By Law Teacher

7.1.1 Legislative Functions – Introduction

Introduction

Welcome to the seventh topic in this module guide – Legislative functions! Primary legislation constitutes UK Acts of Parliament, some of which include important constitutional rules in the absence of a codified constitution in the UK. The process of drafting primary legislation and the institutions involved in the process illustrate three key constitutional principles in context: parliamentary supremacy, the rule of law and the separation of powers.

The elected government takes a lead in the legislative process. Ministers and civil servants develop the policy behind the legislation, government lawyers draft Bills, ministers introduce Bills into Parliament and push them through the House of Commons and House of Lords. The Secretary of State often decides when a statute should come into force. Where the Crown Prerogative is involved, the Queen is required to give consent for the Bill to progress through Parliament. Bills require the royal assent to become law, in present times this is merely a formality.

At the end of this section, you should be comfortable with what legislative functions are. You will be able to identify the process of legislating, primary and secondary legislation and pre and post-legislative scrutiny. This section begins by discussing primary legislation. It then proceeds to identify who is the legislature and it discusses the drafting of bills. The section then goes on to look at pre-legislative and post-legislative scrutiny. There is then a discussion of the devolution and legislation. The section finally discusses administrative rule-making Royal prerogative powers and the need for reform. Finally, the section discusses recommendations for a more comprehensive approach to the whole set of royal prerogative powers.

Goals for this section:

To understand legislative functions.

To appreciate the different kinds of legislation.

To understand who is legislature.

Objectives for this section:

To be able to outline legislative functions.

To understand the role of the legislature.

To be able to understand scrutiny and drafting of bills.

7.1.2 Legislative Functions Lecture

I. Primary Legislation

Primary legislation constitutes UK Acts of Parliament, some of which include important constitutional rules in the absence of a codified constitution in the UK. The process of drafting primary legislation and the institutions involved in the process illustrate three key constitutional principles in context: parliamentary supremacy, the rule of law and the separation of powers.

d. Who is the Legislature?

The elected government takes a lead in the legislative process. Ministers and civil servants develop the policy behind the legislation, government lawyers draft Bills, ministers introduce Bills into Parliament and push them through the House of Commons and House of Lords. The Secretary of State often decides when a statute should come into force. Where the Crown Prerogative is involved, the Queen is required to give consent for the Bill to progress through Parliament. Bills require the royal assent to become law, in present times this is merely a formality.

e. Making Policy through Legislation

Legislation enables governments to create actions in relation to public policy. Policy is made at different speeds, sometimes the government wishes to change policies quickly. This requires the use of fast-tracked procedures to introduce legislation for certain policy imperatives.

Key Cases R v Davis [2008] UKHL 36; R (on the application of Bhatt Murphy (a firm) v The Independent Assessor [2008] EWCA Civ 755

f. The Drafting of Bills

A team of sixty parliamentary counsel (government lawyers) draft the bills for Parliament. Geoffrey Bowman, ‘Why is there a Parliamentary Counsel Office? (2005) 26 Statute Law Review, 69, 81 states

The process of legislative drafting needs someone who will stand back; who will ruthlessly analyse the ideas; who will question everything with a view to producing something that stands up to legislative scrutiny in Parliament and in the court; who will break concepts down to their essential components; and who will express them in easily digestible provisions and essential components… Counsel see themselves as technicians rather than policy makers. […]

A drafting style has been established in the UK that is different from the continental approach that is used in EU directives and regulations, as well as the legislation of other EU Member States. Acts of Parliament in the UK tend to be more detailed than codes in the civil law jurisdictions. Acts of Parliament are often criticised for being confusing and not easily accessible to the public, but there are a number of reasons for their complexity.

g. Pre-legislative Scrutiny of Draft Bills

Most Bills are introduced directly into Parliament, but some are first subjected to pre-legislative scrutiny. The Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee argued that pre-legislative scrutiny is ‘one of the best ways of improving legislation and ensuring that it meets the quality standard that Parliament and they public are entitled to expect’. (Ensuring Standards in the Quality of Legislation (HC 85 2013-14), [115]). It is considered to be one of the best methods to achieve a good quality of legislation and ensure the smooth passage of legislation through Parliament.

h. Bringing Legislation into Force

Pre-legislative scrutiny applies to a small number of bills, but all must pass through the main process. There is a tension during this process between the government wishing to get legislation through Parliament and the requirement for scrutiny of the legislation. Bills can be introduced into either the House of Lords (HL) or the House of Commons (HC). Non-controversial Bills usually begin in the HL.

