By Law Teacher

8.1 Economic Torts – Introduction

Welcome to the first lesson of the eighth topic in this module guide – Economic Torts! Tort recognises that, as with personal integrity or property, one’s business or livelihood can be open to negligent or intentional acts. As such, the law provides a framework by which malicious actors may be prevented from destroying an individual financially.

At the end of this section, you should be comfortable with the two primary categories of economic tort: procuring a breach of contract; and causing a loss by unlawful means. This section begins by looking at each of these categories, their necessary elements and the defences to them. Attention is then turned to conspiracy, a useful consideration here since it is often ancillary to the two primary categories of economic tort.

Goals for this section:

- To understand and be able to apply the law relating to economic torts.

Objectives for this section:

- To know the law applicable to defendants who procure a breach of contract.

- To understand when a loss has been caused by unlawful means.

- To be able to identify whether a defence to an economically tortious act applies in certain factual circumstances.

- To know whether a conspiracy has taken place.

8.2 Economic Torts Lecture

Tort law provides a framework for dealing with negligent or intentional acts done against a person’s business or livelihood.

The economic torts can be split into two primary categories: procuring a breach of contract and causing loss by unlawful means. Conspiracy is also discussed below, and whilst this is a separate tort, it can generally be regarded as ancillary to the two primary torts of inducing breach and unlawful interference.

Harsh business practices do not form the basis for a tort. This can be seen in Mogul Steamship Co Ltd v McGregor, Gow & Co [1889] LR 23 QBD 598. The exception to this rule is conspiracy to injure, discussed below, but even this exception is rarely applied.

Inducing a Breach of Contract

Contracts form the backbone of business operations. A given organisation will have multiple contracts with the businesses which provide it with stock or raw materials, and everyone who provides services to it will be contracted to do so. If these contracts are not fulfilled as each side promises they will, this can have severe and unanticipated negative effects for both parties. Tort law can step in to assist here, and in particular can provide a course of action against any third parties for breaching their contract, whereas contract law cannot.

The root of the tort can be found in Lumley v Gye [1853] 2 E & B 216 where the court discussed that under contract, damages might be limited in a way which would mean they failed to properly reflect the claimant’s harm. They thus found it just, under the principle of full compensation, to create an action against the inducer.

The Tort Requires Malice

It should be noted that the tort requires malice on the part of the defendant. Rather than active hostility, this refers to the concurrence of two things – the defendant must know that they are affecting the discharge of another contract, and they must intend to do so. Thus a defendant who unknowingly offers a better contract to a third party than the one they are already in will not be liable.

Regarding intention, a defendant who carelessly causes another to breach their contract will not suffice, as in Cattle v Stockton Waterworks Co [1975] LR 10 QB 453.

Intention does not need to be particularly concerted – it will suffice if a defendant knowingly creates a risk of breach being induced, even if they are indifferent as to whether the breach is actually made or not. The overriding principle and this phenomenon of contract can be seen in Torquay Hotel Co Ltd v Cousins [1969] 2 Ch 106 where the court summarised three essential elements of the tort:

- There must be interference with the execution of a contract (even if that interference doesn’t result in breach);

- The interference must be deliberate; and

- The interference must be direct.

Since these three elements existed in the case at hand, the tort had occurred, despite the existence of a force majeure clause.

Regarding knowledge, a defendant’s knowledge that their actions will cause a breach of contract is not enough to demonstrate intent – there must be evidence to show that the defendant’s primary aim was to cause a breach of contract, rather than that being a secondary effect of an action with an altogether different intent. This can be seen in OBG v Allen [2007] UKHL 21 where the defendants’ primary intention was not to cause breach and so the claim failed.Knowledge of the other contract does not need to be particularly detailed, as per JT Stratford & Son Ltd v Lindley [1965] AC 269.

The tort is also one of inducing a third party away from a contract they are already in, rather than putting a better offer on the table when the third party is merely considering what deal they will take. This can be witnessed in Allen v Flood [1898] AC 1.

Damage is Required

It is not enough for a defendant to have merely induced breach of contract – the claimant must show some loss has stemmed from the action. However, this does not necessarily mean that quantifiable loss needs to have arisen from the breach of contract, see Exchange Telegraph Co v Gregory & Co [1896] 1 QB 147.

Defences

A defendant can argue that their actions were justified as a defence to this tort. However, the bar for advancing this defence is understandably high, so as to avoid eroding the utility of the tort, South Wales Miners’ Federation v Glamorgan Coal Co Ltd [1905] AC 239.

A particular form of justification can be employed when the defendant can demonstrate that they are exercising a right which trumps that of the claimant. This is illustrated in Edwin Hills & Partners v First National Finance Cop [1989] 1 WLR 225.

