By Law Teacher

12.1 Remedies – Introduction

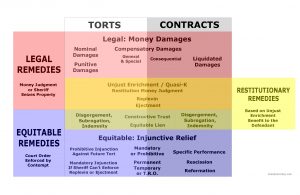

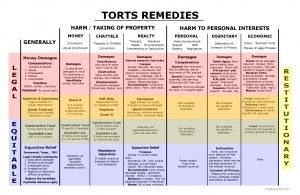

Welcome to the first lesson of the twelfth topic in this module guide – Remedies! The main remedies in tort are injunctions, which compel a defendant to act in a certain manner, and damages, which are compensatory and intended to restore to the claimant what he has lost. An understanding of the scope and applicability of certain remedies will be important to a range of different problem scenarios.

At the end of this section, you should be comfortable understanding the different types of damages and injunctions that can be awarded to a successful claimant. This section begins by breaking down the aims and objectives of damages, and going into depth about the kinds of damages that can be awarded, and how they are quantified. There is then a comprehensive overview of the types of injunction that may be awarded, and in what circumstances they will be successfully applied for.

Goals for this section:

- To understand how and when the courts may award certain remedies to a successful claimant.

Objectives for this section:

- To understand the different types of damages available to a claimant, how they are quantified and what principles are relevant in their application.

- To be able to define the various types of injunction and to know when they may be available to a claimant.

12.2 Remedies Lecture

Once a case has been made by a claimant and the defendant’s case defeated, the court will decide on an appropriate remedy to apply to the problem at hand. Remedies come in two primary forms: damages and injunctions. The outcome is ultimately determined by the court.

Damages

Damages are quite simply the award of a monetary sum to the claimant, which must then be paid by the defendant. The general guiding principle is that of full compensation: the idea that the amount of damages awarded should return the claimant to the position they would have been in had the tort not occurred.

An award of damages is made up of a number of different smaller awards which take into account different elements of the case, all added together to reach a final lump sum. Prudent judges will provide this breakdown a trial.

The Mitigation Principle

The mitigation principle is, roughly, that a claimant must act where reasonable to mitigate their own losses. This is important because the cost of many of heads of damage could be artificially inflated by an avaricious or malicious claimant.

Special Damages

The first category is special damages. That is, damages which can be specified at the time of the trial (so damages for injuries or costs which take place pre-trial).

- Injuries are quantified using the Ogden tables – essentially a guide for judges and lawyers to help them calculate the appropriate amount for a given injury. As per the mitigation principle, a claimant will be expected to take reasonable care to not make their injury worse than it already is.

- Loss of earnings before the trial come under special damages.

- Pre-trial medical expenses are included under special damages. It will be up to the claimant to demonstrate that their medical expenses have been reasonable. This principle can be seen in Donnelly v Joyce [1973] QB 454 where the courts held that a mother who quit her job to care for her injured son could claim for her wages as damages. Since a ‘reasonable cost’ was that of a nurse, and the mother’s lost wages were less than this amount, the cost of the lost wages was recoverable.

This also demonstrates the compensation principle – the relevant cost is the one incurred, rather than the one that the claimant is entitled to. Thus the maximum recoverable cost is that which is reasonable, or that which the claimant incurred, whichever is less.

Claimants are not necessarily expected to be complete spend-thrifts, as long as they can demonstrate that their choice of treatment is reasonable, Rialas v Mitchel [1984] 128 SJ 704. What is reasonable for a particular claimant will depend on their circumstances, and this can lead to some novel decision making, Roberts v Roberts [1960] (The Times, 11 March).

Notably, whilst the most obvious thing a claimant could do to mitigate costs would be to opt for NHS treatment, the courts are instructed by statute to ignore this option when considering whether the claimant’s behaviour has been reasonable, as per s.2(4) of the Law Reform (Personal Injuries) Act 1948.

- House help will often be necessary for those who have suffered a debilitating injury. Thus a claimant can table the costs of help to accomplish these tasks under special damages, Daly v General Steam Navigation Co Ltd [1981] 1 WLR 120. It should be noted that it is common for claimants to soldier on and perform their own domestic tasks – if this is the case, a claimant will be able to recover general damages which take into account loss of amenity and if performing such tasks causes pain, damages which account for pain and suffering.

The law has developed a particular way to deal with situations in which outside assistance is provided by family of friends. This is in order to take account of the fact that often such help won’t be easily quantifiable. This method of quantification can be seen in Evans v Pontypridd Roofing Ltd [2001] EWCA Civ 1657 where the courts acknowledged the fact that it would be unjust to quantify familial caring at a commercial rate, and instead stated that the amount should be reduced by 25% to reflect the non-commercial nature of the care. Whilst the court provided this method of quantification, it also noted that this was not binding.

