By Law Teacher

10.1.1 The Judiciary – Introduction

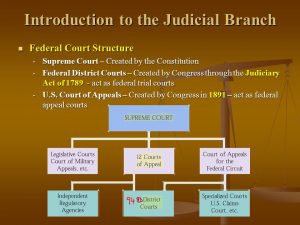

Welcome to the tenth topic in this module guide – the Judiciary! The judiciary is the system of courts that interprets and applies the law. The role of the court system is to decide cases, including the determination of the relevant facts, then the determination of the relevant law and the application of the relevant facts to the relevant law. In England and Wales there exists a range of courts, which operate in a hierarchical system and undertake an array of functions.

At the lowermost level of the hierarchy is the Magistrates’ Court, the County Court and the First Tier Tribunal. The Magistrates’ Court adjudicates the less serious criminal offences, whereas the County Court and the First Tier Tribunal adjudicate civil matters. The Crown Court is one level above the Magistrates’ Court and also hears criminal cases; these are of a more serious nature than the cases heard in the Magistrates’ Court.

At the subsequent level of the hierarchy the High Court and the Upper Tribunal exists. The Court of Appeal (which is divided into a civil division and a criminal division) is one level above the High Court and the Upper Tribunal.

At the uppermost level of the hierarchy is the Supreme Court.

Below are some goals and objectives for you to refer to after learning this section.

Goals for this section:

- To understand the hierarchy of the courts.

- To identify the specialisms the court structure is divided into.

- To understand the difference between the civil division, the criminal division and the administrative division.

Objectives for this section:

- To be able to analyse the role of the judiciary.

- To be able to understand the separation of powers doctrine.

- To be able to comprehend the courts’ role in the United Kingdom’s constitution.

- To be able to understand how judges are appointed.

10.1.2 The Judiciary Lecture

A. Introduction

This hierarchy of courts is important in ensuring the administration of justice functions effectively within the court system and in particular in relation to public law. It acts as an important limitation on the abuse of the powers of the Executive and Legislative branches of government.

B. The Structure of the Judicial System

United Kingdom Supreme Court

Court of Appeal

(Criminal Division)

Court of Appeal

(Civil Division)

Court of Appeal

(Civil Division)

Upper Tribunal

High Court

High Court

High Court

Crown Court

First Tier Tribunal

County

Court

Magistrates’ Court

Figure 10.1 The Judicial System in England and Wales

Criminal and Civil Divisions

The court structure is divided into specialisms. There are three divisions in this respect: the criminal, the civil and the administrative division.

Case in Focus R (Alconbury Developments Ltd) v Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions [2001] UKHL23; [2003] 2 AC 295, [26]

C. The Role of the Judiciary

The role of the court system is to decide cases, including a determination of the relevant facts, then the determination of the relevant law and the application of the relevant facts to the relevant law. The courts must ascertain what the relevant facts are; this may require a court to resolve a dispute about the facts.

Secondly, the court must determine the relevant legal rules to apply in the particular case. In certain instances, the court may even be required to clarify, develop or supplement existing legal principles in order to apply the law to new factual situations.

Finally, courts must apply the law to the facts; it must determine that the facts satisfy the relevant legal requirements of the criminal offence or civil liability.

There are bodies other than courts who also resolve disputes between parties; these include matters of private law that might be resolved through arbitration. Alternative dispute resolution (ADR) refers to a method of resolving disputes which do not resort to involving the court system. The existence of such mechanisms for dispute resolution is important for three principal reasons.

- Courts operate as a longstop.

- Courts can exercise the coercive powers of the state.

- The courts are also a necessary element of the separation of powers doctrine.

The courts’ role in the UK Constitution

Courts act as the adjudicators in cases that involve public law. They are frequently asked to determine a case where a public body has infringed the rights of a private individual and are required to rule on the legality of a decision made by a public body. In judicial review cases, courts are required to consider whether a public body has adhered to the special legal standards to which branches of government are required to adhere. These standards include the principles of good decision making, the relevant aspects of the rule of law and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) principles which are protected by the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA).