Causing Loss by Unlawful Means

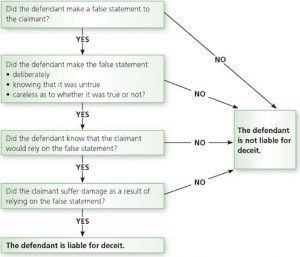

It is also a tort to interfere with the claimant’s trade using unlawful means. The tort includes two primary elements – the defendant must have acted unlawfully in their interference with the claimant’s trade, and they must have done so with the intent to injure the claimant.

Intention to Harm

It is necessary for a claimant to demonstrate that a defendant has the intent to injure their business via their unlawful act. Sometimes it is not clear whether this requirement has been fulfilled – a defendant might take an unlawful act which harms the claimant, but which isn’t inherently aimed at the claimant.

The intention element was subject to significant discussion in Douglas v Hello! Ltd (No. 3) [2005] EWCA Civ 595 where Lord Nicholls described the intent element as follows:

“Intentional harm […] satisfies the mental ingredient of this tort. This is so even if the defendant does not wish to harm the claimant, in the sense that he would prefer that the claimant were not standing in his way”

Unlawful Means

The unlawful act criterion was provided in OBG v Allen [2007] UKHL 21 where Lord Hoffman explained: “Unlawful means consists […] of acts intended to cause loss to the claimant by interfering with the freedom of a third party in a way which is unlawful […] and which is intended to cause loss to the claimant. It does not in my opinion include acts which may be unlawful against a third party but which do not affect his freedom to deal with the claimant.”

- Violence and threats of violence provide a primary example of how the tort operates, as in Tarleton v McGawley [1793] 170 ER 153.

- Fraud and misrepresentation are also covered by this tort, as per National Phonograph Co Ltd v Edison Bell Co Ltd [1908] 1 Ch. 335. A more modern version of fraud can be seen in Lonrho v Fayed [1990] 2 QB 479.

- In a crossover between the torts of inducing breach and unlawful interference, there is a precedent of breaching contract or threatening breach of contract constituting the required unlawful act. This can be seen in Rookes v Barnard [1964] UKHL 1.

Whilst non-violent crime can form the basis of unlawful interference, the requirement remains that it must be aimed at the claimant. This can be seen in Lonrho Ltd v Shell Petroleum Co Ltd [1982] AC 173 (also discussed as a matter of employers’ statutory duties.)

Defences

Unlike inducing breach, the defence of justification cannot be employed for unlawful interference, as per Rookes v Barnard. In short – if an act is unlawful it cannot be justified. The exception to this rule is where the unlawful act is threatening or causing breach, but the defendant has a pre-existing legal right which equals or overrides the right he is interfering with (for an example of this, see Edwin Hills & Partners v First National Finance Cop above.)

Conspiracy

The law recognises situations in which a group of actors come together with the aim of harming the claimant’s business or trade, via unlawful means or otherwise.

Conspiracy to commit an economic tort is designed to allow a claimant to bring a case against a group of malicious plotters who would otherwise avoid liability, because their individual actions are not in and of themselves tortious, or because only one of them actually took the tortious act.

Conspiracy to Injure

This tort is essentially an agreement between several actors to act together to injure the claimant’s business interests (which results in damage, mere agreement is not enough.)

It is key that the conspirators’ actions are aimed at the claimant, rather than merely being a genuine attempt to further their own business interests. In other words, malice is required. Notably, however, this tort does not necessarily an illegal act (such as breach of contract or unlawful activities).

It should be noted that this tort is rarely applied and highly controversial, since essentially it imports liability on a group of people for taking perfectly legal actions. In both Lonrho v Shell and Lonrho v Fayed, the courts have confirmed that this tort still exists, but have noted that the bar for finding that a legal business practice is illegitimate is extremely high.

This tort is illustrated in Quinn v Leathem [1901] AC 496 where a series of actions was held to be conspiracy to injure.

This can be contrasted with Crofter Hand Woven Harris Tweed Co v Veitch [1942] AC 435. This claim failed – the courts regarded the actions of the defendants to be legitimate, since the object of their actions was to best benefit their members, rather than to harm the claimants.

The bar for finding this tort is extremely high; in other words: the justification defence is very easy to advance.

Conspiracy Using Unlawful Means

Conspiracy using unlawful means is a much simpler affair – since the defence of justification doesn’t exist, there will be no need to distinguish between legitimate acts of economic competition and malicious conduct. Instead, it will be sufficient to show that a group of actors conspired to use unlawful means to inflict economic harm upon the claimant.

The nature of this tort is essentially exactly the same as the tort of unlawful interference discussed above, to the extent that the above mentioned Rookes v Barnes provides the key case.

8.3 Economic Torts Lecture – Hands on Examples

Question:

Jed runs a large whisky distillery called ‘West Tipple Industries’ on the isle of Islay in Scotland.

He receives ingredients for his whisky from three different suppliers. He receives malted barley from Ziegler Malts, fresh spring water from Lyman Springs, and a colouring agent from Seaborn Culinary Products.