i. Post-Legislative Scrutiny

In a number of policy areas, such as criminal justice, immigration, and social security the government has repeatedly resorted to new legislation in order to address ineffective legislation or legislation that leads to unintended consequences. The redrafting of legislation, however, fails to address underlying policy and administrative issues that may not be workable. It is possible for Parliament or government to subject legislation to post-legislative scrutiny, however, the process has been used rarely and in an unsystematic manner.

j. Devolution and Legislation

II. Secondary Legislation

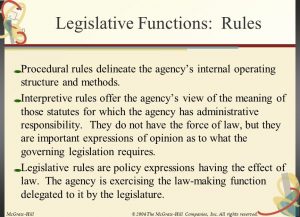

Delegated legislation is also referred to as ‘subordinate’ or ‘secondary’ legislation. The constitution allows the executive (Ministers) to create such legislation. This allows the government to create legislation on a large scale without the involvement of Parliament.

Statutory Instruments (SIs) are the most common form of secondary legislation. They derive their legitimacy through powers delegated to a minister or department in primary legislation. SIs must refer to the specific clauses within the primary legislation, which gives the government the power to draft secondary legislation. If provisions within secondary legislation are found to be inconsistent with their parent legislation or procedurally incorrect, they can be declared invalid by the courts.

The Need for Delegated Legislation

After 1918, there was concern amongst lawyers and politicians regarding the wide legislative powers of government departments. The Committee on Minister’s Powers concluded that unless Parliament was willing to delegate legislative powers, there would not be the capacity to pass the quantity of legislation that modern public opinion required. The Statutory Instruments Act 1946 aimed to provide greater legislative scrutiny for delegated legislation. There are a much greater number of Statutory Instruments passed each year than Public and General Acts.

Why is Delegated Legislation Important?

The time available in Parliament to enact new statutory rule is limited. Unless the procedure for considering Bills was streamlined, without SIs the Parliamentary machine would clog up. There is a necessity to make detailed regulations, such as those that relate to road traffic or social security which are entrusted to the relevant government department so long as there is Parliamentary oversight. Details contained in SIs are often technical and require the involvement of experts and professional bodies or commercial interests. The more technical the details of the legislation, the less suitable the legislation is for scrutiny by Parliamentarians who have little understanding of the subject matter of the legislation.

Types of Delegated Legislation

Frequently delegated legislation is criticised for providing powers to government ministers in excess of that which is necessary. Frequently powers are conferred broadly on government department to cover many eventualities. Certain Bills are proposed that are little more that skeleton Acts and many provisions are created through regulations which provide the executive with extensive powers and little parliamentary scrutiny is required of any of the powers conferred within the primary and secondary legislation.

Modern pressures particularly those associated with the economy require Parliament to delegate some powers in relation to taxation. In particular, the system of customs duties combined with the development of the EU has made necessary the delegation of power to give exemptions and reliefs from such duties. The Community Infrastructure Levy was a whole new system of taxation that was set up by delegated legislation under Part II of the Planning Act 2008.

The courts are only able to declare delegated legislation as ultra vires. Rights under the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA 1998) must also be protected by the courts. It is not for a Minister to determine his or her own powers, so courts are able to decide when a Minister is acting outside of them.

The Authority to Modify Acts of Parliament

Although it appears undesirable, Parliament has conferred bowers to Ministers to amend Acts of Parliament. Examples of such are found within the Scotland Act 1998 and the Government of Wales Act 2006. Some statutes go as far as allowing Ministers to modify existing and future Acts. Three examples of a delegated power to modify Acts of Parliament include

- Section 2(2) ECA 1972 authorised the making of Orders in Council and ministerial regulations to implement certain of the UKs obligations under EU Treaties.

- Section 10 HRA 1998 allows Ministers to amend primary legislation. When a superior court finds legislation to be incompatible with a right under the ECHR, Ministers or the Queen in Council may make remedial orders.

- Section 1 of the Legislative and Regulatory Reform Act 2006 enables ministers to amend or repeal Acts in order to reduce financial costs, administrative inconvenience or obstacles to efficiency. This power is subject to many conditions and qualifications.

The Public Bodies Act 2011 confers powers on ministers to abolish bodies specified in schedule 1 of the Act and to transfer such powers to government ministers, or other persons carrying out a public function.

