By Law Teacher

Introduction

Trespass to the person means a direct or an intentional interference with a person’s body or liberty. A trespass which was also a breach of the King’s peace, however, fell within the jurisdiction of the King’s courts, and in course of time the allegation that the trespass was committed vi et armis (By force and arms) came to be used as common form in order to preserve the jurisdictional propriety of an action brought in those courts, whether or not there was any truth in it.

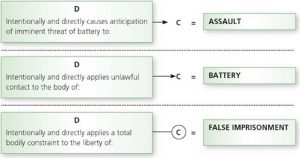

There are three main forms of trespass to a person, namely, assault, battery and false imprisonment and their common element is that the wrong must be committed by “direct means”. Any direct invasion of a protected interest from a positive act was actionable subject to justification. If the invasion was indirect, though foreseeable, or if the invasion was from an omission as distinguished from a positive act, there could be no liability in trespass though the wrong-doer might have been liable in some other form of action. The principal use today of these torts relates not so much to the recovery of compensation but rather to the establishment of a right, or a recognition that the defendant acted unlawfully. These torts are actionable without proof of damage (or actionable per se), they can be used to protect civil rights, and also will protect a person’s dignity, even if no physical injury has occurred (for example the taking of finger prints).

Acts of trespass to the person are generally crimes as well as torts. Criminal proceedings may lead to compensation of the victim by the offender without a separate civil action, for since 1971 the criminal courts have had power to order an offender to pay compensation to his victim, and the court is now required to give reasons, on passing sentence, if it does not make a compensation order. The law has now become more complicated in the area o conduct covered by the trespass torts. For example, an adviser may have to consider civil liability under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 which is in other respects much wider than trespass.

Assault And Battery

An assault is an attempt or a threat to do a corporeal hurt to another, coupled with an apparent present liability and intention to do the act. Battery is the intentional and direct application of physical force to another person. Actual contact is not necessary in an assault, though it is in a battery. But it is not every threat, when there is no actual personal violence that constitutes an assault; there must, in all cases, be the means of carrying the threat into effect. With respect to battery, assault can be defined as an act of the defendant which causes the claimant reasonable apprehension of the infliction of a battery on him by the defendant. Thus, Battery occurs where there is contact with the person of another, and assault is used to cover cases where the claimant apprehends contact.

The intention as well as the act makes an assault. Therefore, if one strikes another upon the hand, or arm, or breast in discourse, it is no assault, there being no intention to assault; but if one , intending to assault, strikes at another and misses him, this is an assault; so if he holds up his hand against another, in a threatening manner, and says nothing, it is an assault. Mere words do not amount to an assault. But the words which the party threatening uses at the time may either give gestures such a meaning as may make them amount to an assault, or, on the other hand, may prevent them from being an assault. Assault of course requires no contact because its essence is conduct which leads the claimant to apprehend the application of force. In the majority of cases an assault precedes a battery, but there are cases the other way around like a blow from behind inflicted by an unseen assailant. It was said before that some bodily movement was required for an assault and that threatening words alone were not actionable, which was rejected by the House of Lords in R. vs. Ireland. Hence, threats on the telephone may be an assault provided the claimant has reason to believe that they may be carried out in the sufficiently near future to qualify as “immediate”. The House of Lords have more recently stated that an assault can be committed by words alone in R v Ireland [1997] 4 All ER 225, and the Court of Appeal in R v Constanza [1997] Crim LR 576.

A battery includes an assault which briefly stated is an overt act evidencing an immediate intention to commit a battery. It is mainly distinguishable from in an assault in the fact that physical contact is necessary to accomplish it. It does not matter whether the force is applied directly to the human body itself or to anything coming in contact with it. Thus, to throw water at a person is an assault; if any drops fall upon him it is a battery. Battery requires actual contact with the body of another person so a seizing and laying hold of a person so as to restrain him; spitting on the face, taking a person by the collar, are all held to amount to battery.

Important Cases Relating To Assault And Battery

Thomas V Num [1985] 2 All Er 1

The plaintiffs were members of a branch union of the National Union of Mineworkers (the NUM). In March 1984 the branch union voted to support strike action against the Mineworkers’ employer (the NCB) and in May the national executive of the NUM indorsed proposals by various branch unions for strike action and set up a coordinating committee to coordinate industrial action against the NCB, including the co-ordination of secondary picketing by branch unions outside their respective areas. In November the plaintiffs decided not to carry on with the strike and returned to work at their mines. However, the presence of 60 to 70 pickets outside the colliery gates each day and the accompanying demonstrations and abusive and violent language made it necessary for working miners, including the plaintiffs, to be brought into the collieries by vehicles and for the police to be present. The plaintiffs sought interlocutory injunctions against the branch union, its executive officers and trustees, and against the NUM and its coordinating committee. The plaintiffs contended, inter alia, that the picketing at the colliery gates was an actionable tort because it involved criminal offences under s 7 of the Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act 1875, such as using violence to or intimidating other people, persistently following other people, and watching and besetting the place of work of other people, and (ii) that in any event the picketing at the colliery gates was an actionable tort either as an assault, an obstruction of the highway, an unlawful interference with contract or intimidation to compel the plaintiffs and other working miners to abstain from working.