- Personal expenses might rise as a result of injury. These can thus be claimed for. Examples include additional heating for a claimant who becomes more perceptive to the cold, as in Hodgson v Trapp [1989] AC 807. It is important to note that the defendant is only liable to the extent that the cost is in addition to the claimant’s usual spending.

- Finally, the claimant might have suffered easily quantifiable property damage. These damages are as much subject to the mitigation principle as any other.

It is worth noting that claimants will often look to expert evidence in order to argue why their behaviour or needs are reasonable. Similarly, a defendant might bring their own expert to argue that the claimant has acted unreasonably, in order to reduce the award of damages.

General Damages

General damages are those which cannot be quantified at the time of trial, and instead are more prospective in nature. The court will ask the claimant to demonstrate what their likely future costs and losses are likely to be. Some injuries are lifelong, and thus will have a lifelong cost. These are far more difficult to quantify accurately. It should be noted that all of these calculations will involve hypothetical assessments of an individual’s remaining lifespan, which in itself is precarious.

- Future loss of earnings forms a substantive part of general damages. A claimant who cannot work at all will be able to recover their earnings for the length of their future career, up until a likely retirement date. Sometimes a claimant will be prevented from carrying on with their current career, but will be able to undertake some other sort of work. Claimants don’t have to work, but the court will imagine that they will in calculating their damages; in other words, claimants are expected to mitigate their future losses.

Promotions create a significant difficulty. As long as the claimant can show to the court that they were on a career ladder of sorts (which they were likely to ascend) they will be able to claim higher damages to reflect career advancement, as in Brittain v Garner [1989] (The Times, 18 Feb).

- Future medical expenses also come under this category, since they will often be speculative. The mitigation principle applies here as elsewhere, so the claimant will have to argue that they are intending to pay for a reasonable course of medicine, Lim Poh Choo v Camden and Islington AHA [1980] AC 174.

Again, the ‘no-NHS’ principle applies here, but the claimant will still need to argue that they will be using private medical facilities, rather than the NHS. This argument is not difficult to make, however, Woodrup v Nichol [1991] PIQR 104.

It is important to note that just because an activity might help with a negligently acquired injury, this does not mean that it can necessarily be wrapped into damages – it must be demonstrated that the activity is an additional cost. This principle can be found in Cassell v Riverside Health Authority [1992] PIQR Q168.) Similarly, rehabilitation activity must be undertaken in a reasonable manner, Robshaw v United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust [2015] EWHC 923.

- Pain and suffering are a general damage, since they cannot be quantified in an exact manner. Their exact calculation will depend on the claimant and the manner of their injury. It should be noted that pain and suffering is subjective. An example of this thinking can be seen in H West & Son Ltd v Shepherd [1963] UKHL 3. However, that the courts will not consider economic or social position to have a bearing on this category, as per Fletcher v Autocar and Transporters [1968] 2 QB 322.

This category also includes psychiatric harm, as per James v Woodall Duckham Construction Co Ltd [1969] 1 WLR 903, but in keeping with tort law’s approach to psychiatric injury, does not include mere sorrow or grief, as per Kralj v Kaye [1986] 1 All ER 54.

- Loss of amenity is also a type of general damage, referring to the physical impairments (and loss of ability to undertake activities) that can occur as the result of an acquired injury. This definition can be found in H West & Son Ltd v Shepherd [1964] AC 326. Loss of amenity is based on working out what exactly the claimant has lost out on. Examples of such losses include loss of ability to fish, as per Moeliker v A Reyolle & Co Ltd [1977] 1 All ER 9, disfigurement in Oakley v Walker [1977] 121 Sol Jo 619, or loss of senses in Cook v JL Kier and Co [1970] 1 WLR 774.

Nominal Damages

Nominal damages are a small financial award awarded when a claimant’s rights have been infringed, but little to no harm has occurred. They are often awarded alongside an injunction. Of course, aggravated or serious attacks on a claimant’s rights will result in higher (and thus non-nominal) awards of damages, as per Alexander v Home Office [1988] 1 WLR 968.

Contemptuous Damages

Where the courts are of the belief that a claim technically has legal merit, but little moral merit, then they will award contemptuous damages to the claimant. This is often as small of an amount as possible. Contemptuous damages can be seen in Reynolds v Times Newspapers [1998] 3 WLR 862.

