had widened to include words which “tend to lower the plaintiff in the estimation of right-thinking members of society.”

There is no need for a claimant to show that the statement made had a particular effect on certain persons, or the public in general, instead they must simply argue that the defamatory statement would have had the abovementioned negative effect on the claimant’s reputation in the mind of an ordinary, reasonable recipient. This principle is essentially included in s.1(1) of the 2013 Act, which dictates the need to show either serious harm, or likely serious harm to reputation.

As a general rule, statements which are clearly a matter of raised passions or vitriol will not be regarded as defamation, since the ordinary person will usually be held to know the difference between a statement made out of anger and one made calmly, Penfold v Westcote [1806] 2 B & P (NR) 335

With the general definition above in place, the nature of a defamatory can be best understood through its application, as in Byrne v Deane [1937] 1 KB 818 where the difficulty in applying defamation was shown to involve not only evaluating the words used and their context, but also the meaning that might reasonably be given to those words.

The scope of defamation can be seen in a wide range of scenarios. In Berkoff v Birchill [1996] a statement not ordinarily defamatory was held to be so due to the claimant’s profession. In Donovan v The Face [1992] (Unreported) an accusation itself was not defamatory, but the implication was that the claimant was intentionally deceiving the public. See also the case of Cassidy v Daily Mirror Newspapers Ltd [1929] 2 KB 331.

Defamation also need not be particularly insidious, Tolley v Fry & Sons Ltd [1931] AC 333.

(2) The Statement Must Be About the Claimant

It must be established that the defamatory statement is about the claimant. This will usually be simple, if the claimant is named or identified. Sometimes, the exact subject of a statement will be unclear. Nevertheless, if the claimant can be identified from the information included in the statement, then this criterion will be satisfied, as in Morgan v Odhams Press [1971] 1 WLR 1239.

If a statement is made about an individual which is true, but through coincidence also applies to another individual (who can be identified, as per Morgan v Odham Press) for whom it is untrue, then a claim will still exist. This is illustrated by Newstead v London Express Newspaper Ltd [1940] 1 KB 377.

There is a limit to this principle, because there comes a point at which a statement does not refer to identifiable individuals, but to a class of persons. This can be seen in Knuppfer v London Express Newspapers [1944] AC 116. The claim here, failed – there was nothing in the article personally identifying the claimant.

There thus exists a vague point at which a reference to a class becomes a reference to identifiable individuals. This can be seen in Le Fanu v Malcolmson[1848] 1 HLC 637.

(3) The Statement Must Be Published

As noted above, defamation is about communication of a statement. This is referred to as publication, although this term has a specific legal meaning. The definition can be found in Pullman v W. Hill & Co Ltd [1891] 1 QB 524. Lord Esher MR provided that “[t]he making known of the defamatory matter after it has been written to some person other than the person of whom it is written”. Intention is also necessary.

If it is reasonably foreseeable that a third party will read or receive a defamatory statement which is sent directly to the claimant, then that will constitute publication, as in Theaker v Richardson [1962] 1 WLR 151. See the case of Huth v Huth [1915] 3 KB 32 to demonstrate a lack of requisite foreseeability.

(4) The Statement Must Cause Serious Harm

This criterion is a new development, brought into force by s.1 of the 2013 Act. Although the case law on this point is sparse, there exists one noted case, in the form of Cooke v MGN Ltd [2014] EWHC 2831.

Defences

Truth

As per s.2(1) of the 2013 Act, if a statement is true, then this will form a complete defence. It should be noted that the burden of proof for showing that a statement is true rests with the defendant. The defendant does not have to show that every single characteristic of the statement made is true, merely that it is substantially true. This can be seen Alexander v North Eastern Railway Co [1865] 6 B & S 340.

Privilege

Individuals in certain roles are protected from defamation claims. This takes two forms; the first being absolute privilege. This is enjoyed by Parliamentarians (as per the Bill of Rights 1668) and members of the judiciary (as per s.14 of the Defamation Act 1996).