And it was held that:

(1) It did not follow that because picketing was an offence under section 7 of the 1875 Act it was therefore tortious, since in order to establish an offence under section 7 it was necessary first to show that the picketing amounted to a tort.

(2) The picketing at the colliery gates was not actionable in tort either (a) as an assault, since working miners were in vehicles and the pickets were held back from the vehicles by the police and therefore there was no overt act against the working miners, or (b) as obstruction of the highway, since entry to the collieries was not physically prevented by the pickets and in any event if there was an obstruction it was not actionable at the suit of the plaintiffs because it did not cause them any special damage, or (c) as an unlawful interference with contract, since the picketing did not interfere with the performance of a primary obligation under the plaintiffs’ contracts of employment with the NCB. Accordingly, the plaintiffs could not complain on any of those grounds that the picketing and demonstrations were tortuous.

(3) However, on the principle that any unreasonable interference with the rights of others was actionable in tort, the picketing was tortious if its effect was that the working miners were being unreasonably harassed, in the exercise of their right to use the highway for the purpose of entering and leaving their place of work, by the presence and behaviour of pickets and demonstrators. Since the plaintiffs had the right to use the highway to go to work and since the picketing by 60 to 70 pickets in a manner which required a police presence was intimidatory and an unreasonable harassment, the picketing at the colliery gates amounted to conduct which was tortious at the suit of the plaintiffs.

Per curiam. Mass picketing, ie picketing which by sheer weight of numbers blocks the entrance to premises or prevents the entry thereto of vehicles or people, is both common law nuisance and an offence under section 7 of the 1875 Act.

But the judgement stated that the defendants are entitled to the immunity provided by section 13 of the Act of 1974 which follows that the plaintiffs have not shown an arguable case against these defendants and thus, the judge dismissed the plaintiff’s application.

Wilson V Pringle [1986] 2 All ER 440

The plaintiff and the defendant were two schoolboys involved in an incident in a school corridor as the result of which the plaintiff fell and suffered injuries. The plaintiff issued a writ claiming damages and alleging that the defendant had committed a trespass to the person of the plaintiff. In his defence the defendant admitted that he had indulged in horseplay with the plaintiff and on the basis of that admission the plaintiff applied for summary judgment under RSC Ord 14. The registrar refused to enter judgment but on appeal by the plaintiff the judge held that the defendant had admitted that his act had caused the plaintiff to fall and in the absence of any allegation of express or implied consent the defence amounted to an admission of battery and consequently an unjustified trespass to the person. He accordingly gave the plaintiff leave to enter Judgment. The defendant appealed to the Court of Appeal, contending that the essential ingredients of trespass to the person were a deliberate touching, hostility and an intention to inflict injury, and therefore horseplay in which there was no intention to inflict injury could not amount to a trespass to the person. The plaintiff contended that there merely had to be an intentional application of force, such as horseplay involved, regardless of whether it was intended to cause injury.

Held – An intention to injure was not an essential ingredient of an action for trespass to the person, since it was the mere trespass by itself which was the offence and therefore it was the act rather than the injury which had to be intentional. However, the intentional act, in the form of an intentional touching or contact in some form, had to be proved to be a hostile touching, and hostility could not be equated with ill-will or malevolence, or governed by the obvious intention shown in acts like punching, stabbing or shooting or solely by an expressed intention, although that could be strong evidence. Whether there was hostility was a question of fact in every case. Since the defence did not admit a hostile act on the part of the defendant there were liable to judicial trial issues which prevented the entry of summary judgment. The appeal would therefore be allowed, and the defendants given unconditional leave to defend.

Per Curiam. Where the immediate act of touching does not of itself demonstrate hostility the plaintiff should plead the facts alleged to do so.

Garcia V. United States, 469 U.S. 70 (1984)

REHNQUIST, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which BURGER, C. J., and WHITE, BLACKMUN, POWELL, and O’CONNOR, JJ, joined. [469 U.S. 70, 71] STEVENS, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which BRENNAN and MARSHALL, JJ., joined.

REHNQUIST, J. delivered.

