By Law Teacher

3.1.1 The Rule of Law – Introduction

Welcome to the first lesson of the third topic in this module guide – The Rule of Law! How the rule of law is defined and protected is subject to a great deal of debate, although it is generally accepted that the rule is an essential part of an effective constitution. At the end of this section, you should be comfortable understanding how the rule developed, in what areas there are matters of contention, and how the rule manifests (or should manifest) itself in the UK.

This section begins by introducing the rule and outlining the history of its conception. It then goes some way to pinning down the main aspects and arguments for its specific definition, and whether the conception ought to follow a content-free or content-rich model. The section talks about whether the rule of law has been a useful concept, and how judicial interpretation of the rule has influenced its manifestation in the United Kingdom. There finally then further discussion of the intersection of the rule and the United Kingdom.

Goals for this section:

- To understand some definitions and objectives of the rule of law.

- To appreciate how the rule has manifested itself in the United Kingdom.

Objectives for this section:

- To appreciate how the rule has developed throughout history, and how 19th century academics and commentators have contributed to its definition.

- To evaluate how the rule has been used to fulfil its primary function as a constraint on government.

- To be able to analyse threats to the rule, both generally and those that manifest themselves in the United Kingdom context.

3.1.2 The Rule of Law Lecture

Introduction

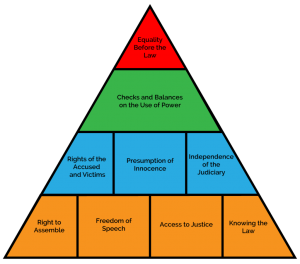

The ‘rule of law’ is widely accepted to be a critical part of an effective constitution; its principle function is to constrain government action. There is a significant disagreement initially on how to define the rule of law.

The rule of law has been referred to as a ‘wrapper’ that is placed around a bundle of constitutional principles. At one extreme, the rule of law is merely a rhetorical device or a political philosophy and its content is unimportant (the content-free view). At the other extreme, the rule of law determines the validity of law and so laws that conflict with its principles are invalid (content-rich view).

In the UK, the rule of law functions in two ways: firstly, that courts should interpret legislation in a way that gives effect to the rule of law; secondly, that the rule of law determines the validity of government action and some legislation. This is how the rule of law functions, but opinions vary on what the concept known as the rule of law means.

A. The History of the Rule of Law

In the late Roman period, the view was established that royalty was above the law and subject only to the law of God and not to other men. The path to the institutionalism of the rule of law advanced and then at times was weakened. The Magna Carta 1215 enshrined the principle that the King was not above the law. Barons demanded that King John accept the Charter after a period of domestic unrest due to the King’s focus on foreign war and his raising of taxes to finance the war with France.

In Prohibitions del Roy (1607, published 1656 (1572-1616 12 Co Rep 63) Sir Edward Cooke asserted that the King could not act as a judge using his own reason to reach decisions, but should be tried by judges who applied the law to the facts.

Petition of Rights 1628 was a petition from the Barons to the King to remind him of the principles of the rule of law established in the Magna Carta. The Petition of Rights extended the rule of law and due process to encompass some implied terms of the Magna Carta.

The right of Habeas Corpusis an essential feature of the rule of law, and is not explicitly mentioned in the Magna Carta but subject to much future legislation. It matured in legal terms in the Petition of Right. It requires a detainee to be brought before the court, so the legality of their detention can be determined and if not, the prisoner must be released.The Habeas Corpus Act 1679 specifically legislated for the fact that a detainee was entitled to be brought before a court to subject his or her detention too judicial and hence legal scrutiny.

The Bill of Rights 1689 stated that law could not be made, repealed or suspended without the will of Parliament. The Crown could not manipulate the court system, and subjects were now able to bring an action against the Monarch. The Monarch and courts could not subvert the requirements of habeas corpus. The Bill also sets out the basic and fundamental principles that determine the operation of the rule of law.

The scope of the rule of law remained vaguely defined during this period.

