By Law Teacher

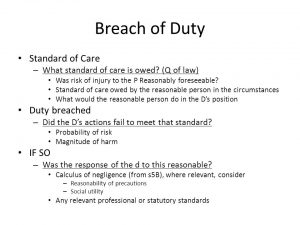

What standard of care is owed? (Q of law) Was risk of injury to the P Reasonably foreseeable? Standard of care owed by the reasonable person in the circumstances. What would the reasonable person do in the D’s position. Duty breached. Did the D’s actions fail to meet that standard? Probability of risk. Magnitude of harm. IF SO. Was the response of the d to this reasonable? Calculus of negligence (from s5B), where relevant, consider. Reasonability of precautions. Social utility. Any relevant professional or statutory standards.

2.4.1 Breach of Duty: The Standard of Care – Introduction

Welcome to the fourth lesson of the second topic in this module guide – Breach of Duty; The Standard of Care. The breach of a duty will appear as one aspect of any larger negligence problem, and is a factual or evidence-based inquiry.

At the completion of this section, you should be comfortable in being able to identify an appropriate standard of care, and deciding whether the defendant breached that standard. You will understand that the general standard of care is objective, and is normally ‘the reasonable person’ standard, though there are exceptions to this rule.

This section begins by explaining that the standard of care is a test based in reasonable foreseeability, before discussing how to ascertain the standard of care for different defendants. Within this is a discussion of particular types of defendant who attract particular standards. The section goes on to clarify the reasonable standard of care, as it may vary according to a number of factors, such as the nature of the defendant or the activity being undertaken. Finally, the section discusses the process of proving a breach on a balance of probabilities.

Goals for this section

- To identify the appropriate standard of care.

- To establish whether the defendant has breached that standard.

Objectives for this section

- To be able to establish what standard of care applies.

- To understand that the general standard is the objective ‘reasonable person’ standard, but that there are exceptions to this rule.

- To understand how this standard may shift according to the magnitude of risk, the cost of precautions available and the social value of the activity.

- To understand the process of proving breach, including via res ipsa loquitor and in cases involving criminal proceedings

2.4.2 Breach of Duty Lecture

Once a duty of care has been found, it is then necessary to ask whether the defendant has acted in such a way as to have breached that duty of care. The key thing to ascertain is the standard expected of the defendant and then to examine the actions of the defendant to see whether they have fallen short of this standard.

The standard of care will always be based on reasonable foreseeability. This means that the courts will not ask the defendant whether they foresaw a certain outcome or not, but rather they will seek to work out what the defendant ought to have foreseen. This means that cases which involve highly unlikely outcomes are not likely to be successful. In Fardon v Harcourt-Rivington [1932] All ER Rep 81 the courts ruled the outcome was a ‘fantastic possibility’, and therefore not foreseeable. The defendant was only obliged to avoid ‘reasonable probabilities’.

Ascertaining the Standard of Care for Different Defendants

The law strikes a balance between providing compensation where a failure has been particularly egregious, and where a genuine accident has occurred. As such, Donoghue v Stevenson(and subsequent cases) have held defendants to the standard of the reasonable man. If a defendant has acted reasonably, then they will not have breached the duty of care, and vice versa. Although this seemingly suggests that defendants are always judged against objective standards, there does exist some scope to alter the test, depending on the characteristics of the defendant.

The general rule is that defendants are expected to act with a reasonable level of skill in the activity they are undertaking. Consider the leading case of Nettleship v Watson where the defendant argued that as a learner driver, she should be judged against a lower standard of care. The courts rejected this, and held that some who undertakes a task should be judged against the standard of a reasonably qualified, competent person undertaking that task.

In essence, this means that a defendant cannot rely on their own lack of skill or knowledge as a defence. The most important general principle regarding breach is therefore that the applicable standard of care is that of a reasonably competent person undertaking that activity.

In Hall v Brooklands Auto-Racing Club[1933] 1 KB 205 the ‘reasonable man’ was described as ‘the man in the street’ or ‘the man on the Clapham Omnibus’. Essentially, the reasonable man should not be considered as acting perfectly, merely, averagely.