Petitioners assaulted an undercover United States Secret Service agent with a loaded pistol, in an attempt to rob him of $1,800 of Government “flash money” that the agent was using to buy counterfeit currency from them. They were convicted of violating 18 U.S.C. 2114, which proscribes the assault and robbery of any custodian of “mail matter or of any money or other property of the United States.” The United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit affirmed petitioners’ convictions, over their contention that 2114 is limited to crimes involving the Postal Service.718 F.2d 1528 (1983). We granted certiorari, 466 U.S. 926 (1984), to resolve a split in the Circuits concerning the reach of 2114, and we affirm.

Agent K. David Holmes of the United States Secret Service posed as someone interested in purchasing counterfeit currency. He met petitioners Jose and Francisco Garcia in a park in Miami, Fla. Petitioners agreed to sell Holmes a large quantity of counterfeit currency, and asked that he show them the genuine currency he intended to give in exchange. He “flashed” the $1,800 of money to which he had been entrusted by the United States, and they showed him a sample of their wares – a counterfeit $50 bill.

Wrangling over the terms of the agreement began, and Jose Garcia leapt in front of Holmes brandishing a semiautomatic pistol. He pointed the pistol at Holmes, assumed a combat stance, chambered a round into the pistol, and demanded the money. While Holmes slowly raised his hands over his head, three Secret Service agents who had been watching from afar raced to the scene on foot. Jose Garcia dropped the pistol and surrendered, but Francisco Garcia seized the money belonging to the United States and fled. The agents arrested Jose Garcia on the spot, and pursued and later arrested Francisco Garcia as well.

Petitioners were convicted in a jury trial of violating 18 U.S.C. 2114 by assaulting a lawful custodian of Government money, Agent Holmes, with intent to “rob, steal, or purloin” the money. That section states in full:

“Whoever assaults any person having lawful charge, control, or custody of any mail matter or of any money or other property of the United States, with intent to rob, steal, or purloin such mail matter, money, or other property of the United States, or robs any such person of mail matter, or of any money, or other property of the United States, shall for the first offense, be imprisoned not more than ten years; and if in effecting or attempting to effect such robbery he wounds the person having custody of such mail, money, or other property of the United States, or puts his life in jeopardy by the use of a dangerous weapon, or for a subsequent offense, shall be imprisoned twenty-five years.”

Haystead V Director Of Public Prosecutions [2000] 3 ALL ER 850

The defendant Haystead had punched W twice in the face while she was holding her child, and as a direct result of that the child fell from her arms and hit his head on the floor. Counsel for the defendant submitted that in order to have committed the actus reus of battery in the offence of assault against the child by beating, the defendant had to have used force directly to the child’s person, that a direct application of force required the defendant to have had direct physical contact with the complainant either through his body, for example, a punch, or through a medium controlled by his actions, for example, a weapon, and that was not made out.

The court considered that the right approach was set out in Smith and Hogan, Criminal Law (9th edition (1999) p406), where it was said:

“Most batteries are directly inflicted, as by D striking P with his fist or an instrument, or by a missile thrown by him, or by spitting upon P. But it is not essential that the violence should have been so directly inflicted”. Thus Stephen and Wills JJ thought there would be a battery where D digs a pit for P to fall into, or as in Martin (1881) 8 QBD 54, he caused P to rush into an obstruction. “It is submitted that it would undoubtedly be a battery to set a dog on another. If D beat O’s horse causing it to run down P, this would be battery by D. “No doubt the famous civil case of Scott v Shepherd (1773) 3 Wils 403; (1773) 96 ER 525 is equally good for the criminal law. D throws a squib into a market house. First E and then F flings the squib away in order to save himself from injury. It explodes and injures P. “The acts of E and F are not ‘fully voluntary’ intervening acts which break the chain of causation. This is battery by D.” The court said that approach was right subject to the qualification that there might be some cases which could be explained because they were in truth an infliction of grievous bodily harm without an assault.

But it was not necessary to find a dividing line between cases where physical harm was inflicted by assault and where it was not, because even if counsel for the defendant’s definition of battery was correct, that test was made out on the facts of the case. W’s movements letting go of the child was a direct result of the defendant punching her. There was no difference between where he used her as a medium and where a weapon was used as a medium, save that in the latter case the offence involved intention, whereas in this case the defendant was reckless. Therefore the offence was made out and the appeal would be dismissed. An act by an assailant could constitute battery where it indirectly, through the medium of a third party, caused injury to the victim. The Queen’s Bench Divisional Court so held when dismissing an appeal by Haystead by way of case stated by Justices against their decision to convict him of an assault by beating, contrary to section 39 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988.