The second is qualified privilege, as per s.15 of the 1996 Act, and covers situations in which an individual is obliged morally or statutorily to communicate information. Whilst an inaccurate reference can be damaging, it will not give rise to a defamation claim here. The exception is if a reference is made maliciously (as per Spring v Guardian Assurance plc [1994] UKHL 7.)

Public Interest

As per s.4 of the 2013 Act, if a statement is made on a matter of public interest, and the defendant reasonably believes that publishing the statement is in the public interest. Although there is little guidance on what exactly constitutes public interest since 2013, Reynolds v Times Newspapers Ltd [2001] 2 AC 127 provides a list of the factors which indicate whether a statement is made in the public interest or not:

- Seriousness;

- Subject matter;

- Source;

- Verification;

- Status;

- Urgency;

- Comment from the claimant;

- Balance;

- Tone; and

- Circumstances.

In essence, the courts are seeking to make a distinction between diligent, proper journalism published in good faith, and disingenuous editors attempting to use the public interest defence to protect poor quality, salacious reporting.

Honest Opinion (Or ‘Fair Comment’)

As per s.3 of the 2013 Act, honest opinion will not be considered defamation. The key to advancing this defence is that the statement must be presented as opinion, rather than fact, and that the statements made are ones which are actually matters of opinion, rather than fact.

The opinion must also be one which the court regards as one which a reasonable person might form based on the facts available to them – so conjecture which ignores obvious evidence to the contrary will not be protected by this defence.

Reportage

As per s.7 of the 2013 Act, there are a variety of situations in which simply reporting what another has said will be protected from defamation claims. This is based on the distinction between republishing a statement, and merely reporting that a statement has been made.

Website Operators

As per s.5 of the 2013 Act, a website owner can defend itself from defamation claim by simply pointing out that the statement was not one they made, but instead it was one made by a user.

A claimant can defeat this defence if they show that it was impossible for them to identify the original author of the statement. Thus if a website operator provides users with absolute anonymity, then it will be held responsible for the content posted there. A claimant can also defeat this defence by showing that they asked the website operator to remove the defamatory statement, but that they failed to do so.

Further Notes

The Dead Can’t Be Defamed (or Defame)

Although the tort is one of injuring reputation, this only applies to the reputations of the living.

Trial by Jury (with Permission)

There exists the ability for a defamation claim to be heard by a jury. This used to be a right, but s.11 of the 2013 Act has removed it, allowing a trial by jury if ordered by a court. The willingness of the courts to do this is doubtful, considering the added cost, time, and unreliability this would add to any given case.

Limitation Period

The limitation period for claims for defamation is unusually short, lasting only a year in time from when the statement occurred as per s.4A of the Limitation Act 1980. If a statement is made and then repeated (in a form which is substantially the same), then this time limit starts upon the first instance of publication, as per s.8 of the 2013 Act. This does not apply to publication in a materially different form.

Company Reputation

Unless the harm is of a serious financial nature, organisations which trade for profit cannot bring a claim for defamation, as per s.1(2) of the 2013 Act.

9.3 Defamation, Libel, Slander and Defences Lecture – Hands on Examples

Question:

Xander owns and runs a large medical research facility (XandCorp, a publically traded entity) which as part of its work tests pharmaceuticals on rats. This makes both the organisation and Xander unpopular with a number of animal rights campaigners.

Willow is an animal rights campaigner. Whilst she is running errands in town she sees Xander and recognises him. In a fit of rage she screams at him “Murderer! Destroyer of tiny fluffy lives!” A number of people hear this outburst.

Willow writes for a large national newspaper, and decides to write an article about XandCorp. In it, she asserts that Xander is engaging in widespread embezzlement within the company, taking money from the pension fund. This is untrue, having been invented by Willow.

Finally, she writes another article for an online blog, stating that under Xander’s leadership, XandCorp has been given a ‘C-’ rating during its last animal welfare inspection. This is an honest mistake: XandCorp was actually given a C+. This information has already been published on the rating body’s website.

Advise Xander on any defamation claims that might arise from Willow’s actions.

Answer:

The first event is that of Willow’s outburst on the street, which is potentially slanderous (since it is a non-permanent statement.) It is worth noting, first of all, that Xander will not need to demonstrate special loss, since the accusation is that Xander has committed a crime punishable by imprisonment – namely, murder, as per Gray v Jones [1939] 1 All ER 798.