There are a number of exceptions to the general rule, as follows.

Defendants with Certain Medical Conditions

The courts have held defendants to a standard which takes into account certain medical conditions a defendant might be suffering from. In Mansfield v Weetabixthe standard of care expected of a lorry driver with an undiagnosed condition was “obliged to show in these circumstances was that which is to be expected of a reasonably competent driver unaware that he is or may be suffering from a condition that impairs his ability to drive. To apply an objective standard in a way that did not take account of [his] condition would be to impose strict liability…” (Leggatt LJ, at 1268).

Children

The standard is instead that of an ordinary child of the defendant’s age as per Orchard v Lee[2009] EWCA 295. In the case, the courts ruled that no breach had occurred as the 13-year-old involved was acting in the usual manner expected of a 13-year-old.Children are not able to escape all liability – thus, in Mullin v Richards[1998] 1 WLR 1304 the courts considered that an incident was reasonably foreseeable to a 15-year-old.

Sporting Events

In Woolridge v Sumner[1963] 2 QB 43 it was held that due to the inherent risks involved in sporting activities – they often involve moving faster or more violently than would ordinarily be expected of an individual – the standard is different.

Participants must still act in a manner reasonably expected of someone playing that sport. In Caldwell v Maguire[2001] EWCA Civ 1054 the courts noted that whilst the standards of behaviour which apply in sporting situations are lower than those which might apply in everyday life, sporting competitors are still expected to act in a reasonable manner – both in terms of following the rules of a sport and in terms of acting with skill and aptitude.

Those Acting as Professionals

Professionals are judged against the standards of their profession. This is based on the Bolam test: those acting as professionals are expected to act in accordance with a competent body of professional opinion. Although Bolam involved medical practitioners, it has been held to apply in general to other professionals. This has also involved widening the test to take into account non-traditional professions such as auctioneers (Luxmoore-May v Messenger May Baverstock[1990] 1 WLR 1009) and window designers (Adams v Rhymney Valley DC[2000] Lloyd’s Rep PN 777).

A clarification per Bolitho v City and Hackney Health Authority[1998] AC 232 is that a course of action must be capable of withstanding logical analysis before it is protected by the Bolam test.

Clarifying the Reasonable Standard of Care

The relevant standard of care shifts depending both on the nature of the defendant, and the nature of the activity being undertaken.

Magnitude of Risk

If a risk is particularly pronounced, then there will be an expectation that the reasonable person will act to prevent that risk from occurring, as per Bolton v Stone[1951] AC 850 and Miller v Jackson[1977] QB 966. The law will seek to impose a standard of care which scales proportionally with the risk involved.

If a risk is of a serious harm, the applicable standard of care may be higher due to such a risk being foreseeable (Paris v Stepney Borough Council[1951] AC 367).

Cost of Precaution

The courts will take into account the cost of precaution when considering the applicable standard of care. The lower the cost of a precaution, the more reasonable it will be held for the defendant to have taken it, and vice versa (Latimer v AEC Ltd[1953] AC 643).

Therefore, when dealing with a risk, an inquiry should be made regarding the cost of prevention. However, it should be noted that it is unlikely that a defendant will be able to use lack of money as a defence. After all, safety is usually the first concern we’d like businesses and organisations to deal with, rather than financial viability.

Social Value of Activity

The courts will apply a lesser standard of care to socially valuable activities, and vice versa. This principle is best understood via the relevant leading case, Watt v Hertfordshire County Council [1954] 1 WLR 835, where the courts denied the claim of a fireman injured in the course of a rescue; the emergency nature of the situation and the utility of saving a life outweighed the need to take proper precautions.

It should be noted that even when the social value of an activity is extremely high, there still exists a need to act with relative diligence. Contrast Watt (above) to Ward v London County Council[1938] 2 All ER 341, where the courts held that a fire engine slowing down sufficiently at the junction would not have substantially affected the service’s emergency response, and that the social value of the fire service’s activities did not justify needlessly endangering other road users.