The Famous Rodney King Case

The 1991 beating of Rodney G. King by Los Angeles, California, police led to state and federal criminal prosecution of the law enforcement officers involved in the assault, a civil jury award of $3.8 million to King for his injuries, and major reforms in the Los Angeles police department. In addition, the April 1992 acquittal of the white police officers for the beating of King, an African American, touched off riots in Los Angeles that rank as the worst in U.S. history. The controversy surrounding each of these actions raised the issues of race, racism, and police brutality in communities throughout the United States.

On the evening of March 3, 1991, Rodney King was driving his automobile when a highway police officer signaled him to pull over to the side of the road. King, who had been drinking, fled, later testifying that he was afraid he would be returned to prison for violating his parole. A high-speed chase ensued with a number of Los Angeles police officers and vehicles involved. The police eventually pulled King over. After King got out of his car, four officers — Stacey C. Koon, Laurence M. Powell, Timothy E. Wind, and Theodore J. Briseno— kicked King and hit him with their batons more than fifty times while he struggled on the ground.

Unbeknownst to the officers, an amateur photographer, George Holliday, videotaped eighty-one seconds of the beating. The videotape was shown repeatedly on national television and became a symbol of complaints about police brutality.

The four officers were charged with numerous criminal counts, including assault with a deadly weapon, the use of excessive force, and filing a false police report. Because of the extensive publicity surrounding the case, the trial of the four police officers was conducted in Simi Valley, a predominantly white community located in Ventura County, not far from Los Angeles. During the trial the prosecution used the videotape as its principal source of evidence and did not have King testify. The defence also used the videotape, examining it frame by frame to bolster its contention that King was resisting arrest and that the violence was necessary to subdue him. The defence also contended that the videotape distorted the events of that night, because it did not capture what happened before and after the eighty-one seconds of tape recording.

On April 29, 1992, the jury, which included ten whites, one Filipino American, and one Hispanic, but no African Americans, found the four police officers not guilty on ten of the eleven counts and could not come to an agreement on the other count. The acquittals stunned many persons who had seen the videotape. Within two hours riots erupted in the predominantly black South Central section of Los Angeles. The riots lasted seventy hours, leaving 60 people dead, more than 2,100 people injured, and between $800 million and $1 billion in damage in Los Angeles. Order was restored through the combined efforts of the police, more than ten thousand National Guard troops, and thirty-five hundred Army and Marine Corps troops.

In the riot’s aftermath, criticism of the Los Angeles police, which had escalated after the King beating, grew stronger. Many believed that the longtime police chief, Daryl F. Gates, had not sufficiently prepared for the possibility of civil unrest and had made poor decisions in the first hours of the riots. These criticisms, coupled with the determination by an independent commission headed by Warren G. Christopher (a distinguished attorney who served in the State Department during the administration of President Jimmy Carter) that Gates should be replaced because of the brutality charges, placed increasing pressure on the police chief. Gates finally resigned in late June 1992.

In August 1992 a federal grand jury indicted the four officers for violating King’s civil rights. Koon was charged with depriving King of due process of law by failing to restrain the other officers. The other three officers were charged with violating King’s right against unreasonable search and seizure because they had used unreasonable force during the arrest.

At the federal trial, which was held in Los Angeles, the jury was more racially diverse than the one at Simi Valley: two jury members were black, one was Hispanic, and the rest were white. This time King testified about the beating and charged that the officers had used racial epithets. Observers agreed that he was an effective witness. The videotape again was the central piece of evidence for both sides. On April 17, 1993, the jury convicted officers Koon and Powell of violating King’s civil rights but acquitted Wind and Briseno. Koon and Powell were sentenced to two and a half years in prison.

King filed a civil lawsuit against the police officers and the city of Los Angeles. After settlement talks broke down, the case went to trial in early 1994. On April 19, 1994, the jury awarded King $3.8 million in compensatory damages. However, the jury refused to award King punitive damages. In July 1994 the city of Los Angeles struck a deal whereby King agreed to drop any plans to appeal the jury’s verdict on punitive damages. In return, the city of Los Angeles agreed to expedite payment of King’s compensatory damages.

False Imprisonment

False imprisonment may sound like a person being dangerously restrained against their will and at risk of being seriously injured or killed. In a way, it is, but also can describe other situations which aren’t so very dangerous sounding. The definition of false imprisonment is the unlawful restraint of someone which affects the person’s freedom of movement. Both the threat of being physically restrained and actually being physically restrained are false imprisonment. In a facility setting, such as a nursing home or a hospital, not allowing someone to leave the building is also false imprisonment. If someone wrongfully prevents someone else from leaving a room, a vehicle, or a building when that person wants to leave, this is false imprisonment. This can apply to family members if the person desiring to leave is an adult. Years ago when “deprogramming” was in style, several parents and family members were prosecuted for false imprisonment for confining adult children. Spouses have no legal right to confine each other either.