Aggravated Damages

Aggravated damages are those reflecting the fact that a case has been aggravated by one factor or another, usually for humiliation or distress caused to the claimant. This can be seen in Appleton v Garrett [1996] 5 PIQR P1 where the court saw fit to extend this category of damages to those emotions felt by the claimants in the case at hand.Thus aggravated damages allow the court to take account of abstract injury to the claimant’s feelings (as long as the claim itself is based on something more concrete.)

Exemplary Damages

Exemplary damages are similar to aggravated damages, but rather than stemming from injury to the claimant’s feelings they stem from the defendant’s own poor behaviour, with the aim of making an example of their conduct. This can be seen in Thompson v Metropolitan Police Commissioner [1998] QB 498.

Payment

Originally, the only option open to the courts was lump sum payments at the time of the judgement. The Damages (Variation of Periodical Payments) Order 2005 was passed, which allows the court to rule that damages should be paid periodically, and then reviewed upon the deterioration or improvement of the claimant’s injury.

Although there was a point at which certain judges would award extra damages to account for inflation, this is now not the case. It is assumed that claimants will have the foresight to invest or save their lump sum in a way which will deal with inflation (via interest rates or similar).

Injunctions

An injunction is a declaration by a court that the defendant must behave in a certain manner. They come in two main forms – prohibitory, in which a claimant is prohibited from doing something and mandatory, in which the defendant must do something. As well as being either prohibitory or mandatory, injunctions will be either quia timet, final, or interim.

Injunctions are a matter of court discretion. Whilst damages are available to claimants in all eventualities, injunctions are an equitable remedy, and thus whether they are granted depends on the will of the court. Their use tends to be limited, since they involve essentially overriding the will of an individual or organisation.

Prohibitory Injunctions

Prohibitory injunctions are useful to prevent the interference with a claimant’s rights. The tendency is to grant an injunction where there is a good chance of the tortious behaviour being repeated, Wollerton and Wilson Ltd v Costain Ltd [1970] 1 WLR 411.

The courts won’t always grant an injunction if the tortious behaviour is trivial, or if the defendant is not at fault. This can be seen in Armstrong v Sheppard and Short Ltd [1959] 1 QB 384 where the interference was trivial, and the claimant had effectively consented to the trespass, meaning that the defendant could not be described as being at fault.

Mandatory Injunctions

Mandatory injunctions tend to be rarer, firstly because cases tend to arise more often from people doing something they shouldn’t (so call for prohibitory injunctions), and secondly because mandatory injunctions involve a greater level of interference with the defendant. This can be seen in Redland Bricks Ltd v Morris [1970] AC 652 where the court allowed an appeal against a mandatory injunction because the costs of doing so were disproportionate. The court identified four criteria which should be satisfied before a mandatory injunction would be granted:

- Firstly, there must be a strong possibility of damage occurring in the future.

- Secondly, damages must be an insufficient alternative.

- Thirdly, the defendants must have behaved unreasonably.

- Fourthly, the injunction must be capable of describing exactly what the defendant should do.

Further Injunction Subtypes

Injunctions can also be divided up into three groups, depending on a when tortious event is likely to occur: quia timet injunctions, final injunctions and interim injunctions.

- Quia timet (‘because he fears’) injunctions are used when the claimant fears a tortious action will occur, but it has not yet taken place. The prerequisites which must be fulfilled before they are granted were also mentioned in Redland Bricks: there must be evidence that the defendant is intending to take an act; that act must be one which will cause significant irreparable damage to the claimant; and there must be evidence that the defendant will not desist unless a quia timet injunction is granted.

- Final injunctions are simply those which are granted after a tort has been committed, but where it is likely that the tort will reoccur.

- Interim (or interlocutory) injunctions apply whilst the tortious activity is ongoing (or else where there is a high chance of it reoccurring in the near future). By definition, they are temporary. Their use is particularly restrained, since they are essentially a remedy which is applied before a case has been properly heard. The criteria for an interim injunction are found in American Cyanamid v Ethicon [1975] AC 396 where the court laid down a two-part test to be met:

- The first part of the test involved the claimant showing that the issue at hand was serious enough to warrant an interim injunction.

- The second part of the test involves the claimant demonstrating that, on the ‘balance of convenience’, it would essentially be more sensible for the court to grant the interim injunction.

Equitable Rules

Since injunctions are an equitable remedy, they are affected by the principles of equity law. Whilst such a wide topic cannot be covered here, there are three rules it is useful to know. Firstly, equity does not act in vain. Secondly, equity looks poorly upon delay. Thirdly, equity looks for claimants with clean hands.