By Law Teacher

4.3.1 Vicarious Liability – Introduction

Welcome to the third lesson of the fourth topic in this module guide – Vicarious Liability! In certain circumstances it is justified to make an employer liable for the negligent acts of another. The basis for this is that the employer may have control over the employee’s actions, be more capable of rectifying the losses and in any case should bear the risks, as much as the benefits, of his enterprise.

At the end of this section, you should be comfortable identifying the types of relationship and scenario where vicarious liability exists. You should have an appreciation for how this relates to the justification for the imposition of secondary liability in this manner.

The section begins by defining vicarious liability and then moves on to discussion the first of three primary requirements; A relationship of control. Once this has been explored, the section discusses the second requirement of establishing a tortious act. Finally, there is discussion of the requirement that the tortious act must be done in the course of employment. The section concludes with a consideration of employers’ indemnity.

Goals for this section:

- To understand in which types of scenario vicarious liability should and does arise.

Objectives for this section:

- To be able to define vicarious liability and the requisite elements to establish it.

- To understand how the courts have interpreted and defined a relationship of control.

- To appreciate why the law requires these elements to be established before vicarious liability will be established.

4.3.2 Vicarious Liability Lecture

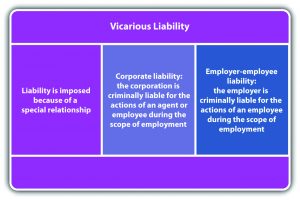

Vicarious liability deals with situations in which an individual has committed a tortious act whilst acting on behalf of another. The primary situation in which the concept will arise is one in which someone is acting on behalf of an employer. An explanation for this phenomenon can be seen in Dubai Aluminium Co Ltd v Salaam [2002] 3 WLR 1913 per Lord Nicholls:

“The underlying legal policy is based on the recognition that carrying on a business enterprise necessarily involves risk to others. It involves the risk that others will be harmed by wrongful acts committed by the agents through whom the business is carried on. When those risks ripen into loss, it is just that the business should be responsible for compensating the person who has been wronged.”

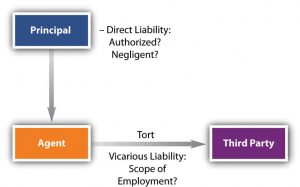

Vicarious liability is a way in which any of the other torts can be attributed to a particular defendant, even if that defendant was not directly involved in the tort.

Establishing vicarious liability requires three primary criteria to be met. There must be a relationship of control, a tortious act, and that act must be in the course of employment.

Relationships of Control

The courts will first look for a sufficiently close relationship between tortfeasor and third party before it allows vicarious liability to be imparted. Since most people will at some point have an employer, this tends to be the most frequently encountered situation. However, certain other relationships give rise to vicarious liability.

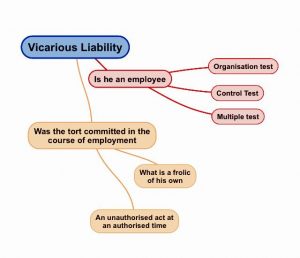

Since the most commonly encountered relationship is employer-employee, it is important to know the features which define such a relationship. The law has developed a number of tests to distinguish between employees and contractors.

The Control Test

The first is the ‘control test’. This involves asking who, exactly, is in control of the individual’s work. Employees tend to have the nature of their task dictated specifically by their employer, whilst independent contractors tend to have more personal control. The source of the control test can be found in Yewen v Noakes [1880] 6 QBD 530.

The Organisation/Integration Test

The ‘organisation’ or ‘integration test’ distinguishes between people who sign ‘contracts of service’ and those who ‘contract to provide services’. Employees tend to do work which is integral to the business’s operations, whilst independent contractors tend to do work which is ancillary to the main functions of the business. This principle can be seen at play in Stevenson, Jordan & Harrison Ltd v MacDonald & Evans [1952] 1 TLR 101.

The Economic Reality Test

The ‘economic reality test’ is sometimes referred to as the ‘multiple test’ or the ‘pragmatic test’. It involves examining the characteristics of the subject’s work arrangements against a checklist of signs of conventional employment. The test appears in Ready Mixed Concrete Ltd v Minister of Pensions [1968] 2 QB 497where it was said that there are three criteria which must be met before employee status can be granted:

- Firstly, the individual must provide work or skill for the employer in return for payment or other remuneration.

