By Law Teacher

11.1.1 What is Judicial Review – Introduction

Welcome to the eleventh topic in this module guide – What is Judicial Review! During the late twentieth century, the government’s role expanded; they begun to deal with areas that they previously had no interaction with. After the welfare state had been established there were new roles within education, immigration, housing and health. There was, therefore, a greater possibility for the government to come into conflicts with individuals. As a result of this, the ideologies of judicial review were established during the 1960s in the House of Lords with Lord Reid at the forefront.

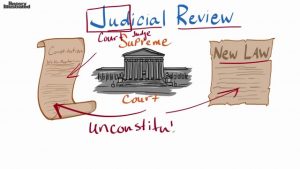

Part 54.1 of the Civil Procedure Rules defines judicial review. Judicial review is a sort of court proceeding whereby a judge reviews the lawfulness of a decision or action, or a failure to act, by a public body. One of the foremost objectives of judicial review is to hold the government accountable; this means the controlling, checking or regulating of the government. Judicial review is begun in the Administrative court by organisations or individuals affected by the exercise of state power.

Below are some goals and objectives for you to refer to after learning this section.

Goals for this section:

- To understand what judicial review is.

- To be able to identify the grounds for judicial review.

- To understand the link between judicial review and the constitution.

Objectives for this section:

- To be able to distinguish between judicial review and appeal proceedings.

- To be able to analyse the effectiveness of judicial review.

- To be able to appreciate how the Human Rights Act 1998 and judicial review intertwine.

11.1.2 Judicial Review lecture

A. Introduction

One of the main objectives of judicial review is to hold the government to account. Accountability means the checking, controlling or regulating in the case of judicial review, of government so that it is held to account in relation to the principles of administrative law.

The role of the courts in acting as a check on the government is different to that of Parliament. Judges are non-political; they are unelected and cannot call the executive to account without an individual or organisation whose rights have been violated bringing a matter to them.

Part 54.1 of the Civil Procedure Rules defined judicial review.

Judicial Review is initiated in the Administrative court by individuals or organisations that are affected by the exercise of state power; the courts enforce the rule of law by ensuring the public bodies do not act in excess of their legitimate powers. The courts ensure that public bodies are acting rationally, reasonably and proportionally. The courts will also require that executive power is exercised in conformity with the rights and freedoms that are provided for within the European Convention on Human Rights [ECHR].

B. The History of Judicial Review

A series of coherent principles of judicial review were established during the 1960s, led by Lord Reid in the House of Lords. The law of procedural fairness was reformed first, then substantive review and aspects of the relationship between the law and the Crown were reformulated and strengthened. Finally, jurisdictional review was revisited and reformulated.

The most recent version of the Civil Procedure Rules 1998 was introduced in April 1999.

C. Grounds for Judicial Review

Case in FocusCouncil of Civil Service Unions v Minister for the Civil Service [1985] AC 374

The grounds for judicial review will be considered with in more detail in section 11.2.

D. Judicial Review and the Constitution

The principle of parliamentary supremacy provides the foundation for judicial review. The courts cannot strike down legislation for being unconstitutional in the UK, but they do ensure that those exercising public functions are acting within the limits of their powers. Some authors have suggested that the constitutional basis for judicial review is the ultra vires principle.

A consequence of the separation of powers, there are some decisions of the courts that the courts are reluctant to review. Traditionally, issues of national security, defence, and foreign affairs have been treated with particular caution by the courts. E.g. Council of CivilService Unions v Minister for the Civil Service[1985] AC 374.

Case in FocusA v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2004] UKHL 56 (Belmarsh detainees case)

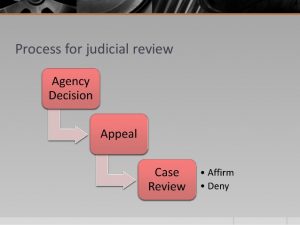

E. Distinguishing between Judicial Review and Appeal

The distinction between judicial review and appeal proceedings relates to the power of the court; in appeal proceedings the court might substitute its decision for the decision of the court at first instance. In judicial review proceedings the courts basic power is to quash the challenged decision and to find it invalid; for the merits of the case to be determined the case must return to the original decision-making authority.