The social value of a given activity is dependent on the context of that activity. In Scout Association v Barnes[2010] EWCA Civ 1476 the courts were left to ascertain whether a chance of injury in a game played in the dark at the Scout Association was in proportion to the social value of the activity. The courts ruled that whilst there was additional value in playing the game in the dark, this turned an ordinarily risky, but socially justified activity, into one which could not be justified by reference to social value. Thus, an activity which ordinarily didn’t breach standard of care became unacceptable when the context changed.

Proving Breach

Once the relevant standard of care has been established, it is up to the claimant to argue that the defendant breached the standard. This will be based on the balance of probabilities.

Res Ipsa Loquitor

Translated as ‘the facts speak for themselves’, this refers to specific situations in which the claimant cannot directly show that the defendant factually acted in a negligent manner, but that it is more likely than not that the defendant acted negligently. In Scott v London & St Katherine Docks Co[1865] 3 H&C 596, the courts ruled that there was no need for the claimant to show that the defendants had factually caused his injuries on the basis of res ipsa loquitor, laying down a three-part test for the use of the maxim.

Firstly, the thing which causes damage must be under the control of the defendant (or under the control of someone for whose actions the defendant is responsible for.) Secondly, the cause of the accident must be unknown. And thirdly, the injurious event must be one which would not normally occur without negligence.

Each part of this test can be clarified further. The definition of ‘control’ depends on the case itself. In Easson v LNER[1944] 2 KB 421 it was held that a train company could not be described as being in control of the doors which injured the claimant as there was no evidence that the train company had opened the door; it could just have easily have been a passenger on the train who opened it.

The need for an unknown cause is relatively self-explanatory. If the facts of the case are available to the court, then the claimant can rely on them to prove his or her case in fact, rather than relying on res ipsa loquitor. In Barkway v South Wales Transport[1950] AC 185, it was held that where two separate versions of events are presented to the judge, he cannot use the res ipsa loquitor mechanism – the judge must make a decision regarding the most accurate set of facts.

Finally, it must be successfully argued that the event which caused the claimant’s injuries would not have occurred without some sort of negligence. Scott(above) demonstrates this, as does Ward v Tesco Stores Ltd[1976] 1 WLR 810 where the courts held that an accident would not have occurred but for some negligence on the part of the defendant, and so res ipsa loquitor applied.

The effect of res ipsa loquitor is that it raises a presumption of negligence against the defendant. However, this presumption is rebuttable – if the defendant can still provide an explanation of how the harm might have occurred without negligence then the use of the maxim will fail. This will leave the claimant to show that the defendant’s version of events is faulty – in essence the burden of proof is then the same as a normal case.

Cases Involving Criminal Proceedings

Finally, it is possible for a claimant to use a defendant’s criminal conviction as proof that an act of negligence occurred, as per the Civil Evidence Act 1968:

s.11 Convictions as evidence in civil proceedings

(2) In any civil proceedings in which by virtue of this section a person is proved to have been convicted of an offence by or before and court in the United Kingdom or by a court-martial there or elsewhere […]

(a) he shall be taken to have committed that offence unless the contrary is proved.

If a defendant is convicted of an offence, and that offence involves a negligent action, then the burden of proof will be on the defendant to show that their conduct was not negligent. This is most relevant in cases involving traffic accidents – careless driving is both a criminal offence, but is also an act which will often give rise to cases in tort. Rather than claimants having to prove negligence on the part of the defendant, they can simply refer to the fact the defendant has been found criminally liable for a negligent act.

2.4.3 Breach of Duty Lecture – Hands on Example

Question 1:

The Hawkins Laboratory is undertaking research on a weaponised strain of the common cold. This research is defensive in nature – the lab seeks to prevent the use of the common cold as a bio-weapon. As a result, the lab works with a number of dangerous samples of the virus.

One day, a breach in containment leads to an outbreak in a nearby town, killing several residents.

The residents bring a case against the laboratory. In the course of the investigation, it is found that the breach was ultimately caused by a lack of maintenance of the lab’s decontamination system. Although the lab was aware of the issue, it did not fixed it, citing the exorbitant cost of hiring a decontamination consultant as the reason.