F. Control and Supervision by Parliament

Since all delegated powers stem from statute, there are always the opportunity to scrutinise clauses that seek to delegate legislative powers at the committee stage. In 1992, the House of Lords appointed a committee to consider such clauses in Bills, now known as the Committee on Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform. It aims to discourage the granting of excessive powers through secondary legislation. In general, the SI is placed before Parliament and requires an affirmative resolution either before it is ‘made’, before it comes into effect, within a stated period, or it is subject to annulment by a resolution of either House. These cases include a positive procedure, an affirmative resolution of each House (or only the Commons for financial instruments). Two further procedures include the laying in draft before Parliament, subject to a resolution that no further action is taken or with no further provision for control. These two are negative procedures; no action is required by either House, unless there is some opposition to the SI.

Key Case: R (Stellato) v Home Secretary [2007] UK HL 5, [2007] 2 AC 270.

The House of Lords is usually granted the same powers of control as the House of Commons. The Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949 for by-passing the House of Lords only applies to Bills and not SIs. It is rare for the House of Lords to veto subordinate legislation, but they did in 1968 in relation to sanctions in Rhodesia. In 2000, the House rejected the Greater London Election rules regarding free postal delivery. The Lords have the power to veto a SI, unless it is financial, although this power is expected to be used rarely.

G. Challenges in the Courts

In general, delegated legislation can be challenged under Judicial Review. Unlike Parliament, Ministers’ powers are limited; an individual may question the validity of an instrument that it imposed against them.

Key Case: R v Home Secretary, ex p Javed, [2001] EWCA 789, [2002] QB 129 –

A SI may be challenged on the basis that:

- the content or substance is ultra vires,

- the SI was not created through the correct procedure.

The duty under s.3 HRA to interpret legislation in the light of Convention rights widens the scope for challenging delegated legislations. The HRA requires courts to strike down secondary legislation where it is not possible to interpret it in accordance with a Convention right. Courts cannot strike down secondary legislation where the primary legislation prevents this. Under s.4 HRA the court might declare a regulation incompatible with a Convention right.

Key Case: R v Environment Secretary, ex p Spath Holme Ltd [2001] 2 AC 349

The principle that no one can be deprived of access to the courts cannot be included within a SI unless Parliament has clearly legislated to this end.

Key Case: R v Lord Chancellor, ex p Witham [1998] QB 575

A number of cases have arisen out of various legislative regimes that impose restrictions on certain individuals who are suspected of having links to terrorists or rogue states. This prescription leads to the freezing of bank accounts and the prevention of trade, which has potentially serious consequences for an individual or organisation.

Key Case: Ahmed v HM Treasury [2010] UKSC 2, [2010] 2 AC 534

Key Case: Bank Mellat v HM Treasury (No 2) [2013] UKSC 39 [2013] 3 WLR 179

There is no general requirement for prior publicity of delegate legislation, but departments proposing a new instrument frequently make consultations of those who are deemed to have an interest in the legislation. Where there is a duty to consult the courts have established criteria for that consultation process that should be followed:

- it must be undertaken when the proposal is at a formative stage,

- there must be sufficient reasons given for the policy that is proposed so consultation is informed,

- there must be sufficient time for a response to be made,

- any feedback must be taken into account when decisions are made,

- fairness might require disclosure to interested parties.

Even when there is no duty to consult, common sense dictates that reference to specialists in a certain policy area can make valuable contributions to the formulation of policy and the form of the legislation. There is often consultation when there is no duty to do so.

H. Administrative Rule-Making

SIs are more flexible than primary legislation, but are often complex and expressed in formal language. There are also less formal methods of rule making, for example the Immigration Rules under the Immigration Act 1971.

Key Case: Odela v Home Secretary [2009] UKHL 25, [2009] 1 WLR 1230

Key Case: Pankina v Home Secretary [2010] EWCA Civ 7191, [2011] QB 376

Later cases have not yet clarified that status of the Immigration Rules¸ but it has been held in R v (Munir) v Home Secretary [2012] UKSC 32, [2012] 1 WLR 2192, that the Immigration Rules were not derived from the royal prerogative and that they were delegated legislation.

7.1.3 Legislative Functions Lecture – Hands on Examples

The following scenario aims to test your knowledge of the topics covered in the chapter on Primary and Secondary Legislation. The answers can be found at the end of this section. Make some notes about your immediate thoughts and if necessary, you can go back and review the relevant chapter of the revision guide. Working through exam questions helps you to apply the law in practice rather than just having a general understanding of the legal principles. This should help you be prepared for particular questions, which may be presented in the exam.