- Secondly, the individual must have agreed (either expressly or impliedly) that they will work under the control of the employer.

- Thirdly, the other circumstances of the individual’s working arrangements must be consistent with those of an employee.Particular characteristics to look out for include:

- Working hours being fixed;

- Payment being regular;

- Tax being taken from the employer;

- Equipment provided by their employer;

- Limited independence.

It should be noted that the economic reality test is by no means exhaustive, Market Investigations Ltd v Minister of Social Security [1969] 2 QB 173.

Establishing a Tortious Act

Once a sufficiently close relationship has been established, it must be shown that the individual has committed a tortious act. This is because no secondary liability can be imposed on a third party before someone acting on their behalf has attracted primary liability.

This means that whether vicarious liability is possible depends on whether liability exists for the relevant tort. One technicality should be noted. If the employee (etc.) enjoys immunity from lawsuits by merit of their personal status, their employer will not receive the same protection, Broom v Morgan [1953] 1 QB 597.

Tortious Acts Must be in the Course of Employment

An employer is not responsible for all of the acts one of their employees carries out. Instead, for vicarious liability to be possible, the tortious act must occur in the course of employment. If the relevant relationship is not employer-employee, then the same principle applies but in a modified form. There are several categories of employment scenarios which can arise with regard to this element of vicarious liability.

Authorised Acts

It will sometimes be simple to see when a tortious act is done in the course of employment – most notably when an employee is directly following their employer’s express orders and in doing so, commits a tort.

However, express authorisation is not an ever-present feature of many employment situations (particularly where an employer knows they are doing wrong – they are unlikely to put such orders in writing.) The key thing to ascertain is then whether an employee has been given implied authority to act due to the scope of their employment.

Implied authority can be seen in Poland v Parr & Sons [1927] 1 KB 236.

Authorised Acts in an Unauthorised Manner

Situations will often arise in which an employee is undertaking an authorised act, but does so in an unauthorised manner. An example of this can be seen in Century Insurance v NI Road Transport Board [1942] AC 509.

A distinction can be made between situations in which an employee acts within their employment responsibilities (as in Century Insurance), and when they act outside of them (albeit with the intention of aiding their employer.) An example of this distinction can be found in Beard v London Omnibus Co [1900] 2 QB 530. The courts rejected vicarious liability – the conductor was acting outside of the course of his employment here.

Explicitly Prohibited Acts

As might be expected, the courts will usually deny vicarious liability when an employer has expressly prohibited an employee from taking a particular action. However, it is important to note that whilst a prohibition against taking a particular action will be sufficient to break the link between the employee’s conduct and the employer, the same cannot be said when an employer has merely prohibited an employee from taking an authorised action in an unauthorised way. This distinction is often referred to as the difference between scope of action and manner of action. Scope of action can be seen in Iqbal v London Transport Executive [1973] EWCA Civ 3 (another, but different bus conductor case!) A bus conductor was prohibited from driving – it was explicitly outside of the scope of his duties. Nonetheless, he decided to move a bus that was blocking a depot but crashed, injuring another employee. The court rejected vicarious liability on the basis that the conductor’s conduct was beyond his duties.

In contrast, prohibited manner of conduct can be seen in London County Council v Cattermoles (Garages) Ltd [1953] 1 WLR 997. The employee worked for a garage, which had petrol pumps outside. Part of the employee’s duty was to assist in the movement of vehicles around the garage, and this included either pushing them by hand, or guiding their drivers as they undertook tricky manoeuvres. The employee jumped into a van in order to move it, and drove out into busy Pentonville Road in order to come back around into the garage. It was at this point that he hit the claimant’s vehicle. The defendant employer argued that they should not be held vicariously liable, since they had prohibited such behaviour. The courts rejected this argument – whilst they had prohibited the manner of his conduct, he was still engaged in his duty – moving vehicles around to ensure the smooth running of the garage.