The second main distinction relates to the subject matter of the court’s jurisdiction. The appeal court has to decide whether a decision was right or wrong based on the considerations of law. The judicial review court has the ability to decide if the question was legal, based upon the appropriate powers that the public body have been endowed with.

Case in FocusR v Cambridge Health Authority, ex p B (No.1) [1995] 1 WLR 898

F. The Human Rights Act 1998 and Judicial Review

Section 3 of the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA) requires that courts in so far as it is possible to do so, read and give effect to legislation in a way that is compatible with rights and freedoms under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Courts must also take account of decisions of the European Court on Human Rights (ECtHR) in interpreting the ECHR under section 2 HRA. Higher courts are able to grant a declaration of incompatibility of a statutory provision with an ECHR right under Article 4 HRA. A fast track procedure is available under section 10 HRA.

Case in FocusR (on the application of F and Thomspon) v Home Department [2010] UKSC 17

i. Grounds for judicial review under the HRA

Under the HRA, it is possible for a claimant to argue that a breach of a Convention right was a ground for judicial review. Section 6 of the HRA provides that it is unlawful for a public authority to act in a way that is incompatible with the HRA. Section 7 HRA requires that a claimant be a victim of the unlawful act. Judicial review claims under the HRA must be brought within 3 months under section 7(5)(a)(b) HRA. The court might grant a remedy of damages under section 8 HRA.

ii Public and private authorities under the HRA

Primarily the HRA provides for claims against public authorities, but claims might also be brought against private bodies that are carrying out public functions. Since courts themselves are defined as public authorities under section 6(3) HRA they are bound by provisions of the ECHR in decision making even when making decisions which related only to private parties. In this sense, the Convention is said to have indirect horizontal effect.

Case in FocusCampbell v Mirror Group Newspapers [2004] UKHL 22

G. Judicial Review in Practice

Claimants turn to judicial review when they have exhausted other avenues of redress. If the claimant succeeds the matter will normally be remitted to the original decision maker for a new decision in the light of the court’s judgment.

i. The Judicial Review Procedure

There are a range of tribunals and courts that exercise the jurisdiction to review the legality of public actions. The claim for judicial review procedure in England and Wales is set out in part 54 of the Civil Procedure Rules. The judicial review procedure consists of two stages.

In order to obtain permission, the claimant must show that the claim was made within the time limits, the claimant has standing, and other potential avenues of redress have been exhausted.

Part 54 Civil Procedure Rules states that a claim for a judicial review means a claim to review the lawfulness of an enactment, or decisions or action in relation to the exercise of a public function. It is now possible to use judicial review proceedings to consider whether or not primary legislation in compatible with EU law, or incompatible with Convention rights under s.4 HRA.

Part 54.1 Civil Procedure Rules states that judicial review claims are concerned with the exercise of public functions, they are not limited to government bodies, but can include charities, and self-regulatory organisations that can be subject to judicial review claims through there exercise of public functions.

Case in FocusAston Cantlow and Wilmcote with Billesley Parochial Church Council v Wallbank and anor [2003] UKHL 37

The main means by which a judge determines whether a body is subject to judicial review is to look at the source of the bodies’ powers. Acts of bodies whose powers derive from statute or the prerogative will usually be reviewable. Decisions taken under contractual obligations are not considered reviewable.

Case in FocusCouncil of Civil Service Unions v Minister for the Civil Service [1985] AC 374, 409

It may be the case that the source of a body’s powers cannot be identified, in the following case the Court of Appeal held that a Panel could be reviewed due to the importance and impact of the functions it undertook.

Case in FocusR v Panel on Takeovers and Mergers, ex parte Datafin [1987] QB 815, 824-36

There is a similar wording within section 6 HRA to determine whether bodies are public authorities for the purposes of the Act. The issue of a private home that exercised a public care function has also come before the courts.