False imprisonment; the word ‘false’ means ‘erroneous’ or ‘wrong’. It is a tort of strict liability and the plaintiff has not to prove fault on the part of the defendant. To constitute this wrong, two things are necessary. 1. The total restraint of the liberty of a person. The detention of the person may be either (a) actual, that is, physical, e.g. laying hands upon a person; or (b) constructive, that is, by mere show of authority, e.g. by any officer telling anyone that he is wanted and making him accompany. 2. The detention must be unlawful. The period for which the detention continues is immaterial. But it must not be lawful. “Every confinement of the person is an imprisonment, whether it is in a common prison, or in a private house, or in the stocks, or even by forcibly detaining one in the public streets.

To recover damages for false imprisonment, an individual must be confined to a substantial degree, with her or his freedom of movement totally restrained. Interfering with or obstructing an individual’s freedom to go where she or he wishes does not constitute false imprisonment. For example, if Bob enters a room, and Anne prevents him from leaving through one exit but does not prevent him from leaving the way he came in, Bob has not been falsely imprisoned. An accidental or inadvertent confinement, such as when someone is mistakenly locked in a room, also does not constitute false imprisonment; the individual who caused the confinement must have intended the restraint.

False imprisonment often involves the use of physical force, but such force is not required. The threat of force or arrest, or a belief on the part of the person being restrained that force will be used, is sufficient. The restraint can also be imposed by physical barriers or through unreasonable duress imposed on the person being restrained. For example, suppose a shopper is in a room with a security guard, who is questioning her about items she may have taken from the store. If the guard makes statements leading the shopper to believe that she could face arrest if she attempts to leave, the shopper may have a reasonable belief that she is being restrained from leaving, even if no actual force or physical barriers are being used to restrain her. The shopper, depending on the other facts of the case, may therefore have a claim for false imprisonment. False imprisonment has thus sometimes been found in situations where a storekeeper detained an individual to investigate whether the individual shoplifted merchandise. Owing to increasing concerns over shoplifting, many states have adopted laws that allow store personnel to detain a customer suspected of shoplifting for the purpose of investigating the situation. California law, for example, provides that “[a] merchant may detain a person for a reasonable time for the purpose of conducting an investigation … whenever the merchant has probable cause to believe the person … is attempting to unlawfully take or has unlawfully taken merchandise” (Cal. Penal Code § 490.5 [West 1996]).

False arrest is a type of false imprisonment in which the individual being held mistakenly believes that the individual restraining him or her possesses the legal authority to do so. A law enforcement officer will not be liable for false arrest where he or she has probable cause for an arrest. The arresting officer bears the burden of showing that his or her actions were supported by probable cause. Probable cause exists when the facts and the circumstances known by the officer at the time of arrest lead the officer to reasonably believe that a crime has been committed and that the person arrested committed the crime. Thus, suppose that a police officer has learned that a man in his forties with a red beard and a baseball cap has stolen a car. The officer sees a man matching this description on the street and detains him for questioning about the theft. The officer will not be liable for false arrest, even if it is later determined that the man she stopped did not steal the car, since she had probable cause to detain him.

An individual alleging false imprisonment may sue for damages for the interference with her or his right to move freely. An individual who has suffered no actual damages as a result of an illegal confinement may be awarded nominal damages in recognition of the invasion of rights caused by the defendant’s wrongful conduct. A plaintiff who has suffered injuries and can offer proof of them can be compensated for physical injuries, mental suffering, loss of earnings, and attorneys’ fees. If the confinement involved malice or extreme or needless violence, a plaintiff may also be awarded Punitive Damages. False imprisonment may constitute a criminal offense in most jurisdictions, with the law providing that a fine or imprisonment, or both, be imposed upon conviction

An individual whose conduct constitutes the tort of false imprisonment might also be charged with committing the crime of kidnapping, since the same pattern of conduct may provide grounds for both. However, kidnapping may require that other facts be shown, such as the removal of the victim from one place to another.

Important Cases Relating To False Imprisonment

Bird v. Jones, 7 Ad. & El. (N.S.) 742, 115 Eng. Rep 688 (1845)

In August 1843 the Hammersmith Bridge Company cordoned off part of their bridge, placed seats on it, and charged spectators for viewing a regatta. The claimant objected to this and forced his way into the enclosure, where he was stopped by two police officers, one being Jones. He was prevented from proceeding across the bridge because he had not paid the admission fee, but was allowed to go back the way he came. He refused, and in the course of proceedings for his arrest the question arose whether he had been imprisoned on the bridge.