Scenario

Part A: The government wish to introduce a new government Bill to implement government policy that all under 7’s should receive free milkshakes in school. The government have called this Bill the Free Milkshake’s Bill 2016. A government MP who is also formally a nutritional expert is opposed to the Bill as she believes that offering children free milkshakes will be detrimental to their health. She requests the opportunity to be involved at the committee stage of this Bill, she wishes to amend the Bill so that children are provided with organic apple juice instead of milkshake. What is the likely outcome of this request and what is the process for the Free Milkshake’s Bill 2016 to pass into law?

Part B: Who are responsible for drafting of government bills? What are the skills that are required when drafting potential Acts of Parliament, where can they go wrong?

Part C: Is Parliamentary scrutiny of draft Bills sufficient to ensure that the public interest is being served in the creation of new legislation?

Part D: What are the reasons for delegated legislation being produced in addition to primary legislation? Is the process of scrutiny of secondary legislation sufficient?

Suggested Answers

A) The Free Milkshake’s Bill would go through the stages of bring legislation into force, starting with a first reading where the Bill is presented into Parliament in either the House of Lords or House of Commons. This is not an uncontroversial Bill, it is likely to have significant cost implications so it should begin in the House of Commons. After its second reading, the Bill will reach the Committee Stage. At this point the government MP who wishes to be part of the Committee is unlikely to be permitted to join as she has reservations against the Bill. To get Bill’s through Parliament, the whip system requires MP’s on the governments side to vote for the Bill and not present amendments at the Committee stage. Government MP’s risk their career if they attempt to make amendments to Bills at the Committee stage. IT is unlikely that the nutritional expert will be allowed by her party to join the Committee stage of the Bill reading. The Bill may also go to a Public Reading stage if it is considered relevant to do so. The next stage is the report stage, in which amendments may be proposed. An opposition MP may request an amendment at this point, all amendments have to be agreed in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, creating a possible ‘ping pong’ effect where the Bill bounces between the two houses attempting to achieve consensus. The next stage is the third reading. The final stage of the Bill is the royal assent which is a formality. Unless an opposition MP produces an amendment that is accepted by the government and both Houses, the Bill is likely to pass through Parliament without too many difficulties, despite the possible health consequences of providing free milkshake’s to under 7’s.

B) A team of around 60 parliamentary counsel who are government lawyers are responsible for drafting government Bills. There is a particular art to the drafting of Bills. It requires a drafter to break down policy matters into essential components, to predict what challenges might occur in court and address them during the drafting stage and produced a Bill that will withstand legislative scrutiny in its passage through Parliament. The UK drafting style varies from that of continental European codes and is usually more elaborate in its explanations. However, since 1999 all Bills have also included ‘explanatory notes’.

Drafting of Bills can go wrong if the are ‘over drafted’ offering too much detail or lack detail or are too broad giving rise to possible legal challenges in court and loopholes. The Computer Misuse Act 1990 is an example of a Statute that has been criticised for being drafted too broadly and has left loopholes in the legal provisions.

C) Parliamentary scrutiny often appears insufficient. There are a number of stages of possible scrutiny, but they are not always used. Pre-legislative scrutiny is one of the best methods of achieving quality legislation, but it is rarely used. The normal legislative process pressures government MP’s to vote with their party and hence dissention is strongly discouraged. Any amendments or votes against legislation must thus come from opposition parties, who are numerically smaller in Parliament than the majority government. Hence it is very difficult for Bills to be prevented from passing, the House of Lords are not able to block Bills, they may only postpone their passage.

D) Secondary or delegated legislation is created by government Ministers or civil servants, there is no need for it to go through the Parliamentary stages of approval. It is authorised through an enabling Act, which gives powers to the executive to create such secondary legislation as required to implement the finer details of government policy. There are around three time more pieces of secondary legislation than primary legislation and without such legislation, Parliament is unlikely to be able to produce sufficient legislative provisions to implement its policies. Scrutiny of secondary legislation is less formal. Acts which include provisions for delegated legislation can be scrutinised at the Committee Stage, but it is hard at this point to envisage exactly what secondary legislation might be created as the result of an Act of Parliament. The Committee on Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform seeks to prevent excessive powers being provided within delegate legislation. Further the Joint Committee on Statutory Instruments scrutinise all Statutory Instruments. Delegated legislation can also be subjected to judicial review, a court can find that a Minister has acted outside of his or her powers or procedurally incorrect. The courts can also strike down delegated legislation if it fails to conform to rights under the European Convention on Human Rights.