One day, a new distillery starts up on the isle – the New Republic Distillery, run by Ainsley. Ainsley realises that West Tipple Industries are her main competitor, and concocts a plan to further her business interests.

Firstly, she knows that Ziegler Malts are the only source of malted barley in the area, and that they have a relatively small capacity. At the moment, Ziegler Malts supply both West Tipple Industries and the New Republic Distillery. After talking with her fellow board members and securing funds from an investor, Ainsley goes to Ziegler Malts and offers them a new deal – at the end of their current contract with West Tipple Industries, they will agree to sell the entirety of their stock to New Republic. Ainsley plans to use what she needs in her own distillery, and then sell the rest of the malted barley to the other distilleries in Scotland. She does not plan to supply West Tipple Industries (who will have to buy their malts from other sources.)

Secondly, she goes to Lyman Springs and makes them an offer. Lyman Springs have a contract to supply West Tipple Industries for the next twenty years. Ainsley makes them an alternative offer – if they break their contract and supply New Republic, she will buy out the entirety of their contract, and pay any of their legal fees they attract for breaching their contract.

Thirdly, she approaches Seaborn Culinary Products. They are a supplier of West Tipple Industries, but they have no standing contract with them. Seaborn pride themselves on their loyalty, and despite a better offer from Ainsley, they remain resolute in their intention to keep supplying West Tipple Industries with their entire output. This means that Ainsley will have to source her colouring agents from outside of Islay – an expensive endeavour. Instead, she pays local thugs to beat up the board members of Seaborn Culinary Products, and deliver the message that worse is to come if they don’t stop supplying West Tipple Industries at the end of their current contract, and make New Republic their new customer.

It isn’t long before Jed notices that things are not well on Islay. He contacts his suppliers and learns about what has been going on.

Advise Jed on what economic torts have been committed by the New Republic Distillery.

Answer:

There are three different potentially tortious actions which take place between Ainsley and the various suppliers on Islay.

The first is the deal between Ziegler Malts and West Tipple Industries. There is a notable, but slim, chance that her actions will be regarded as conspiracy to injure, as in Quinn v Leathem [1901] AC 496. Ainsley talks with her board and an investor, suggesting that she is not acting alone, so the multiple actors requirement is fulfilled. This is not a matter of unlawful means conspiracy, since no contracts will be breached, Ainsley has simply offered an alternative business proposition to Ziegler Malts once their current contract with West Tipple Industries is complete (as in Allen v Flood [1898] AC 1.)

Her actions will indeed harm West Tipple Industries – she is taking away the source of a vital ingredient, and forcing Jed to source it from further afield, to his detriment. However, Ainsley’s actions can be likened to those of the defendant in Crofter Hand Woven Harris Tweed Co v Veitch [1942] AC 435 – whilst harsh and undiplomatic, they clearly advance her own business interests. She is sourcing an ingredient for her own business, and intends to sell the surplus on – itself a legitimate business practices. Thus, although monopolistic, her actions can be considered non-tortious, as in Mogul Steamship Co Ltd v McGregor, Gow & Co [1889] LR 23 QBD 598. This claim will therefore likely fail.

The second deal is with Lyman Springs. This is potentially a case of inducing a breach of contract. This is relatively straight forward case of enticement, as in Lumley v Gye [1853] 2 E & B 216. Ainsley knows of the other contract, and intends for it to be breached, hence her offer of paying Lyman Springs’ legal fees. Even though she might not know the ins and outs of the contract with West Tipple Industries, this will not form an obstacle – it is enough that she has a basic knowledge of it, as per JT Stratford & Son Ltd v Lindley [1965] AC 269. Whilst it will be possible for West Tipple to find an alternative supplier, the court is likely to infer that there has been some damage to West Tipple from the breach. As illustrated by Exchange Telegraph Co v Gregory & Co [1896] 1 QB 147, the extent of the damage stemming from the induced breach need not be egregious. The fact that West Tipple has had a 20 year contract taken out from under them will be of significant inconvenience, thus likely fulfilling this requirement. This claim will therefore likely succeed.

The third ‘deal’ is with Seaborn Culinary Industries. This is likely a case of causing loss by unlawful means. Ainsley’s actions clearly are aimed at West Tipple Industries – she uses violent intimidation to remove one of their business partners. Just as the claimant’s loss was the defendant’s gain in Douglas v Hello! Ltd (No. 3) [2005] EWCA Civ 595, West Tipple Industries’ loss is New Republic’s gain. Although not as dramatic as firing a cannon, Ainsley’s actions are similar to those in in Tarleton v McGawley [1793] 170 ER 153 – except the violence is aimed at a supplier, rather than a customer. Thus, there is an unlawful act, and it is aimed disrupting West Tipple’s business practices. A claim for unlawful interference will likely succeed (along claims for various personal torts and criminal liability.)