Held: this was not an ‘imprisonment’ and the defendant was not liable for the subsequent arrest.

Bhim Singh vs. Jammu and Kashmir

This case deals with the issue of illegally detaining an MLA by the name of Bhim Singh by the police authorities in the state of Jammu and Kashmir. As per the facts of the case, the former had been suspended from the J&K Assembly on August 17, 1985 and had questioned the same in the High Court of the state, which stayed the suspension in September. He was on his way to Srinagar from Jammu on the intervening night of September 9-10, 1985. He was arrested on his way by the police authorities and was taken away.

The wife of Bhim Singh filed the application for the issue of the writ to direct his release besides declaring his detention as illegal. On being released on bail, Mr. Singh filed an affidavit in which he added many more facts. In the same he stated that he was kept in the police lock-up from the 10th to the 14th of September and was produced before the Magistrate for the first time only on the 14th.

The affidavits filed by the police officers dealt with many other facts than those relevant. The court took notice of the fact that the affidavits mentioned the facts in a way that the procedure for obtaining the remand orders from the Executive Magistrate First Class and Sub-judge. The remand orders were obtained, as was deciphered from the facts, without presenting the Mr. Singh before them. Further, the applications for remand didn’t contain any statement that Mr. Singh was being produced before the Magistrate or the Sub-judge. The manner of exercise of power of the judges was string suspect and the courts pointed out this very aspect.

The remand orders were first obtained from the Executive Magistrate and then, from the Sub-Judge even without the production of the accused before them just on the basis of the applications of the police officers. The former also passed the remand orders without the slightest hesitation with regard to the aspect that the person, who they were remanding, had not been produced before them at all. From the above it was very clear that the acts of the police were mala fide and that of the two other officers was irresponsible, if not anything else. The important aspect that the courts looked into in the present case was that of compensation to the victim for the wrong that he had to encumber.

Here, the Supreme Court ruled that the present case is apt for consideration of compensation in lieu of the damage done to the person. A compensation of Rs 50, 000/- was awarded to Mr. Singh It also further opined that the case for compensation should arise only in exemplary cases where the aspect of mala fide intentions and reckless and arbitrary exercise of power is evident; such a situation being present, the Supreme Court opted for compensation in the present case. As per the judgment of the Supreme Court, when a person comes with a complaint of having been arrested and imprisoned with mischievous intent or malice and in the process of which his Constitutional or legal rights are violated, then the same act of depriving him of his rights will not be without consequences. And in pursuance of the same, the Supreme Court is within its jurisdiction to award monetary compensation.

Enright v. Groves, Colorado Court of Appeals, 1977. 39 Colo.App. 39, 560 P.2d 851. Prosser, 43-45.

The defendant, a police officer, was enforcing a dog leash ordinance and approached the plaintiff in her car. He demanded her driver’s license several times, but she refused. Groves threatened to arrest her if she didn’t produce her license, but Enright did not comply. Groves forcibly took her into custody and filed a complaint against her for the dog leash violation, for which she was later convicted. Enright sued for false imprisonment and won damages in the trial court. The defendant appealed on the basis that he had probable cause to arrest Enright, since she was later convicted.

The court reasons that the officer did not have proper legal authority because there he evidence he did not arrest Groves for the dog leash violation, but rather for failing to produce her driver’s license. The court affirmed the judgment of the trial court.

If the defendant is not an officer, it would make false imprisonment even more likely to lie. In the case of the filling station attendant, there is apparently no proper legal authority, so if the plaintiff is held against their will, it would be false imprisonment. In the latter case, it would make a difference whether the defendant accurately stated the law. When you have a broken leg, it would seem that denying you a means of transportation physically prevents you from moving, so false imprisonment makes sense.

The Boy George Case

Former Culture Club frontman Boy George was sentenced to 15 months in jail after being found guilty of falsely imprisoning Norwegian male escort Audun Carlsen, whom he met over the Internet. Tried under his real name George O’Dowd, the 47-year-old Briton denied a charge of false imprisonment at his London flat in April, 2007.

After the jury ruled against him, Judge David Radford had warned him that he faced a prison term. However, the length of the sentence was a surprise as lawyers had expected a jail term of around three months. “This offence is so serious that only an immediate sentence of imprisonment can be justified for it,“ Radford said. “Taking into account the aggravating and such mitigating factors as there are, the sentence of the court is one of 15 months imprisonment.“

O’Dowd remained calm as he stood in the dock, but the verdict clearly shocked friends and family, some of whom burst into tears. he singer had told police he had invited Carlsen back to his home after a cocaine-fuelled pornographic photo shoot in January, 2007, because he suspected the Norwegian of stealing pictures from his computer.