The four elements of defamation are a defamatory statement, about the claimant, published, and which causes, or is likely to cause, serious harm.

The defamatory nature of the statement is questionable. Under Parmiter v Coupland [1840] 6 M&W 105 and Sim v Stretch [1936] 2 All ER 1237 the definition of a defamatory statement is one “calculated to injure the reputation of another” or one which will “tend to lower the plaintiff in the estimation of right-thinking members of society”. Whilst the accusation fulfils these criteria on paper (being thought of as a murder is damaging), in the context it is arguably unlikely that the witnesses will actually believe that Xander is a murderer walking around freely. Under Penfold v Westcote [1806] 2 B & P (NR) 335 the vitriolic nature of Willow’s statements mean that it is unlikely that they will be regarded as defamatory; people can be expected to know when an accusation is serious, and when it is a matter of mere anger.

The statement is about the claimant (it is yelled directly at him.) It can be regarded as published, since at least one third party has heard it (and this is obviously foreseeable), as per Pullman v W. Hill & Co Ltd. [1891] QB 524. The serious harm criterion is difficult to establish – there is no indication that apart from some public embarrassment that Willow’s statement was injurious to Xander. This claim will likely fail.

The second event is that of Willow’s newspaper article, which is potentially libellous. The same four criteria apply. The defamatory nature of the statement is clear – an assertion that the owner and manager of a publically traded company is embezzling funds will have a serious effect on the reputation of the concerned individual. This is both an accusation of criminal activity, and of dishonesty (as seen in Donovan v The Face [1992] (Unreported)). It is also an accusation of professional impropriety, as in Tolley v Fry & Sons Ltd [1931] AC 333.

The statement is directed at Xander, and so it can be assumed that the identifiability standard of Morgan v Odhams Press [1971] 1 WLR 1239 has been met. It has been published. It can be argued that the assertions are likely to cause serious harm to Xander and his company. Such accusations both harm Xander’s ability to work (since they cast aspersions on his honesty), and since they relate to his company, can potentially do serious economic harm.

Willow might attempt to advance a public interest defence under s.4 of the Defamation Act 2013. This is backed up by the fact that she is acting as a journalist, as in Reynolds v Times Newspapers Ltd [2001] 2 AC 127 (although it should be noted that the case is merely persuasive, since the Reynolds defence has been abolished under s.4(6).)

Following Lord Nicholl’s list of factors favouring the use of the defence in Reynolds, it can at least be said that the subject matter is of interest to the public – objectively, embezzlement is a topic which could be expected to be a suitable topic for a newspaper to cover.

However, this is the only feature of the article which will aid Willow’s use of the defence. To the contrary, the accusations are very serious, and are unsourced and unverified. The statement is not based on any already published reliable information, lacks comment from the subject and has no semblance of balance. It appears that the tone is one of stated fact, rather than speculation. There is nothing to indicate that it was necessary to rush the allegations into publication without checking them. Thus, in line with the judicial reasoning in Reynolds, the public interest defence will likely fail, and the claim for defamation will likely succeed.

Finally, there is the blog article. Assuming the blog operator is willing to identify Willow as the author, she will be the proper defendant (as per s.5 of the 2013 Act.) The statement is defamatory – a poor animal welfare rating will be damaging to Xander’s reputation. The statement is about Xander’s leadership, and is published. The serious harm aspect can be doubted, however. Considering that there is already information circulating that Xander was given a C+ (a middling grade), a false statement that Xander was given a slighter lower middling grade cannot really be argued to be seriously harmful.

Furthermore, Willow can advance a truth defence, under s.2(1) of the 2013 Act. Whilst the statement is technically untrue, Willow might be able to argue that the substance of the remark remains truthful. This can be likened to Alexander v North Eastern Railway Co [1865] 6 B & S 340, where a technical falsehood was regarded to be substantially true since it roughly matched the truth of the situation. Just as there is little material difference between a prison sentence of two weeks versus three weeks, there is little material difference between a grade of C- and C+ (at least from the facts at hand.) This claim will likely fail.