Identify the factors which the court will use in determining the applicable standard of care for Hawkins Laboratory. Do not discuss the doctrine of Rylands v Fletcher.

Question 2:

Jonathan and Dustin are participating in a charity car race.

Jonathan has only just passed his driving test, and so is unsure on the road. He fails to realise he is in the wrong gear at the start of the race, and accidentally reverses, crushing the foot of a spectator standing behind him.

Dustin is a relatively competent driver. However, unbeknown to Dustin he has an undiagnosed case of narcolepsy, and so is prone to under-going ‘micro-sleeps’: moments when Dustin temporarily blacks out and reawakens a second or two later. Dustin suddenly falls into a micro-sleep at the end of the race and when he re-awakes, he finds he has crashed into the podium, utterly destroying it.

Both drivers have cases brought against them.

Identify the individual characteristics of the drivers which will affect the standard of care applied to the defendants at trial.

Answer 1:

The courts will broadly consider three different factors in ascertaining the expected standard of care: the magnitude of the risk involved, the cost of taking precautions, and the social value of the activity involved.

In terms of the magnitude of risk involved, this depends on two factors: the likelihood of a risk occurring, and the potential seriousness of that risk once it manifests.

The likelihood of the risk occurring in the case of Hawkins Laboratory is low, and this means the applicable standard of care will also be lowered – as per Bolton v Stone [1951] AC 850 (and twin-case Miller v Jackson[1977] QB 966), the lower the risk, the lower the applicable standard of care will be. In the case of Hawkins lab, it is dealing with a less likely risk, rather than a more likely risk. It can therefore be favourably compared to Bolton, and distinguished from Miller.

However, the seriousness of a containment breach is relatively high – as demonstrated by the deaths caused by the breach. As per Paris v Stepney Borough Council[1951] AC 367, a higher standard of care applies when the risks involved are heightened. The risks presented by the lab’s work is high, and therefore so will the standard the care be.

The cost of taking precautions will also affect the applied standard of care. As per Latimer v AEC[1953] AC 643, defendants are not mandated to act perfectly, they must only take reasonable precautions against risk. Whilst the Lab cites cost as a reason it did not properly maintain its decontamination equipment, this is unlikely to have a material effect on the expected standard of care – it is reasonable to assert that a bio-weapon lab should have suitable decontamination equipment, even if this comes at some cost.

Finally, the social value of the activity undertaken will affect the applicable standard of care, as in Watt v Hertfordshire CC[1954] 1 WLR 835. The work of the lab appears to be socially valuable – it is, after all, aimed towards protecting lives. This means that the standard of care expected of the lab will be lower.

In summary, whilst the lab is dealing with an unlikely risk, it is a serious one. Whilst pre-emptively acting to prevent the containment breach would have been expensive, it is arguably reasonable to demand a bio-lab takes sufficient precautions when dealing with a deadly virus. There is a distinct utility to the actions of the lab, but this does not justify its negligent lack of maintenance – the social utility of its actions would still exist had the lab properly repaired its decontamination system.

Answer 2:

Although Jonathan is a newly qualified driver, his inexperience will not act as a defence. Under Nettleship v Watson[1971] 3 WLR 370, Jonathan is expected to act with a reasonable level of skill in the activity he is undertaking. This standard will not change just because Jonathan had only just learned how to drive. As such, Jonathan is likely to be found to have breached the applicable standard of care – a reasonably competent driver would not drive in reverse when they need to go forwards.

Dustin’s situation on the other hand can be likened to that in Mansfield v Weetabix[1998] EWCA Civ 1352. He is unaware of his medical condition, and the medical condition can be described as the cause of the accident. As such, the applicable standard will be that of a reasonably competent driver suffering from undiagnosed narcolepsy. Much like in Mansfield v Weetabix, this means that Dustin is unlikely to be held liable for the accident – he had no control over his medical condition and was not aware of it. Dustin will only be held liable if the court finds that someone with his condition could still have reasonably acted to prevent the accident from taking place.