During the two-week trial, Carlsen countered that the singer had handcuffed him to a wall and beaten him with a chain because he was angry he had refused to sleep with him when they first met. O’Dowd did not give evidence during the trial. Snaresbrook Court in east London heard Carlsen describe how he sustained injuries during their meeting in April, 2007, from being beaten and handcuffed. O’Dowd’s lawyer said the injuries were consistent with bondage gear the Norwegian had worn.

False Imprisonment And The Constitution Of India

The Constitution of India envisages certain provisions exclusive to the interests of the individuals especially with regard to their personal freedom and infringement on it. The mandate of the Constitution awards gravity to the entire spectre of rights relating to an individual’s personal freedom. It is under this ambit that the aspect of false imprisonment can be located.

Right to life and personal liberty read through the Article 21 into the Constitution of India is a crucial provision. The intention is to protect the life and liberty of the people from the wishful acts of the Executive. The imprisonment of a person cannot be ordered by anyone in the position of power and authority to do so if there is no law providing for the same. Article 22 derives basically from the principles of the Article 21 and deals specifically with the aspect of manner of arrest and imprisonment. While the latter says that, “No person shall be deprived of his life or liberty except by procedure established by law.” The former Article says that a person who is arrested should be informed regarding the grounds of his arrest. At the same time, he should be permitted to seek the services of his lawyer. And he should be produced before the nearest magistrate within 24 hours of his arrest. An indirect echo of the above rights is also observed in the Article 20, which provides for protection against ex-post-facto laws and double jeopardy.

In case of violation of any of these rights, a citizen of India is free to move to

The Supreme Court or the High Court under the writ petitions (Article 32 and Article 226 respectively). Such petitions may be moved under the heads of certiorari, quo-warranto and prohibition. The only exceptions to the above Fundamental Rights arise with regard to the defence and security concerns of the nation. The Rudul Shah case assumes special significance in this discussion on state liability for false imprisonment. In the present case the Supreme Court ordered the award of compensation of Rs. 35, 000/- apart from the release of the person who had been illegally detained for a period of 14 years. This was a landmark as it was the first instance of the Supreme Court linked the constitutional provision of Habeas Corpus with the principle of compensation.

Besides, as is the standard practice, any law in contravention to the

Fundamental Rights guaranteed under the Constitution of India stands void; therefore, any legislation by the State or Union Legislatures running in contradiction to the above Fundamental Rights with regard to personal liberty shall stand void. The right to freedom of personal liberty has certain defences against it, which is basically envisaged keeping in mind the need of the public authorities to act in the interest of public law and order in particular and the security of the nation in general.

The judiciary is shielded from the consequences of their actions vide the Judicial Officers Protection Act, 1850. This protection is available basically against the judgments passed by the judges or in the exercise of their judicial powers in any other manner. However, the above act is not without its own limitations such that in character and function it doesn’t become absolute.

It is clearly observed that the standards laid down by the Supreme Court are strict when it comes to safeguarding citizens against the malice of false imprisonment.

To quote:

“No arrest should be made without a reasonable satisfaction reached after some investigation into the genuineness and bonafides of a complaint and reasonable belief as to the person’s complicity and even so as to need to effect arrest, arrest must be avoided if a police officer issues a notice to the person to attend the station house and not to leave station without permission to do so.” The remedy available under the Constitution is the writ of Habeas Corpus, which is available not just against any government authority but also against any other instance of unlawful detention. In the words of Dr. BR Ambedkar: “If I was asked to name any particular article in this constitution as the most important -an article without which this Constitution would be a nullity- I could not refer to any other article except this one. It is the very soul of the Constitution and the very heart of it.”

Executive authorities have to be within the limits prescribed to them by the Constitution or other legislative enactments while exercising their duties. Failing which the authorities invite the prospect of false imprisonment. While the conventional statutes like the CrPC. 1898 deal with the regular instances of crime, with regard to special statutes like the National Security Act, 1980, the limitations to regulate the powers are laid in the statute itself.

Defences To Trespass To Person

Consent

If the plaintiff gives consent to the action, that may be a defence for the defendant. However, the consent must be real. That is, it must be an informed consent, the person must give it voluntarily, consent must be genuine and the defendant must have acted in a way which remained within the scope of the consent which the plaintiff actually gave.