B. Defining the Rule of Law

Throughout the 20th century, the rule of law has become a term of widespread academic debate, court judgments and parliamentary debates. It is referred to in section 1 of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005, the preamble to the European Convention on Human Rights 1950 and the preamble to the Treaty on European Union.

Lord Bingham in ‘The Rule of Law’ (2007) 66 CLJ 67, 69 argued that

‘The core of the existing principle is … that all persons and authorities within the state, whether public or private, should be bound by and entitled to the benefit of laws publicly and prospectively promulgated and publicly administered in the courts’.

Lord Bingham subsequently defined 8 sub-rules:

- Law should be accessible, clear and predictable;

- Questions of legal right and liability should be decided by application of the law;

- The law of the land should apply equally to all, except when objective difference requires differentiation;

- Public officials should exercise their powers in good faith, and not exceed their powers;

- The law must protect fundamental rights;

- A method should be provided, at reasonable cost, to resolve civil disputes;

- Adjudicative procedures must be provided by the state should be fair;

- The rule of law requires the state to comply with its obligations in international law.

This list was adopted by the European Commission on Democracy Through Law in 2011

B. Content Free or Content Rich?

There remains a number of important questions regarding the ‘rule of law’, one important one being whether it should be content free or content rich?

Joseph Raz, ‘The Rule of Law and its Virtue’ (1977) 93 Law Quarterly Review, 195, 210-11, argues that the rule of law is a negative concept, which is merely designed to minimise the harm to freedom and dignity which the law may create in the pursuance of its goals. A content-free concept of the rule of law thus does not specify what the substantive rules should be, just that the process of the creation of law should be carried out with procedural fairness.

A content-free rule of law takes no account of social inequalities. As stated by Anotole France in Bon Mot ‘The law in its majestic equality, forbids the rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, to beg in the street, and to steal bread’. When the rule of law is applied in this content-free manner, it creates procedural fairness, while the law still functions to preserve inequalities.

Ronald Dworkin, ‘Political Judges and the Rule of Law’ in A Matter of Principle (OUP, 1985), pp1-12, supports the alternate view, challenging the content-free idea of the rule of law. Dworkin argues that the rule of law should assume that citizens have moral rights and duties with respect to one another and political rights with respect to the state as a whole. This concept of the rule of law does not distinguish between the rule of law and substantive justice; instead, it requires that as part of the rule of law that rules within the rulebook encompass and enforce moral rights.

C. Dicey and the Rule of Law

A.V. Dicey inIntroduction to the Study of Law of the Constitution (1885; 10th edn., Macmillan & Co., 1959), pp.187-95, wrote that the supremacy of the rule of law has three distinct though related conceptions.

- No individual can be punished except through the process of law and the courts.

- No one is above the law; this includes the Prime Minister who is subject to the ordinary law in the same way that other citizens are.

- The constitution is pervaded by the rule of law, since general principles of the constitution are the results of judicial decisions which determine the rights of private citizens.

Sir Ivor Jennings (1903-1965) was a Fabian socialist who criticised Dicey’s work arguing that it failed to deal with the powers of government. Dicey’s focus was only upon tort law and not public law

Despite his critics, Dicey’s three propositions are still highly influential and referred to by judges in the 21st century.

D. Is the Rule of Law a Useful Concept?

John Griffiths (1918-2010) ‘The Political Constitution’ (1979) 42 Modern Law Review, 1, 15; The Rule of Law has a correct function in ensuring that public authorities do not exceed their powers and that criminal offences are dealt with in a fair and just manner; but the concept has also been misused to preserve legal and political institutions, which are no longer relevant.

Martin Loughlin, The Rule of Law in European Jurisprudence’ Study 512/2009 (Venice Commission 2009). Since law is acknowledged to be a human creation, it cannot be placed above the human intention. Laws themselves do not rule, since ruling requires action and laws cannot act. The rule’s main strength is as an aspiration, but it must be recognised that its direction remains an essentially political task.