Unlawful Activity

Another category of cases exists in which employees take criminal actions during their employment. Whilst these will often fall outside of the scope of vicarious liability, this is not a given. The test is whether a sufficiently close connection exists between the criminal conduct and the employee’s usual conduct. This can be seen in the unfortunate case of Lister et al. v Hesley Hall Ltd [2002] 1 AC 215.

This principle has been extended relatively far by the courts, as in Mohamud v WM Morrison Supermarkets plc [2016] UKSC 11. This claim was successful. Although the employee’s conduct was clearly beyond his employment, it was nonetheless held to have occurred during the course of it.

Distinguishing Between Employment and Personal Conduct

It will often be the case that the lines between employment conduct and personal conduct are blurred. Further complications can occur when personal conduct occurs within working hours and in the workplace (so between 9-5 and in the employee’s office, for example.) The law, thus, makes a distinction between an employee’s conduct which is in the course of employment and conduct which can be considered ‘a frolic of his or her own’. This distinction can be traced back to Joel v Morison [1834] 172 ER 1338.

The distinction between employment conduct and a personal frolic becomes a little clearer when Storey v Ashton [1869] LR 4 QB 476 is examined. The defendant employer, a wine merchant, sent his carriage driver to deliver some wine. After he had finished the deliveries, the driver went to visit his brother-in-law. During this journey he knocked down the claimant and injured him. The courts rejected the claim against the driver’s employer – it was held that the driver was engaged in a new and absolutely unauthorised journey.

Thus, the distinction between Joel and Storey can be seen – in the former case, the driver was doing his job, and took a diversion in which he caused an accident. In the latter, the driver had finished his work when he took the ill-fated diversion.

Employers’ Indemnity

Since vicarious liability depends on the existence of primary liability, both employer and employee are joint tortfeasors. This means that it is often the case that employers can recover from their employee for their misdeed. There are two primary ways in which this can happen. Firstly, the Civil Liability (Contribution) Act 1978 provides a given defendant who has paid damage with the ability to recover a contribution to those damages from any other party who has contributed to the claimant’s harm. The split will be decided by the courts on the basis of what is ‘just and equitable’ as per s.2(1) of the Act.

Under the common law, it is possible for a defendant to recover an indemnity (a full recovery) for their loss from their employee if the employee has acted in breach of contract. This was the case in Lister v Romford Ice & Cold Storage Co Ltd [1957] AC 555. The defendant was held vicariously liable when one of their employees negligently backed over another employee in a lorry. The defendant’s insurance company then brought a case on behalf of the defendant against the employee. They were successful – the employee had not been acting with reasonable care and skill, and thus had breached an implied term of their contract.

However, the contract law means of acquiring an indemnity is only available to defendants when they have acted beyond reproach. If they are even partially to blame for their employee’s conduct, they will be restricted to the statutory course of action, as per Jones v Manchester Corporation [1952] 2 QB 852. The defendant hospital board sought to reclaim the damages it had paid out for a junior doctor’s mistake. However, the board was held to be partially at fault – it had failed to provide him with proper supervision. The claim for an indemnity for breach of contract, therefore, failed.

4.3.3 Vicarious Liability Lecture – Hands on Examples

Question:

Serenity Corp are a food wholesalers operating out of a large warehouse. Food is purchased there in bulk, either in person or via order.

One day, a number of incidents occur in the warehouse.

Employees Malcom and Zoe meet with a customer, who wishes to buy a large quantity of rice. The desired product is on a high shelf, some two stories up on the warehouse’s industrial shelving. Ordinarily, they would use a forklift system to retrieve the pallet the rice is on. Today, however, the lift is already in use. The wholesalers is busy, and so Malcom and Zoe decide to retrieve the rice on their own. They have attempted this once before, and were caught by their employer, who forbade them from retrieving products in this manner.

Zoe climbs up the shelving, and after ensuring Malcom is ready, she shifts the bag of rice off the pallet. Unfortunately, another customer is walking by when the bag falls off of the shelves. It misses Malcom (who was intending to catch it) and it hits the customer, who is knocked to the floor and suffers a broken arm.

