GUARDIAN PERMISSION AND WOMEN’S CONSENT

A widespread problem in many Muslim countries, especially in those marked by poverty, feudal structures, and/or large gaps in the status of social groups, is the conveying or selling of young women for economic gain or under political and other pressures. There is no unified position within the Islamic world on the legal role of parents or a guardian (wali) in contracting or agreeing to a marriage or on the rights of women to determine their own spouses, either within civil legal jurisprudence or under the shari’a law.

However, there is also no Islamic justification for forcing any woman to marry against her will or for preventing a mature woman from marrying as she chooses. Nonetheless, the actual practice throughout the Muslim world often excludes women from having any voice in the choice of their marriage partners, even though—given the enormous power Muslim society generally grants to husbands and their families—that decision will be of monumental importance to their prospects of happiness. Minimum consent of marriage of the guardian and women continues to vary among Muslim countries.

Iran: Many legal codes require the consent of the bride but undermine this with other provisions. For example, Iranian law stipulates that the official conducting the marriage read the conditions of the contract to both parties and that they separately sign each condition to indicate acceptance. However, according to a 2004 U.S. State Department report, previously unmarried females, even those over 18 years of age, first need either the consent of a father or grandfather or a court override.8

Turkey: The right of women to choose their own spouses needs to be secured such as this is regarded as a natural extension of the shari’a.

Tunisia: women who have reached the age of civil consent (20) must consent to their own marriages

8 U.S. Department of State. “Country Reports—Iran”: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2004/41721.htm, accessed 5 August 2005

Morocco: Recent reforms to the Family Law code universally require women’s consent. The extensive reforms to the Moudawwana in 2004 make Morocco a model case. Under Morocco’s new law, women become their own guardians on reaching majority, may conduct their own marriages, and may not be coerced into marriage under any circumstances. While significant challenges in implementation remain, Morocco’s exemplary family law code grants Moroccan women rights of consent in marriage that are a true model for the Islamic world.

Iraq: Prior to 1959, “marriage contracts concluded by coercion” were considered void so long as they had not been consummated.10

Algeria: Forced marriage is not permitted, but perpetrators face no penalties. Many young women face family and community pressures to marry against their will and have no or only limited channels through which to voice dissent. Social support networks that might aid the woman in such cases, as well as the backing of an accessible formal or informal justice system, are generally lacking.

Indonesia: Require the bride’s consent (or at least her lack of objection), but provide no realistic way for her to make such an objection known and no clear mechanism for escaping an illegal marriage (e.g., annulment).11

Malaysia: It is illegal to prevent a woman of 16 or a man of 18 and above from contracting a valid marriage. Doing so can be punished with a fine, imprisonment, or both; yet the law recognizes the wali’s consent as a requirement in marriage, but his refusal may be overruled by the courts.12

9 L’Association Démocratique des Femmes du Maroc (ADFM), 2004, accessed 13 April 2005

10 Emory University Law School.

11 Knowing Our Rights, p. 91

12 Knowing Our Rights, p.72

Table 3: Guardian Permission: Summary

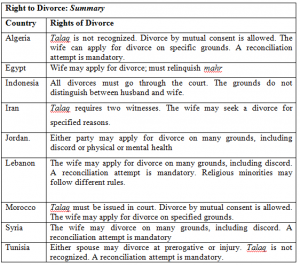

RIGHT OF DIVORCE

In many countries in the Islamic world, men have possessed a unilateral and unconditional right to divorce. In these same countries, women are often not only not afforded that right but, if they are allowed the right of divorce at all, must resort to the courts to divorce their spouses, where they confront innumerable social, legal, and bureaucratic obstacles. In many Islamic countries, women are often at a massive disadvantage compared to men in such matters as financial support, child custody, child visitation and child guardianship, and subsequent remarriage. In Tunisia, Malaysia, Iran, and Yemen, the law requires that all divorces be settled in a court of law. While laws vary considerably in the degree to which women may seek divorce and on what grounds men may seek divorce, most of these countries mandate that the procedure be conducted in a court of law. For instance,

Iran: Here talaq is recognized, the husband can divorce his wife without citing any reasons. However, divorce is permissible only through the courts and any independent pronouncement of talaq made on the part of the husband is considered immaterial before the court of law. Moreover, the registrar can only register a divorce after permission has been issued from a court and after any mahr, maintenance, and/or wages for housework have been paid to the wife. The law is interpreted to mean that no court can prevent a man from divorcing his wife; however, all her financial rights must be settled prior to the separation.

Tunisia. Under Article 31 of the Personal Status Code, divorce by mutual consent (or Mubarat) is recognized. Divorce is possible only through the court and only after the judge has made reconciliation efforts. Article 31 also establishes equal grounds for husband and wife, including “at the will of the husband or at the request of the wife”.

Egypt: In 2000, Egypt enacted a law that allowed women the right to obtain a divorce from their husbands on the grounds of incompatibility. The divorce is granted on the wife’s return of her mahr. Prior to the new law, a husband could file for divorce without even informing his wife, while the wife needed conclusive proof and independent corroboration of physical abuse by the husband.

Syria: Syrian law of Personal Statute (1953) put the husband’s motive for divorcing his wife under judicial scrutiny by financially punishing arbitrary use of talaq.13 The Syrian Law of Personal Statute provides that, when a husband divorces his wife without adequate cause, he must pay her financial compensation to the equivalent of one year’s maintenance.

Indonesia. Under the Marriage Law, all divorces must go through the court. A husband married under Muslim laws must provide the religious court with a written notification of his intention to divorce, which must include his reasons for wishing to do so. If the reasons accord with one of the eight grounds available to husbands and wives, both parties are called separately for reconciliation meetings with counselors. If reconciliation fails, the court will call the parties to witness the divorce.”14. Indonesian divorce codes “do not distinguish between husband and wife.”

13 Emory University Law School, “Syria, Syrian Arab Republic”: http://www.law.emory.edu/IFL/legal/syria.htm, accessed 20 June 2005.

14Knowing Our Rights, pp. 262 and 269

MAINTENANCE

Under Muslim law a man must maintain his wife and children. The husband is under a duty to maintain his divorced wife during the period of iddat. Maintenance continues to vary among the Muslim countries.

Iraq: Post-Divorce Maintenance/Financial Arrangements: husband obliged to maintain divorce (even if nashiza) during iddat; 1983 legislation provides that repudiated wife has right to continue residing in marital home without husband for three years, so long as she was not disobedient, did not agree to or request divorce, and does not own house or flat of her own.

Morocco :Post-Divorce Maintenance/Financial Arrangements: husband obliged to maintain divorce (even if nashiza) during iddat; 1983 legislation provides that repudiated wife has right to continue residing in marital home without husband for three years, so long as she was not disobedient, did not agree to or request divorce, and does not own house or flat of her own .

Tunisia: Post-Divorce Maintenance/Financial Arrangements: husband obliged to provide maintenance during iddat or, if there is an infant, until the child is weaned; if divorce was husband’s will, judge may determine what financial compensation is due to wife (or vice versa if divorce was at request of wife).

Senegal: Post-Divorce Maintenance/Financial Arrangements: in case husband sought divorce on grounds of incompatibility or incurable illness of wife, obligation to maintain is transformed to obligation to pay alimony; in case divorce is judged to be exclusive fault of one party, judge may grant other party compensation.