However, the person does not need to explicitly state the consent in order for the consent to be effective. It may be possible to imply that consent from the circumstances in which the persons are involved. E.g., sports people, the kinds of behaviour which a sports player consents to will differ depending on the nature of the sport. By participating in karate, judo, kick boxing and boxing, people by implication consent to contact and aggression as an integral part of the sport. Compared with players of other contact sports such as rugby, they may consent to more contact or perhaps a different form of contact and threatening behaviour. Even so, rules still define legitimate contact and the acceptable occasions for making it, and these rules are relevant in determining the scope of the consent. For example, suppose a person is limbering up in a karate class before the contest has begun. One of the other class members comes up behind her and kicks her. That is battery. A second example is where a person willingly undergoes operative surgery, and thus consents to surgical procedures which might be battery without that consent. But note that the important issue in this context is the scope of what is consented to. Consent to one form of operative procedure does not license the surgeon to carry out any operative procedure.

Superior Lawful Authority

Certain persons have legal authority to exercise force and to threaten the use of force on other persons. Usually such authority is granted for the purposes of public peace and order. Police officers, and citizens under certain circumstances, have authority to exercise force against others. Hotel owners are entitled to eject people from their premises under certain conditions. If owners or proper occupiers of land are faced with a trespasser, they can use reasonable force to eject the trespasser from the land under certain conditions. The law has also often held that parents have legitimate authority to apply force against children to discipline them. It also extended such authority to persons in loco parentis (i.e. who stand “in the place of parents”) such as guardians and school teachers. But in many jurisdictions today, neither parents nor persons in loco parentis have such authority.

Mistake

Unavoidable mistake (accident) can amount to a defence when the mistake negates the required element of intention—or, in other words, when the person did not intend the consequences of his or her act. So, for example, a person had no intention of coming into contact with another person but accidentally did so, then there is no battery. Say a police officer mistakenly believes that a felony has been committed and the officer arrests a person whom he/she reasonably believes to have committed the felony. The mistake would excuse the officer from battery or false imprisonment. This was decided in Beckwith v Philby (1827) 6 B & C 635; 108 ER 585.

However, it is no defence to say that the intended consequences of the act were somehow innocent or had a legal effect that was different from the effect which the defendant assumed. For example, suppose a shopkeeper strikes a child on the assumption that the act is within her lawful authority. The shopkeeper clearly intended the consequences but she is mistaken about the legal effect of the act and her legal right to do it. She did not intend to do something that was unlawful perhaps. But that sort of mistake is no defence to battery or assault or, indeed, to any form of trespass. Or suppose that a police officer has a valid arrest warrant but arrests the wrong person. The mistake will be no defence because the officer actually intended to apprehend the person in question.

Unfortunately the position is rather confused because of the seemingly artificial distinctions between mistake and accident. Unavoidable mistakes often appear as innocent as do the production of accidental (unintended) results. Hence whilst the distinction still appears as a result of the historical development of tort it often appears to have little justification as a matter of policy.

Self-Defence

If a person uses legitimate force to repel an attack either against himself or others or against his property, that is a defence to assault and battery. The action of self-defence must only be such as is appropriate to repel the attack; it must not be excessive. If an attacker is unarmed, it would be excessive action to repel the attack by shooting him or her. It would also be unreasonable and excessive to kick an attacker after you have knocked him or her unconscious.

Necessity

Suppose that it is necessary to apply force to another person in order to save that person’s life. For example, a lifeguard might have to knock out a swimmer who is in danger, in order to be able to bring the swimmer back to shore. Necessity would be a defence in such cases. Of course, in many cases there is a fine line between necessary action and assault or battery. For example, in emergency surgical procedures the answer might depend on whether the emergency was real. In a case where the patient’s life would be immediately threatened if the surgeon did not carry out the procedure, then the necessity for action overrides any other requirement of consent. But suppose that the patient’s life is not in immediate danger, and the surgeon could have finished the current procedure and then sought the consent of the patient, thereby postponing the operation until shortly afterwards. In those circumstances, if the surgeon still performs the additional procedure without consent, perhaps because it is convenient to herself or to her employers, then those actions are not a matter of necessity and so necessity cannot be a defence.

Necessity might apply in cases where it relates to a need to defend your own interests or your own health, just as it might apply with respect to the need to protect the interests of others. In such cases, there is clearly an overlap with the defence of self-defence.

Conclusion

I would like to conclude by stating the reason for selecting this topic. The reason I chose this topic is because I feel this is a very common tort that takes place in day-to-day life of the people, especially labourers and hence, there is a need to make the people aware of this tort and seek justice. The tort of false imprisonment is one of the most severe forms of human rights violations especially in a nation like India that holds the writ of Habeas Corpus as the “heart and soul” of its Constitution. The assault and battery cases need to be taken more seriously by the courts and should be given a speedy judgement. Since the people have a psyche of the courts taking long time to give a judgement, they prefer to chuck the assault or battery that they suffered from and thus, don’t initiate to file a case. Appropriate compensation has to be given to the damages the claimant faced.