Rice is spilled over the floor, and so Malcom and Zoe call over Kaylee – a cleaner. Kaylee is employed by Serenity Corp on a casual basis, three days each week. They ask that she wears their uniform, and that she is polite to customers as she works. Kaylee works on an independent basis – she operates under her own name, and files a tax return each year declaring her income. Kaylee jumps onto the warehouse’s sweeper machine – an industrial unit used to make cleaning up large spills easier. On her way to the spill she accidentally runs over the foot of a customer. The customer’s foot is broken, and he swears loudly at Kaylee.

Jayne, a cashier, hears the customer yelling at Kaylee. He is rather protective of her and rushes over and berates the customer for his poor attitude. The customer refuses to back down, and so Jayne hits him, breaking his nose.

Meanwhile, Hoban, a delivery driver, is out on a job delivering beef to a customer. He is still on his way out when he decides to stop for lunch at a drive-through restaurant. Whilst stopped at the order window, he accidentally puts his delivery van in reverse, and hits the driver behind him.

Serenity Corp is now facing four claims – one for the broken arm, one for the broken foot, another one for the broken nose, and a fourth for the vehicle damage.

Advise Serenity Corp on whether it will be held vicariously liable for these claims.

Answer:

The first claim deals with vicarious liability for authorised acts undertaken in an unauthorised manner. As per Century Insurance v NI Road Transport Board[1942] AC 509, an employer can be held liable for acts which take place in the course of employment, even if they are undertaken in a careless manner. The express prohibition by Serenity Corp will not provide a defence – the prohibition only refers to the manner of Malcom and Zoe’s conduct, rather than the scope. Since the pair were acting within the bounds of their employment (i.e. retrieving products for customers), the courts are likely to impart vicarious liability, as in London County Council v Cattermoles (Garages) Ltd [1953] 1 WLR 997.

The second claim, for the cleaning machine accident, will depend highly upon whether Kaylee is considered an employee of Serenity Corp or not. The control test, as per Yewen v Noakes [1880] 6 QBD 530, can be interpreted either way – whilst it is unlikely that her employer provides direct instructions on how to clean up, we know that they have provided an industrial cleaning unit, and so have at least some bearing on her way of working. The organisation test of Stevenson, Jordan & Harrison Ltd v MacDonald & Evans [1952] 1 TLR 101 suggest she is not an employee – whilst her conduct is certainly of use to Serenity Corp, her work can be categorised as accessorial to the primary business of the company. Applying the economic reality test, of Ready Mixed Concrete Ltd v Minister of Pensions [1968] 2 QB 497, renders a similar result. Kaylee receives remuneration and her employer exercises a certain level of control over her conduct. However, it appears she is expressly regarded as an independent contract by her employer, since she takes the step of paying her own taxes and appears to have the ability to freely work for others as she wishes. Whilst she wears the uniform of Serenity Corp, so did the employees in Ready Mixed Concrete, and that formed no barrier to independent contractor status. Whilst the company have provided Kaylee with equipment, it would arguably be impractical for her to personally provide such equipment, even as an independent contractor. Thus, since Kaylee is likely an independent contractor, the liability for the customer’s injury is her own.

Jayne’s action mirror those of the employee in Mohamud v WM Morrison Supermarkets plc [2016] UKSC 11 – there is an attack on a customer whilst on the job. This suggests that vicarious liability will be imparted to Serenity Corp. However, it might be argued that Jayne’s actions can be distinguished, since the altercation was not one which started with Jayne serving a customer, but instead one that started when Jayne involved himself in a dispute that he was separate from.

Finally, there is the damage Hoban causes whilst on a delivery job. Whilst it is certainly true that Hoban is not directly engaged in his duties when the accident occurs, it can still be regarded as occurring during the course of employment. As in Joel v Morison [1834] 172 ER 1338 the crash occurs midway through a delivery job. His conduct is not so wildly deviant that it might be considered personal frolic, as in Storey v Ashton [1869] LR 4 QB 476. Indeed, it is perfectly usual conduct for a delivery driver to take reasonable breaks for refreshment, and it would be undesirable for the law to disincentivise drivers from ensuring they take breaks where necessary.