Public bodies also possess a protection function. A public body might make a decision for the common good that is not in the interests of certain private individuals. Hence, it is clear that there are often conflicts, which arise between private individuals and the state in the form of public bodies due to their decision-making powers and the ways in which these impact upon the rights and interests of individuals or private companies. Particularly since the introduction of the HRA, the courts have had a growing role in acting as watchdog to protect the constitution, particularly in the light of the peculiarly powerful position of the Executive branch within the UK.

Case in Focus R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex p Fire Brigades Union [1995] 2 AC 513

Unlike in other countries, the courts are constrained by the principle of parliamentary sovereignty and are unable to strike out primary legislation as unconstitutional. The courts’ powers to uphold constitutional principles, such as the rule of law or the separation of powers, are limited by contrary provisions within an Act of Parliament.

Functions other than Dispute Resolution

The resolution of disputes is necessarily a retrospective function; however, courts are capable of also acting in a more forward-looking manner. Under the doctrine of precedent, higher courts including the Court of Appeal and UK Supreme Court can make decisions that clarify specific points of law and bind the lower courts in a prospective fashion.

Case in Focus Regina v R (Rape: Marital Exemption) The Times, 24 October 1991; (1992) Cr.App.R. 216.

Courts have also provided ‘advisory opinions’ in situations that do not disclose any live disputes; but present an answer to a hypothetical question of law responding in a way that would answer the question as to whether such a given set of facts were to arise, what in these circumstances would be lawful.

Case in Focus Airdale NHS Trust v Bland [1993] AC 789

The emphasis of such advisory opinions is upon public functions, and the aim is to make certain that public bodies act in the public interest. As such, the higher courts are able to provide advisory opinions in order to make authoritative rulings on the current state of the law so that public administration is carried out in a lawful manner in the first place.

Can Judges Make the Law? The Separation of Powers Doctrine

In Duport Steels Ltd v Sirs [1980], Lord Diplock stated “Parliament makes the laws, the judiciary interpret them”. Parliament is not the only body that makes laws, since administrative bodies pass a wide range of secondary legislation. The courts do; however, also contribute to the law-making enterprise in two ways:

- Courts interpret legislation.

- Legislation must also be interpreted in line with EU law and Convention rights within the ECHR.

- Judges also more obviously create law when they create new rules of common law.

Are these functions of judicial law making compatible with the separation of powers doctrine which states that the legislative and hence law-making function rests with Parliament. As was discussed in previous chapters, the UK does not have a pure separation of powers and the courts’ role in statutory interpretation helps guard against the abuse of power. It helps to prevent any particular branch of government from holding excess power (in this case theoretically Parliament, but in practise it is often a safety valve on the power exercised by the Executive).

Furthermore, the courts’ law-making powers are usually quite limited. Similarly in creating common law, courts are restricted by past precedent. It is always open to Parliament to legislate when courts make decisions that the Executive does not feel is in line with Government policy. E.g. R v Davis [2008] UKHL 36, [2008] 1 AC 1128. Shortly after this decision, Parliament enacted the Criminal Evidence (Witness Anonymity) Act 2008.

As unelected judges the courts are not subject to the democratic selection by the public, and hence the separation of powers doctrine requires that there are significant limits on the courts’ law making powers. This has been made clear by the courts themselves, when they have refused to rule on a particular question stating that a particular matter requires an Act of Parliament to make changes to the law.

Case in Focus C (A Minor) v Director of Public Prosecutions [1995] Cr App R 136, [1995] UKHL 15, [1996] AC 1

This legal change came in the form of section 34 Crime and Disorder Act 1998. The courts deferred to the law-making power of Parliament recognising that to have abolished such a rule within common law would have been to act outside of their own law-making capacity.