Case in FocusR v Servite Houses and Wandsworth LBC, ex parte Goldsmith (2000) 3 Community Care Law Reports 325

ii. Does the Claimant Have Standing?

Claimants must show that they have sufficient interest in a matter to bring judicial review proceedings in respect of it. Previously judges have taken a ‘closed’ approach to the persons who had sufficient interest, more latterly a more open approach has been adopted which allows claimants into court if they have an arguable case on the law.

Cases in FocusIRC v National Federation of Self employed and Small Businesses Ltd [1982] AC 617, 644, R v Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, ex parte World Development Movement Ltd [1995] 1 All ER 611

iii. Permissions stage

The permissions stage is governed by part 54(10) Civil Procedure Rules, the court decides whether it will allow the case to proceed to a judicial review hearing. This is to prevent ‘trivial complaints and busybodies’ from wasting the court’s time [Lord Diplock, IRC v National Federation of Self employed and Small Businesses Ltd]. Claims for permission are dealt with by a judge on the papers; if permission is refused the claimant might request an oral hearing. There is a possibility of appeal to the Court of Appeal under CPR 54(12).

Permission often relies upon whether there is an ‘arguable case’.

iv. The Hearing

A single judge commonly conducts the hearing, with witnesses and cross-examination being rare. The case is nearly always focused on issues of law rather than fact. Remedies are discretionary.

v. Judicial Review and Exclusivity

The process of discovery was simplified during the changes made to the judicial review process following the Law Commission’s report (1976).

Case in Focus:O’Reilly v Mackman [1983] 2 AC 237,

vi. Public Law and Private Law Proceedings

An action against a public authority might be a private law action, such as damages for negligence. If this is the case this is not a judicial review proceeding. E.g. Davy v Spelthorne Borough Council [1984] AC 262, Cocks v Thanet [1983] 2 AC 286. The decision of a body can be challenged in civil and criminal proceedings.

The enactment of the Civil Procedure Rules has led to courts taking a more flexible and pragmatic approach to whether a claimant should proceed under private law or judicial review. E.g. Clark v University of Lincolnshire and Humberside [2000] 1 WLR.

vii. Exclusion or restriction of access to judicial review

The government have sometimes inserted ouster clauses into statues providing that a body such as a tribunal should appeal or review a certain decision.

Case in FocusR v Medical Appeal Tribunal, ex p Gilmore [1957] 1 QB 574

Courts have taken a similar approach to ouster clauses, for example a clause that states ‘a decision shall not be challenged in a court of law’. These clauses seek to prohibit legal action relating to decisions of a body.

Case in Focus: Anisminic Ltd v Foreign Compensation Commission [1969] 2 AC 147

Time limited ouster clauses impose a time limit on the claimant; these are permissible. Courts have held that when the time limit has expired the clauses prevent a claim for review. E.g. R v Secretary of State for the Environment, ex p Ostler [1977] QB 122.

Parliament can also restrict the ability of judicial review by introducing alterative statutory appeal processes to a court to tribunal. E.g. R (A) Director of Establishments of the Security Service [2009] UKSC 12. The Supreme Court distinguished this case from Anisminic.

H. Conclusion: the effectiveness of Judicial Review

The effectiveness of judicial review proceedings have to be considered within the light of the courts’ limited powers under the constitution. Under judicial review it is expensive to bring a claim. Court’s powers are also limited since it is not possible to challenge primary legislation. If the executive has acted within the powers conferred to them by statute, the courts are unable to interview through the judicial review jurisdiction. Parliament has also curtailed the jurisdiction of judicial review by limiting the subject matter of the claims that can be heard through alternative statutory procedures.

11.1.3 Judicial Review lecture – Hands on Examples

The following essay style questions provide example questions that can test your knowledge and understanding of the topics covered in the chapter on Judicial Review. Suggested answers can be found at the end of this section. Make some notes about your immediate thoughts and if necessary, you can go back and review the relevant chapter of the revision guide. Working through exam questions helps you to apply the law in practice rather than just having a general understanding of the legal principles. This should help you be prepared for particular questions, which may be presented in the exam.