Each country has its own institutions, which protect the rule of law; in the UK, this is done so by the three branches of government: The Judiciary, Parliament and the Government.

E. Judicial interpretation of the rule of law

The courts have interpreted the rule of law through a selection of cases that have examined the legality, the irrationality or the procedural impropriety of the actions of the executive or public bodies, or whether their actions conform to the Human Rights Act 1998. The main principles of the rule of law, along with judicial interpretation are considered here.

i. No one must be punished by the state except for a breach of the law:

- Punishment without trial has been brought back into focus due to anti-terrorism legislation, including Section 1 of the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 (now repealed).

- In A and others v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2004] UKHL 56, it was held indefinite detention without trial was always illegal; its justification had to be utterly exceptional.

ii Government under law; equality before the law:

- In Entick v Carrington (1765) 19 St Tr 1029, Lord Camden CJ held: ‘By the laws of England, every invasion of private property, be it ever so minute, is a trespass.’

- In M v Home Office and another [1994] 1 AC 337 HL, the principle that the executive is subject to full judicial oversight was upheld.

- In R v Mullen [2000] QB 520, it was confirmed that whatever the crime an appellant is accused of, it does not justify the state acting outside the law.

iii Individuals’ rights are protected through the ordinary law and the ordinary court system:

- The process of judicial review allows an individual to challenge a decision of the executive through the courts.

- In R (on the application of G) v IAT and another; R (on the application of M) v IAT and another [2005] 2 All ER 165, the CA found that an alternative statutory regime, although not as extensive as judicial review, did provide access to judicial scrutiny and oversight of judicial action. It was not found to be a breach of Article 6 (the right to a fair trial) of the ECHR.

iv Legal certainty and non-retrospectivity:

- The rule against the retrospectivity of criminal law was upheld in the joint cases of R v Rimmington; R v Goldstein [2006] 2 All ER 257, HL.

v Fair hearing by an independent judiciary

- In Matthews v Ministry of Defence [2003] 1 All ER 689, HL the HL held that a section of a statute did not offend against the right to a fair trial under Article 6 ECHR, because it did not bar the courts from considering the case.

- In R (on the application of Anderson) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2002] 4 All ER 1089, HL the mandatory murder tariff was left in the hands of the Home Secretary, but this was subject to review by the courts as to whether the executive had breached Article 6 in affording the tariff.

vi The rule of law and substantive judgments:

- Traditionally judicial review has been restricted to the legality, rationality, and procedural propriety of the executive’s action, omission rather than the review of the content of its decision.

- In R (on the application of Al Rawi and others) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs and another [2006] EWCA C 1279, the CA held that the role of the courts has expanded in human rights cases to consider the proportionality of the decision, as well as its strict compliance with the law. This was a consequence of the Human Rights Act 1998.

F. The UK Legal System and the Rule of Law

Arbitrary and wide discretionary powers: Statutory provisions often afford public bodies the discretion to act in ways they consider to be reasonable. This discretion can be wide and arbitrary, which provides a threat to the rule of law.

Privileges, immunities and the rule of law: Equality before the law is potentially undermined by special powers, privileges and immunities from ordinary law that Parliament has granted.

The judicial extension of the criminal law: Dicey argued that ‘a man may with us be punished for a breach of law, but he can be punished for nothing else’; hence the courts should not be able to extend criminal offences laid down by parliament.

3.1.3 The Rule of Law Lecture – Hands on Examples

The following are some example essay questions, which you may find in an exam regarding the topic on the Rule of Law. Good answers should include reliance on a variety of arguments for and against a particular line of reasoning and show evidence of reading beyond lecture notes or a single academic textbook. Unlike other law topics, this one is fairly theoretical and hence various arguments based on legal scholarship should be revised in order to answer a question about the Rule of Law.

Q1 Outline the historical origins of the rule of law

Q2 Outline Dicey’s key features of a legal system based on the rule of law, consider criticisms of his theories.