D. Judicial Appointments

i. The Judiciary

The Executive is responsible for the judicial appointments in the UK. The Queen, with the advice of the Prime Minister (PM), makes appointments in the UK Supreme Court. The Lord Chief Justice, the Master of the Rolls and the President of the Family Division are appointed, along with other senior roles, on the advice of the PM and the Lord Chancellor. The Queen, on the advice of the Lord Chancellor, appoints High Court judges; this is the same for circuit judges and recorders.

There are of course minimum requirements for judges to be qualified to take such a role. Since the Courts and Legal Service Act 1990, solicitors with rights of audience in the High Court and barristers’ of ten years call or more as well as circuit judges of two years’ standing can be appointed as High Court judges. Since the 1990 Act, candidates for appointment as Lord Justice of Appeal in the Court of Appeal must have at least 10 years standing as a barrister, or a solicitor with rights of audience in the High Court. Those who have already been a High Court judge may also be appointed.

In practice appointments to posts in the superior courts is frequently made of those individuals who have much more than the statutory minimum qualifications. It is exceptional that a person is appointed to a senior judicial position than through promotion through the other judicial positions.

ii. Judicial Appointments Commission

The widespread criticism of the lack of transparency in the judicial appointments process was the impetus for the passage of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005. The Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC) was established by an Order in Council in April 2006 to review judicial appointments. Its formation includes a lay chairperson as well as a number of other Commissioners.

In the event of a vacancy needing to be filled within a number of senior posts, the Lord Chancellor may request the Commission to establish a selection panel; two must be judges and two are not to be legally qualified. Two of the members of the panel must also be members of the Commission. In all judicial appointments, the end of the process is when a recommendation is made to the Lord Chancellor who can ask the panel to reconsider or reject the appointment altogether.

The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 (as amended) provides that the UK Supreme Court is to consist of twelve full time judges. Serving justices of the Supreme Court are prohibited from taking an active part in the legislature. The Supreme Court was established on 1 October 2009; appointments do not have to have prior judicial experience.

Vacancies to the Supreme Court are filled through the appointment of an ad hoc Supreme Court Selection Commission, although the President of the Court is appointed differently. The Supreme Court (Judicial Appointments) Regulations 2013 includes further rules regarding the appointment and selection of members of the Supreme Court.

Judicial diversity has become an important question in recent years. Judicial statistics for 1 April 2015 state that only 12% of all judges under 50 declare their ethnicity as black or minority ethnic. There are increasing numbers of female judges, with the percentage of female High Court and Circuit Judges at 19.8% and 22.8% respectively. Despite developments over the past two decades there has been little discernible change in the gender and ethnic composition of the judiciary.

E. Judicial Independence

The right to have legal proceedings that are unbiased is a fundamental human right and is incorporated within Article 6 ECHR. Certain steps have been taken in recent years to ensure that there is a sufficient separation between the judiciary as an institution and the other branches of government.

- The first of these steps was the establishment of the UK Supreme Court by the Constitutional Reform Act 2005.

- The Lord Chief Justice took over the role of the Lord Chancellor who is now solely a Government Minister and is in charge of the Ministry of Justice.

An independent judiciary is thus an essential element of the separation of powers doctrine. Although changes in recent years may have been aimed at changes in public perception rather than actual changes, public perception that justice is fair is also an important element of the need for independence.

10.1.3 The Judiciary Lecture – Hands on Examples

The following essay style questions provide example questions that can test your knowledge and understanding of the topics covered in the chapter on the Judiciary and the courts. Suggested answers can be found at the end of this section. Make some notes about your immediate thoughts and if necessary, you can go back and review the relevant chapter of the revision guide. Working through exam questions helps you to apply the law in practice rather than just having a general understanding of the legal principles. This should help you be prepared for particular questions, which may be presented in the exam.

Q1 Do judges make the law?

Q2. Does the current system of judicial appointment lead to a suitably transparent process and sufficient diversity within the serving judiciary?