Q1 Shirley owns a cafe bistro, which serves food that has been prepared and cooked on the premises. The Health and Safety in Catering Authority is a non-statutory body which create regulations which relate to the standards of food safety that should be adhered to in retail outlets selling cooked food to the public. All restaurants and cafe’s need to comply with rules established by the Authority and the Authority can ultimately ban an establishment from operating that fails to adhere to these rules.

A number of customers have raised concerns about the health and safety standards, which are adhered to in Shirley’s cafe bistro. An outbreak of salmonella poisoning was traced to the establishment and the Health and Safety in Catering Authority who subsequently banned Shirley from operating a cafe bistro. Shirley and the Society of Cafe Bistro Owners wish to challenge the decision of the Health and Safety in Catering Authority on banning Shirley from operating a cafe bistro.

- Advise Shirley and the Society of Cafe Bistro Owners as to whether the Health and Safety in Catering Authority is a public body against which judicial review proceedings can be brought.

- Advice Shirley and the Society of Cafe Bistro Owners as to whether the decision of the Health and Safety in Catering Authority is a public body which is capable of being subject to judicial review.

- Advice the Society of Cafe Bistro Owners as to whether it has legal standing to bring judicial review proceedings either on its own behalf or on behalf of Shirley.

- Outline the procedure that Shirley and the Society of Cafe Bistro Owners would follow if they decide to apply for judicial review of the Health and Safety in Catering Authorities decision.

Q1

You should explain in an introductory paragraph who the parties to the claim are and that the claimant is Shirley and the Society of Cafe Bistro Owners, whereas the defendant is the Health and Safety in Catering Authority. The cause of action is that of judicial review and the claimants are asking the judge the review the legality of the decision of the Health and Safety in Catering Authority to ban Shirley from operating a cafe bistro due to her previous poor health and safety standards.

(a) Consider the criteria on public authorities as provided for within R v Panel on Takeovers and Mergers, ex parte Datafin [1987] QB 815, in which the Panel on Takeover on Mergers was also a non-statutory body with no prerogative or common law powers, but carried out important public functions and were therefore subject to judicial review proceedings.

If the Health and Safety in Catering Authority is performing a public function in upholding the standards of food safety regulations; it is an integral part of governmental-support scheme of regulation. In R v Disciplinary Committee of the Jockey Club, ex p Aga Khan [1993] 1 WLR 909, it was held that the government would need to set up a regulatory body if this body did not exist, then the body was serving a public function.

(b) If this question is a public law matter, the context of the decision would be in the course of the Health and Safety in Catering Authority acting within a public function, which it appears to be as it has power to create health and safety regulation in the catering industry. Would the claim be an abuse of process if it was brought as a private law case. In O’Reilly v Mackman [1983] 2 AC 237, the House of Lords agreed that a request for private proceedings was a abuse of procedure and should be struck out. The claims had been brought through private law proceedings to avoid the permissions requirement and the strict time limits imposed by judicial review.

Also see Clark v University of Lincolnshire and Humberside [2000] 1 WLR 1988, which highlights the greater flexibility that the courts now have in allowing judicial review proceedings since the courts now have greater powers to supervise private law cases against public authorities and the court can strike out unmeritorious claims.

(c) You should consider whether you consider the organisation has sufficient interest in bring the case for judicial review, taking account the relevant criteria established in IRC v National Federation of Self employed and Small Businesses Ltd [1982] AC 617.It was held that the federation did not have sufficient interest in the tax affairs of another set of taxpayers. Contrast this case with R v Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, ex parte World Development Movement Ltd [1995] 1 All ER 611 in which the World Development Movement was held to have interest in the matter due to the importance of the matter raised, the absence of another other challenger, the nature of the breach and the organisations prominent role in providing guidance with respect to giving aid.

(d) You should briefly outline the procedure for the judicial review process including the written or oral submissions procedure, the permissions stage and the nature of the hearing. You could also discuss any remedies that might be available to the claimants [these will be covered in section 11.2 of the guide].