Q3 Assess the continuing value or even the actual existence of the rule of law today

Q4 Consider how judges have interpreted the principles of the rule of law, with reference to recent case law

- Question 1

- A possible starting point is the Roman period where the Prince was considered to be above the law

- In the UK the Magna Cara 1215 asserted that the King was subject to the law of England

- Outline main principles within the Magna Carta

- Prohibitions del Roy (1607, published 1656 (1572-1616 12 Co Rep 63) Sir Edward Cooke held that the King could not act as judge and use his own reason to reach legal decisions

- Period of civil unrest in the 17th century where the King exceeded his powers

- The Barons reasserted the rule of law in the Petition of Rights 1628

- Habeas Corpus Act 1679 was introduced to prevent the King from detaining prisoners without trial or charge

- Bill of Right Act 1689 asserted the need for law to laws to be repealed or suspended only with parliamentary authority. The Monarch and the court’s were unable to subvert the right of the prisoner to Habeas Corpus.

- Question 2

- A.V. Dicey, writing inIntroduction to the Study of Law of the Constitution (1885) has been influential in establishing the rule of law within the 19th century and stating its content

- Three principles of the rule of law 1. Punishment requires the due process of law be followed, 2. Neither the King, nor the Prime Minister is above the law; 3. The rule of law is central to the UK constitution

- Jennings was one of Dicey’s most notable critics. In The Law and the Constitution, (1933), argued that Dicey failed to consider the powers of government, his focus was more upon constitutional relationships with the elements of the United Kingdom, than upon internal problems that the working classes were facing in the country at the time.

- For Jennings the rule of law would be all encompassing and consider the substantive nature of the law, whereas for Dicey, the rule of law merely concerned the narrow view that it was merely concerned with the governance of the acts of public officials, law makers and adjudicators.

- Question 3

- Short introduction to the rule of law, how was it defined by Dicey for example? Is that still relevant today?

- Refer to recent cases, e.g. R v Rimmington [2006] 1 Cr App R 17 and Sharma v Brown-Antoine [2006] UKPC 57 which both refer to Dicey’s principles of the rule of law.

- Consider anti-terrorism legislation, including Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 and Immigration Act 1971, that permit the Secretary of State to deport terrorist suspect when considered a threat to national security, shows and example of the use of wide and arbitrary discretionary powers that need to be kept in check by the rule of law.

- Also consider detention without trial in A and others v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2004] UKHL 56, and the requirement for the courts to overturn the discriminatory of the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 (since repealed).

- Importance of the right of Habeas Corpus particularly in relation to Guantanamo Detainees

- Does the Human Rights Act 1998 and the UK’s membership of the European Convention on Human Rights make the rule of law obsolete? No, since both of these things are currently under threat from the Conservative government.

- Question 4

- Use various principles of the rule of law and use case law to illustrate how they have been applied in practice.

- Punishment requires that the citizen has broken the law – the principle has been circumvented in anti-terrorist legislation, e.g. section1 of the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, which permitted indefinite detention of terror suspects without trial. Refer to case of A and others v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2004] UKHL 56,(Belmarsh case)

- Equality before the law – R v Mullen [2000] QB 520, the CA held that Mullen’s unlawful extradition undermined the administration of justice and his conviction was quashed, whatever the inconvenience. the rule of law must remain above the justification the state might attempt to use for acting outside of the law. The state was still subject the law on extradition proceedings.

- Citizen’s should have access to court to challenge the decisions of the state – In R (on the application of G) v IAT and another; R (on the application of M) v IAT and another [2005] 2 All ER 165, challenged the change of procedure for asylum claims which was implemented within the Asylum and Immigration [Treatment of Claimants] Act 2004. The final appeal stage of judicial review was replaced with a single high court judge who would review written submissions. This was found to be a sufficient recourse to a legal remedy to remain within the rule of law.

- The requirement of legal certainty –R v Rimmington; R v Goldstein [2006] 2 All ER 257, HLquestioned the certainty of common law. The case reiterated that common law was certain due to the precedent established on a case-by-case basis