A1 The separation of powers doctrine states that it is for the legislature (i.e. Parliament) to create law, they are the political representatives of the people and have been elected into their positions which means they should represent the public interests in the passage of legislation. However, there are certain ways in which is can be argued that judges do create laws.

– It was stated by Lord Diplock in Duport Steels Ltd v Sirs [1980] 1 WLR 142, 157, that “Parliament makes laws, the judiciary interpret them”.

– Judges interpret existing legislation, where a term in an Act of Parliament is unclear it is the judges’ role to consider what the various interpretation of a term in a Statute is and choose between them.

-Judges are also required to uphold the rights within the Human Rights Act 1998 and make sure that statutes comply with EU law. The HRA creates provision for judges to read into a statutory provision its compliance with Convention rights, this might have a significant impact upon the legal application of a specific provision of legislation.

-Judges also create new rules of common law. These are intended to be incremental changes, but over many years and decades of areas such as criminal law where many offences are still bound by common law, judges have created large areas of legal regulation over time.

For example, in Regina v R (Rape: Marital Exemption) The Times, 24 October 1991; (1992) Cr.App.R. 216 the House of Lords effectively created a new criminal offence of the act of rape within marriage. It had previously not been an offence of a man to rape his wife, as it was argued that through the marriage contract women gave themselves to their husband and was unable to withdraw consent. The House of Lords acknowledged the changes in society that made it no longer acceptable to suggest that rape in marriage was not possible.

Contrast this case with C(A Minor) v Director of Public Prosecutions [1995] Cr App R 136, [1995] UKHL 15, [1996] AC 1, where the court acknowledge that is was not their role to abolish the doli incapax rule and that it was for Parliament to legislate on the matter, which they did in the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, section 34.

A2 Judicial appointments in the UK are made by the Queen with advice of the PM, and the Lord Chancellor. The Courts and Legal Services Act 1990 provided that solicitors could obtain rights of audience in the High Court and hence both solicitors and barristers (of 10 years call) could be appointed as High Court judges. It was also possible at this stage for circuit judges also to be appointed to the High Court.

-Widespread criticism of the lack of transparency and diversity within the judicial appointments process led to the passage of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005. A year later the Judicial Appointments Commission was created through an Order in Council in 2006.

-The Lord Chancellor requests that the JAC form a selection panel in the event of a vacancy for a senior judicial appointment. There is a mandatory composition for this selection panel including two members of the JAC, two judges and two non-lawyers. The panel makes a recommendation to the Lord Chief Justice who can reject or accept the recommendation.

-The establishment of the UK Supreme Court by the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 meant that law (rather than convention) now prohibits serving justices from taking an active part in the legislature. Judges will not obtain peerage by virtue of their membership on the Supreme Court.

– To fill a vacancy in the Supreme Court, an ad hoc Supreme Court Selection Commission is established, which must include a member of the Supreme Court, three members of the JAC and a non-lawyer.

– Despite these changes, little impact has been had upon the diversity of gender and race within the judiciary, particularly in the senior roles. Judicial Diversity Statistics 2015 (p.3) reveal that 12% of judges under 50 declare themselves as black or minority ethnic, which is in line with the general population in which 86% of the population describe themselves as white (Office of National Statistics, 2012)

-However, the gender diversity is less encouraging with the percentage of female High Court and Circuit Judges at 19.8% and 22.8% respectively.

– At the most senior levels, there are no Lord Justices of Appeal that describe themselves as coming from a BME background. There are 8 Lord Justices of Appeal who are female, which constitutes just over 20% of the total number (Judicial Diversity Statistics 2015, p.4)

– There are no Lord Justices of Appeal who have come from the professional background as a Solicitor-Advocate (Judicial Diversity Statistics 2015, p.5)

-Although throughout the judiciary there have been changes in the number of women, of ethnic minorities and solicitor advocates taking on roles, at the highest levels all three of these groups are still significantly underrepresented. Since it is the Lord Justices of Appeal who make the most important legal policy decisions, to be representative of the population as a whole, this situation needs to change.